Strange Darling

By Brian Eggert |

Note: This review was originally posted on August 5. Magenta Light Studios will release Strange Darling in theaters on August 23, 2024.

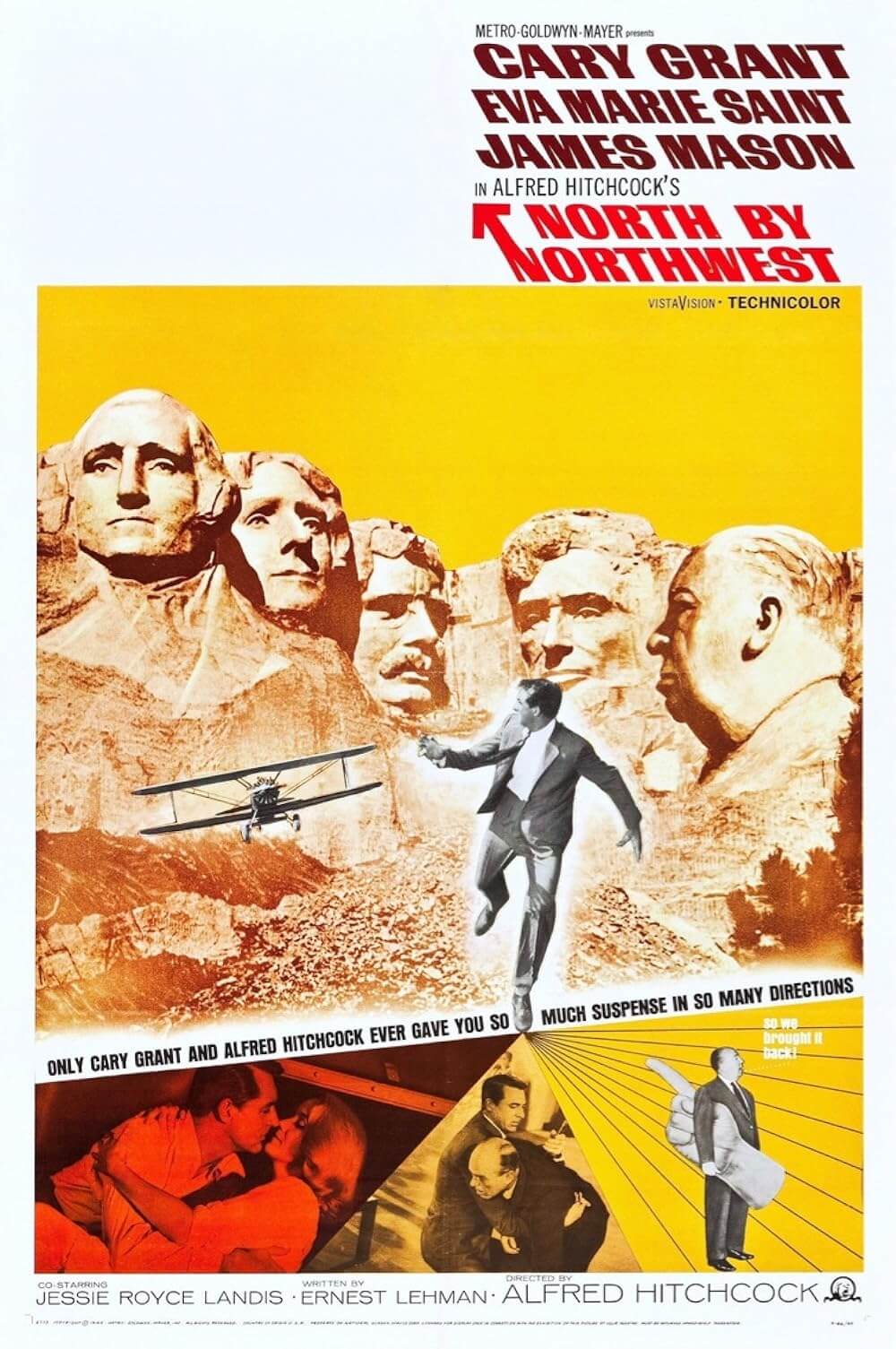

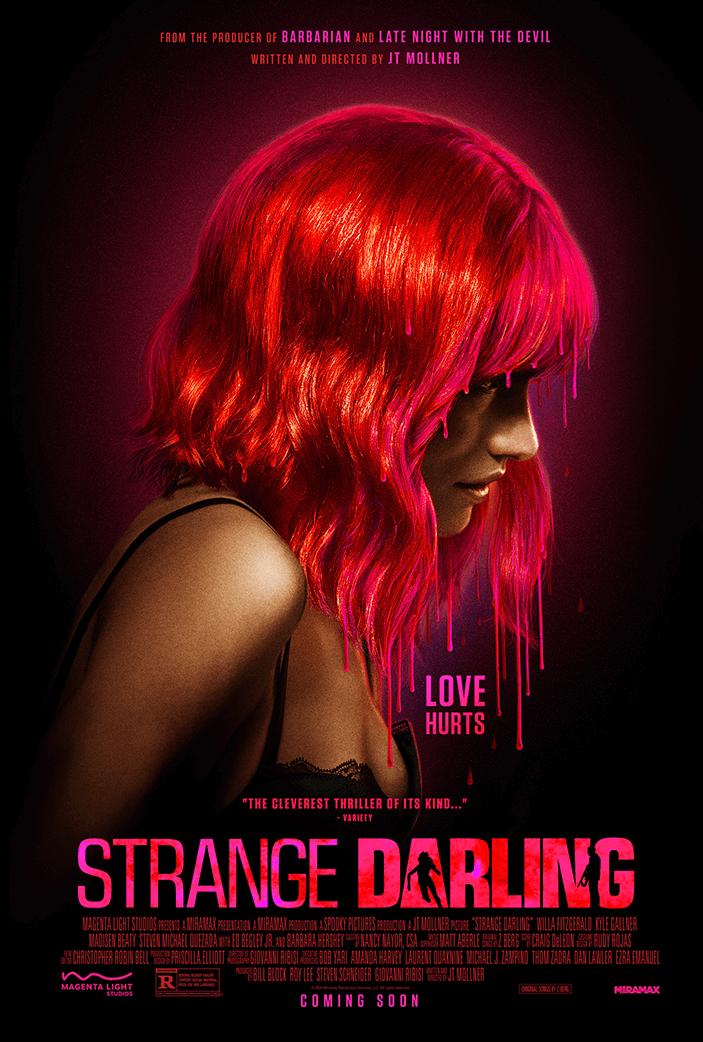

Few images have more cinematic antecedents than a blonde woman in distress. From the silent era to Alfred Hitchcock to decades of slasher movies, blondes have been symbols of innocence in peril in films for over a century. The motif stems from Arthurian legend and fairy tales about noble heroes who set out to rescue a fair-haired maiden from danger. Strange Darling opens with imagery that exploits this stereotype. Set against a melancholy cover of Nazareth’s “Love Hurts” by singer Z Berg, the film shows a bloodied young woman with bleached hair running for her life through a field. The opening credits play into the film’s game, labeling the leads as archetypes: The Lady (Willa Fitzgerald) and The Demon (Kyle Gallner). However, JT Mollner’s film, his second as writer-director, has more on its mind than reinforcing conventions. Here’s a taut, keeps-you-on-your-toes thriller that sets the viewer’s preconceptions like a trap. And while Mollner toying with the audience’s expectations is unquestionably manipulative, at times transparently so, he also delivers an impeccably crafted nail-biter that’s skillfully shot and bound to prompt a potent response.

