Steve Jobs

By Brian Eggert |

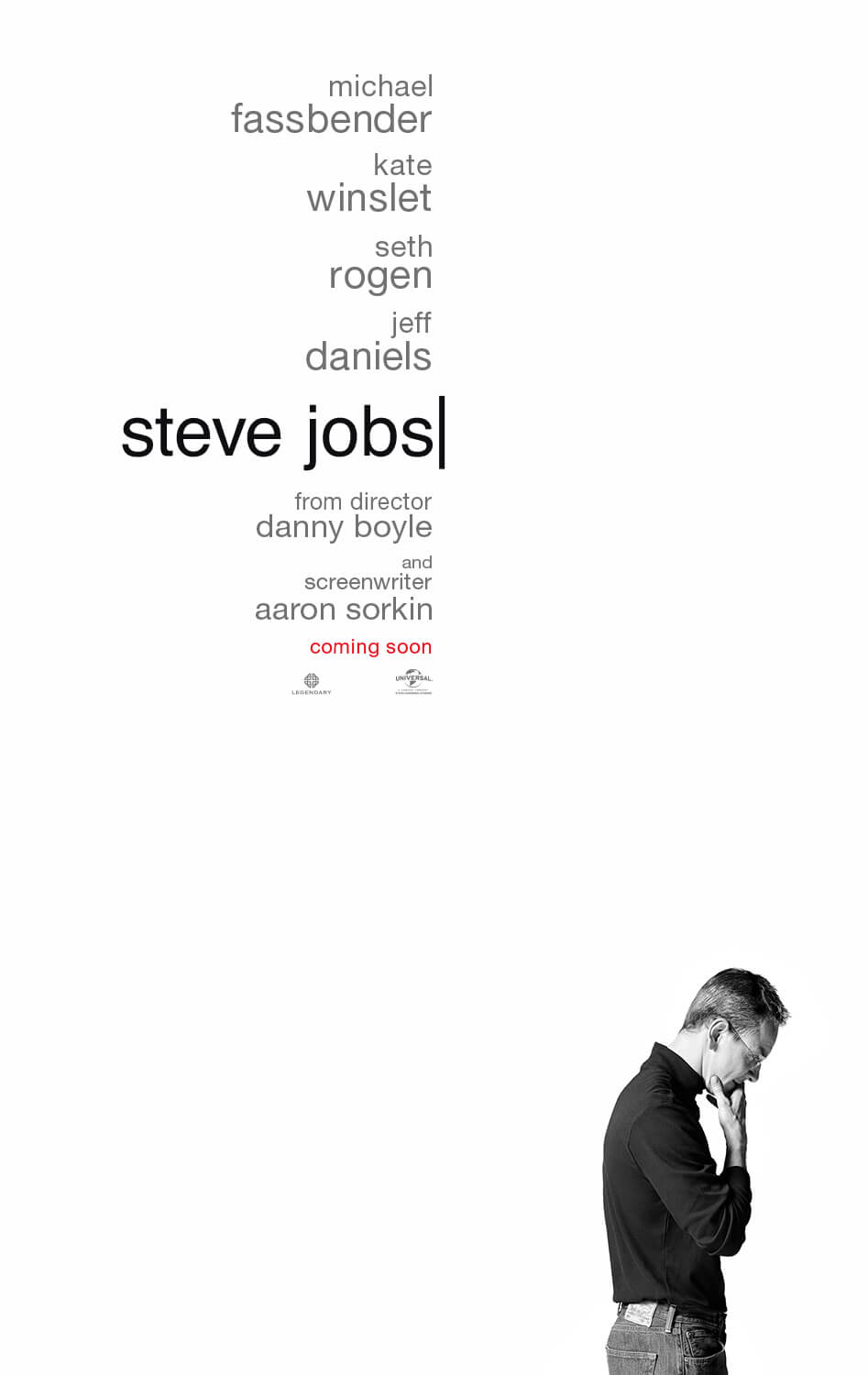

Danny Boyle could make watching grass grow or paint dry an energetic, meaningful, and stimulating experience. Not that his virtuoso effort on Steve Jobs deserves comparison to such tedium, as nothing about screenwriter Aaron Sorkin’s treatment of Apple’s late co-founder and CEO could be described as dull, despite taking place almost exclusively in a series of three backstage conversations prior to three central tech product launches. Much like Alejandro G. Iñárritu did on Birdman: Or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) from 2014, the film’s structural and formal dynamism by both Boyle and Sorkin shape into a radical, unconventional look at an enigmatic subject. Both the man and the highly mythologized visionary have layers stripped away throughout the picture, while the filmmakers simultaneously establish a newfound level of complexity around his personal and professional lives, granting their audience to pass whatever judgments they may with equal measures of admiration and criticism.

What a brilliantly made oddity is this, a film about a famous minimalist brought to life through the kinetic masterstrokes of two artists who conversely root their styles in expressive flourishes. Based on this strange juxtaposition of styles, you would think the resulting clash would be incompatible and even disastrous. One could imagine style trying to compensate for content and feeling incongruous. However, Boyle and Sorkin make a genius alliance, just as Sorkin and director David Fincher did on The Social Network (2009), about Facebook trendsetter Mark Zuckerberg. The association between bravado formal style and limited staging in Steve Jobs nonetheless buzzes with intensity, serving as a metaphor for the mysterious inner workings of the film’s titular figure. As it turns out, Boyle’s lively visuals and Sorkin’s acerbic rapid-fire dialogue ideally represent the controlling and chaotic temperament of their subject.

