Stoker

By Brian Eggert |

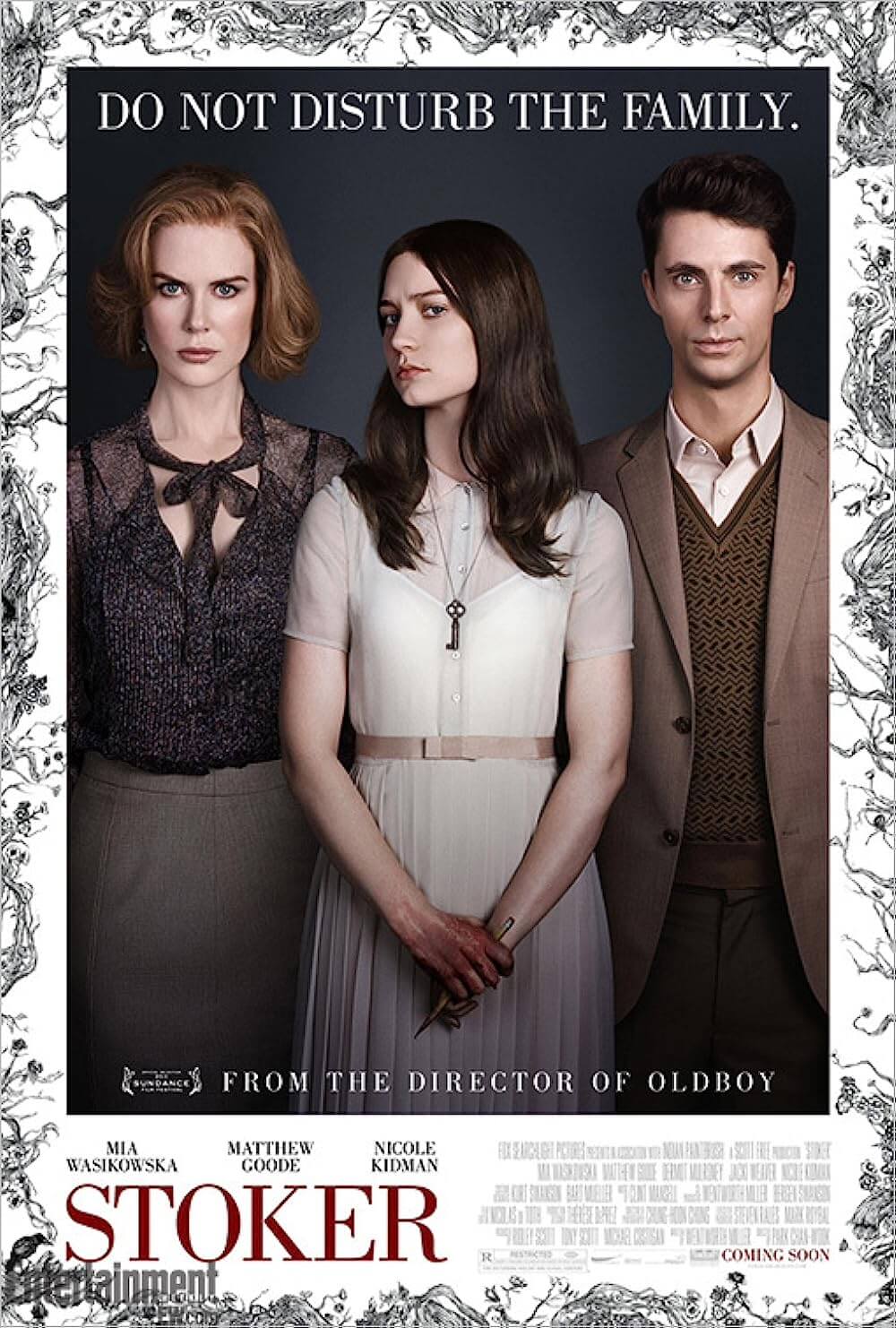

In Stoker, South Korean director Park Chan-wook floods our senses with aural and visual information. From the crackling of a hard-boiled egg on a kitchen table to the whispers of funeral attendees in the next room, Mia Wasikowska’s India Stoker hears and sees things others cannot, and so we do too. After her father dies on her eighteenth birthday, India hears someone at the funeral talking to her from afar, a man standing on the nearby hill and watching the service at the gravesite. She learns later this is her Uncle Charlie (Matthew Goode), a charismatic and mysterious figure she never knew existed, as he’s supposedly been traveling abroad for the entire span of her life. India’s unstable mother (Nicole Kidman) clings to Charlie in her grief, but he seems to only have eyes for India. Borderline incestuous connections between a niece and so-named Uncle Charlie cannot help but recall Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (1943), the obvious inspiration here where a niece suspects her visiting uncle to be a murderer. But in Park’s hands everything in the subtext of Hitchcock’s film, and then some, comes spiraling out into the narrative foreground.