Mollner doesn’t shy away from his obvious sources. Strange Darling is a pastiche of stylistic choices, nonlinear narrative structures, and details culled from memorable works by famed directors. The opening scrawl and voiceover recall those in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), establishing “a dramatization of the true story” about “the most prolific and unique American serial killer of the 21st century.” From here, an ensuing car chase in pastoral Oregon recalls those in Quentin Tarantino’s Death Proof (2007). On a broader scale, the film’s non-chronological chapter structure borrows a tactic from Pulp Fiction (1994), with hints of Lars von Trier’s The House That Jack Built (2019) in its fastidious organization of discontinuous segments. To whatever degree Mollner wears his influences on his sleeve, he keeps our attention on the story with his effective plotting and killer twists. The less you know, the better, so consider this a recommendation. With that in mind, beware of spoiler-y allusions throughout the rest of this review.

Though announced as “A Thriller in 6 Chapters” under the title, Strange Darling opens with Chapter 3. Gallner appears in a mustache, wearing a red plaid flannel shirt-jacket and work boots. He drives a black pickup truck that pursues an old Pinto with Fitzgerald behind the wheel. She appears desperate and missing an ear, apparently having survived an unimaginable ordeal. Based on appearances, the viewer instantly understands the setup. We follow the desperate woman as she finds refuge at an isolated farm owned by two bizarrely eccentric hippies (Ed Begley Jr. and Barbara Hershey), who blare the sounds of fringe radio on their property. But then, jumping to earlier chapters, Mollner’s sharp screenplay finds the combating leads on a date, parked outside a hotel, with a neon sign showing them in blue hues. “Do you have any idea the risks a woman like me takes whenever she decides to have a little fun?” she asks him. Both want casual sex, but first, she has a question: “Are you a serial killer?”—as though killers were bound by the same disclosure laws that govern undercover police officers. He is not a serial killer, or so he claims.