Steve Jobs was based on Walter Isaacson’s authorized 2011 biography of the same name, but Boyle and Sorkin are not the first filmmakers to bring Jobs’ life to the screen. In 1997, Noah Wyle played him in the TV movie Pirates of Silicon Valley. He was also the subject of a dull biopic called Jobs (2012) starring Ashton Kutcher alongside Josh Gad as Steve Wazniak. And just a month prior to Boyle’s film, Magnolia Pictures and director Alex Gibney released the probing documentary Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine. Regardless of how many films or books are (or will be) released about Jobs’ life, few will also happen to deliver such an alternative experience, and do it so entertainingly, as Steve Jobs. Employing standard Sorkin-isms such as the walk-and-talk, verbal sparring, and quips galore, Boyle’s film crackles along at the pace of an electric current, yet offers the most fascinating view of Jobs yet.

By association, Jobs’ degree of prophetic thinking is equated to that of another visionary, Arthur C. Clarke. Alongside the opening credits, the vintage black-and-white footage shows Clarke standing in a room of towering early computers, vowing that someday they will bring people closer together and enrich our culture. If Clarke predicted it, Jobs arguably made it happen. The film’s structure tracks Jobs at three major stops over the course of fifteen years, beginning in 1984, just after Ridley Scott’s monumental Orwellian commercial for the Macintosh personal computer debuted for the first (and last) time during the Superbowl. But rather than follow a progression of Jobs’ life with intimate, dramatized scenes encompassing significant events and relationships, Sorkin’s script breaks the action into three events: Jobs’ introduction of the Macintosh in Cupertino, California; his strategic unveiling of the NeXT Cube in 1988, five years after he was forced out of Apple; and then again in 1998, just after Jobs has regained control his former company to showcase the bestselling iMac—paving the way for iPods, iPhones, iPads, and countless other innovations.

By association, Jobs’ degree of prophetic thinking is equated to that of another visionary, Arthur C. Clarke. Alongside the opening credits, the vintage black-and-white footage shows Clarke standing in a room of towering early computers, vowing that someday they will bring people closer together and enrich our culture. If Clarke predicted it, Jobs arguably made it happen. The film’s structure tracks Jobs at three major stops over the course of fifteen years, beginning in 1984, just after Ridley Scott’s monumental Orwellian commercial for the Macintosh personal computer debuted for the first (and last) time during the Superbowl. But rather than follow a progression of Jobs’ life with intimate, dramatized scenes encompassing significant events and relationships, Sorkin’s script breaks the action into three events: Jobs’ introduction of the Macintosh in Cupertino, California; his strategic unveiling of the NeXT Cube in 1988, five years after he was forced out of Apple; and then again in 1998, just after Jobs has regained control his former company to showcase the bestselling iMac—paving the way for iPods, iPhones, iPads, and countless other innovations.

It’s long overdue to mention his name in this review, but Michael Fassbender plays Jobs in a performance about as sublime as anything he’s done (see Hunger, Shame, or A Dangerous Method). With Jobs’ staff following him back and forth between dressing rooms and backstage, each of the three chapters in this triptych portraiture has him exacting his unruly, often unpopular demands on those close to him, the same few people at each location: His reliable marketing executive Joanna Hoffman (Kate Winslet, under a thin Polish accent); early techie partner Steve Wozniak (Seth Rogen); software designer Andy Herzfeld (Michael Stuhlbarg); Apple exec John Sculley (Jeff Daniels); irresponsible ex-girlfriend Chrisann Brennan (Katherine Waterston); and Jobs’ daughter with Chrisann, Lisa (played at various ages by Makenzie Moss, Ripley Sobo, and Perla Haney-Jardine). There are several overarching themes through these relationships, but the most affecting remains his attitude toward Lisa. At first, he can hardly be bothered to spare some of his $400 million, or even a minute of his time, to support Lisa and her mother; later, as time goes on, he has a softer approach, regret even.

Each relationship exists on multiple levels. We see shades of Jobs’ professional “reality distortion” with Hoffman, his unreasonable demands of Herzfeld, his stubbornness with Wozniak, his vindictiveness with Sculley, his cruelty with Chrisann, and his selfish heartlessness with Lisa. But in those same conversations inside dressing rooms and down hallways, we see Jobs demonstrate his affection for unwavering loyalty with Hoffman, his enduring competition with Wozniak, his capacity for self-reflection with Herzfeld, his talent for lying to himself with Sculley, and his eventually deep affection for his daughter. So much is required of Fassbender to achieve this role that, now, afterward, imagining anyone else try to accomplish what he does in the role is impossible. The film’s unsentimental view of the virtually unreachable man shows us how complicated he is, without using characters such as his actual wife and child (who are never mentioned) to make him into a sympathetic human being. He’s more complicated than a standard dramatic figure, and Fassbender’s performance proves just as multifaceted as Sorkin’s writing or Boyle’s direction.

Though some might argue the opposite, Boyle approaches the film with restraint. “Restraint” is meant with some exception, as Boyle demonstrating restraint represents another filmmaker’s highest degree of audacity. But his camera movements don’t surge with the wild ferocity of his work in Trainspotting (1996), 28 Days Later (2002), or the confined, but ostentatious 127 Hours (2010). Cinematographer Alwin Kuchler achieves off-kilter angles and an occasional swoosh, but it’s editor Elliot Graham who pieces Steve Jobs together in a sparkling tempo set to the beat of Sorkin’s dialogue. Boyle orchestrates superb performances from the entire ensemble, especially Fassbender and Winslet (though the whole cast is excellent). Covering the keyed up discourse with incredible fluidity, Boyle and Sorkin have achieved a film that shows us Jobs’ ability to inspire, his uncanny eye for design, his fastidious attention to detail, and his unwavering self-assurance. Although highly theatrical in Sorkin’s application of his dramaturgy, Steve Jobs also happens to be some of the best cinema offered in 2015.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review