The first English-language film from the Oldboy auteur, Stoker contains many nods to the works of Hitchcock. India herself feels inspired not only by Teresa Wright’s original niece “Young Charlie” from Shadow of a Doubt, but also by Psycho’s Norman Bates (and perhaps even a little from Michael C. Hall’s titular character in Showtime’s Dexter). She is a puzzling loner type who’s at once morbid and undoubtedly brilliant. When she’s not reading an encyclopedia of funeral practices, she is fondly remembering her hunting trips with her departed father (Dermont Mulroney), the spoils of which have been taxidermied and displayed in a creepy fashion about the Stoker home. And what a home, so lavishly decorated in an elegant country house way, natural yet almost sterilized to lend the surroundings the sense that no one is actually living there. Park’s recurrent cinematographer Chung Chung-hoon shoots the house and its inhabitants with an off-putting intimacy comparable to the naturalized style of filmmaker Terrence Malick (The Tree of Life), but curiously repellent because Park has raised the question: What’s going on in that Stoker house?

Certainly Park’s last film, 2009’s vampire reinvention Thirst, comes to mind, as the name “Stoker” recalls Bram Stoker, the author of Dracula. This would be another nod to Shadow of a Doubt, actually, since Hitchcock also made the correlation between Uncle Charlie and Bram Stoker’s charismatic vampire. Goode’s Charlie has a vampire-like magnetism that incites Kidman’s cold mother character Evelyn to forgo any mourning and instead lust after her late husband’s brother. His bloodlust becomes evident early on too, when more than one character who threatens to interrupt his immersion into the Stoker household goes missing. Jacki Weaver appears as Charlie’s concerned aunt who desperately wants to speak with Evelyn or India alone, away from Uncle Charlie. This proposed conversation never takes place, and her subsequent disappearance might be Park’s roundabout nod to The Birds, her last appearance occurring in a phone booth. Charlie’s presence also excites something in India, who, after witnessing first-hand Charlie’s capacity for murder, masturbates in the shower in a scene both haunting and beautiful. Whereas Hitchcock’s film barely hinted at the attraction between Uncle Charlie and his niece, Park makes this element palpable within the subtext.

Sex and violence, and even incest, have a curiously meaningful place in Park’s body of work, which seems comprised entirely of projects too radical or risqué for Hollywood sensibilities. How odd then that Park has somehow brought his completely unique and visceral work stateside in 2013 in more ways than just Stoker (Spike Lee is currently in production on a remake of Oldboy, which is due to reach theaters in fall 2013, but his film will no doubt subdue the potency of Park’s original). For all its strangeness and macabre subject manner, Stoker feels somewhat muted for a film by Park Chan-wook as well, which is to say it’s stranger and more thematically graphic than any other motion picture in theaters right now, but nevertheless represents a muted version of Park’s brand of storytelling. Rather than a primeval tale like his “Vengeance Trilogy” (including Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance, Oldboy, and Lady Vengeance) or even his under-seen I’m a Cyborg, But That’s OK, this film is almost an exercise in pure style.

Park has split off from his usual approach to engage in a kind of visual poetry in Stoker, where story sometimes becomes less important to the scene than the pristine quality of the image. Colors are rich and vibrant, and each shot bears a quality of perfection, suggesting Park has labored over the composition and layout of every given frame. At times we question if this or that sequence really happened, or if perhaps it takes place in India’s head, or maybe Charlie’s. Along with editor Nicolas De Toth, Park creates whole sequences that cut back and forth between India and Charlie to imply their connection and unspoken relationship, but in ways that play out almost like a David Lynch film, with certain imagery such as a rocking overhead lamp or spider crawling up India’s leg repeated for effect—repeated, but never just a recycling of the same shot over and over. To watch Stoker is to subject oneself to a fascinating inflow of visual stimulus, while the story becomes nearly secondary yet remains crucial to mull over both during and afterward.

With her performances in both Jane Eyre and The Kids Are All Right, and through her pensive and internal performance here, Wasikowska once again proves she’s better than her big-time debut in Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland. Along with Wasikowska’s costars, particularly the devilish Goode and intense Kidman, this ensemble delivers some of the strangest and most compelling performances in recent memory, conceived, surprisingly, by first-time screenwriter Wentworth Miller (star of TV’s Prison Break). Directing a stellar cast of performers who clearly enjoyed sinking their teeth into these juicy, sordid roles, Park proves his talent is beyond borders. Stoker is an impressive first project in a language other than his first, even if the Hollywood influence is felt in the off-putting, far-too-hip song that blares during the last shots and over the end credits, spoiling the anticeptic horror mood. The film is the product of a filmmaker demonstrating his appreciation for the genre and craft in which he’s working, but he also incorporates his own touches to make Stoker a unique pleasure of disturbing turns, complex and dangerous characters, and thoughtful direction teeming with style.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review