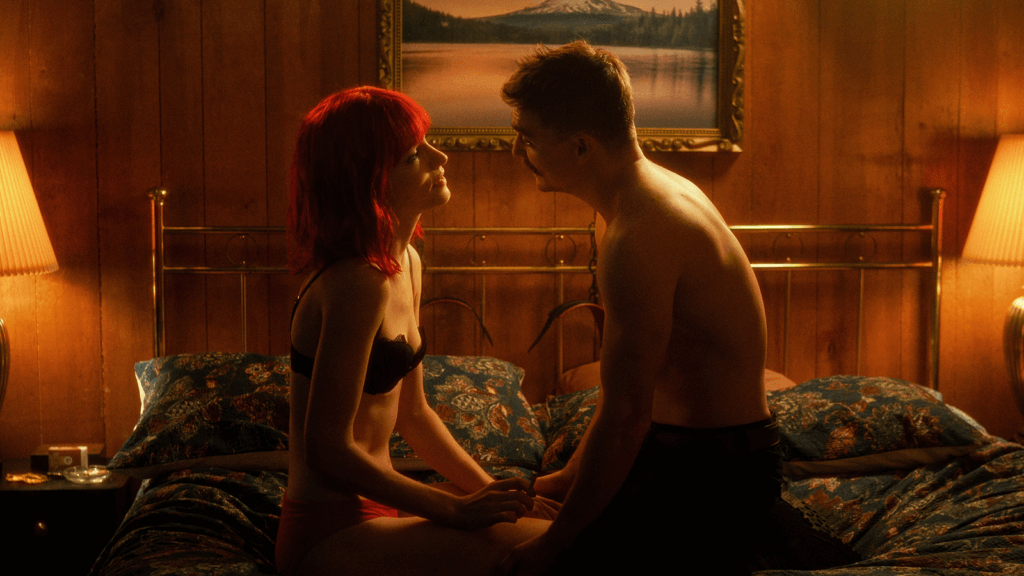

Mollner constantly plays with our assumptions about and dread over the situation, often weaponizing today’s gender politics against the audience, sometimes in clever ways, sometimes with blatant provocations. Cut to inside the hotel room, where Gallner’s character appears to be choking out Fitzgerald. “You know you asked for this,” he says in a disturbing, if common line. Then the other shoe drops: “Harder,” she asks. She did literally ask for this. She even tells him, “No means yes,” and declares, “I could not imagine consent being any more clear.” But to what end? The material will test some viewers’ limits; even if the sadomasochism on display amounts to role-playing, it’s not presented as such initially. Mollner’s screenplay is filled with confronting details that upend serial killer genre gender roles, destabilizing the viewer’s understanding of predator and prey in this dynamic. And while the reordered chapters might seem like a post-Tarantino gimmick initially, their arrangement conceals crucial information and strategically positions story details to turn the entire scenario on its head to surprising effect later.

Mollner constantly plays with our assumptions about and dread over the situation, often weaponizing today’s gender politics against the audience, sometimes in clever ways, sometimes with blatant provocations. Cut to inside the hotel room, where Gallner’s character appears to be choking out Fitzgerald. “You know you asked for this,” he says in a disturbing, if common line. Then the other shoe drops: “Harder,” she asks. She did literally ask for this. She even tells him, “No means yes,” and declares, “I could not imagine consent being any more clear.” But to what end? The material will test some viewers’ limits; even if the sadomasochism on display amounts to role-playing, it’s not presented as such initially. Mollner’s screenplay is filled with confronting details that upend serial killer genre gender roles, destabilizing the viewer’s understanding of predator and prey in this dynamic. And while the reordered chapters might seem like a post-Tarantino gimmick initially, their arrangement conceals crucial information and strategically positions story details to turn the entire scenario on its head to surprising effect later.

Plenty of curious details occur, particularly with the hippie characters who woof down an absurd breakfast—Begely Jr.’s character prepares food like a 4-year-old would—before working on a Scott Baio puzzle. Stranger still is the credited cinematographer, Giovanni Ribisi, a longtime actor who shows that he’s been paying attention behind the scenes. Before the opening titles, Strange Darling proudly announces, “Shot entirely on 35mm,” and there’s good reason for such pride. Ribisi employs lighting that evokes the work of Robert Richardson (JFK, 1991) and camera movements worthy of Michael Ballhaus (After Hours, 1985). The film boasts rich colors, with a particular affinity for reds (Fitzgerald’s shoes and nurse scrubs, Gallner’s flannel, everyone’s blood) and greens (showcasing the Oregon exteriors). It’s a heightened visual treatment with expressive tricks, such as split-diopter lensing and fade-outs to primary colors. Editor Christopher Robin Bell allows these visuals to flourish with a longer-than-average shot length, both patient and assured. Such bold choices are contrasted by the slow, gentle songs performed by Z Berg and more aligned with Craig DeLeon’s jarring score—music with reverberating grandiosity, discordant sounds, and booming guitar riffs.

Strange Darling can sometimes feel more interested in plot machinations and twists than in developing dimensional characters. Still, it’s all very engrossing. Gallner adds presence to his role, whereas Fitzgerald gives a sublime performance and, only toward the end, begins to reveal the forces compelling her. Neither The Lady nor The Demon receives much background, but that’s in service of its plot mechanics and disorienting shocks—some of which involve a nasty streak of violence and aggression against women; though, that resourcefully feeds into the film’s agenda, enough to feel like a critique of the behavior it depicts. So buckle in, and let Mollner take you for a ride into juicy, exploitative situations that might register as hackneyed in another filmmaker’s hands. Instead, Mollner leverages what we’ve been reinforced to think based on centuries of storytelling, and then he flips the script with unsettling results. It’s all rendered into an even more enjoyable surprise, given Ribisi’s top-notch camerawork. Everyone involved is evidently having fun rethinking genre tropes for audiences well-versed in thrillers, ready to pounce on those who might enter Strange Darling with their minds already convinced of what they’re about to see.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review