Starship Troopers

By Brian Eggert |

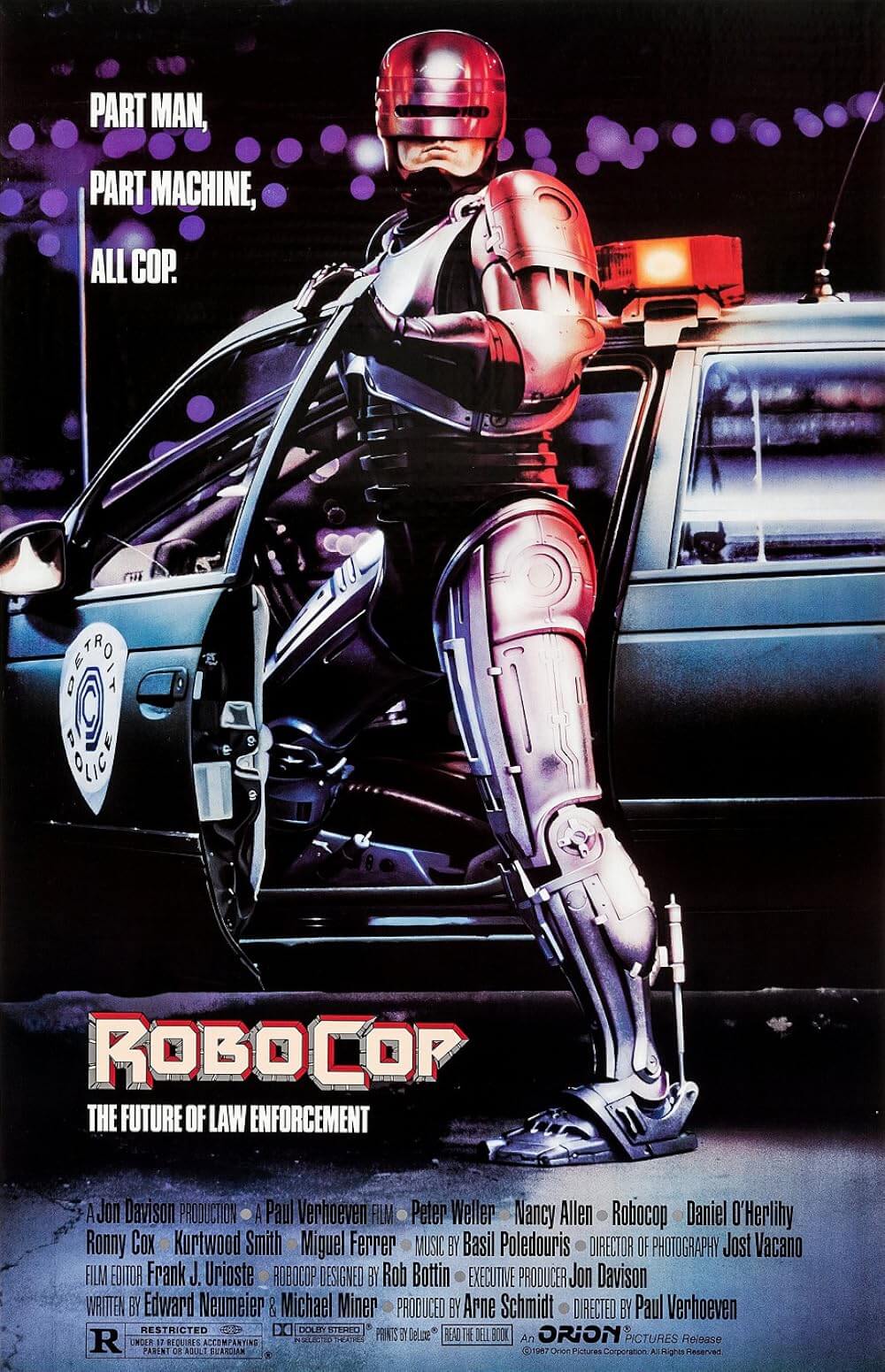

A polarizing work of epic science-fiction, right-wing politics, and savage violence, Starship Troopers is a popcorn movie that often incites either rambling celebration or absolute derision from its viewers. Based on Robert A. Heinlein’s book from 1959, the 1997 film adaptation represents another big-budget special FX extravaganza by Paul Verhoeven, whose experience with graphic bloodshed in sci-fi scenarios has been pushed to exceptional limits with RoboCop (1987) and Total Recall (1990). And like those films, Starship Troopers is funny, exciting, and a film with more to offer than just surface value. On the outside, we endure painful soap opera dramatics performed by talentless young actors; but underneath the corniness resides a rationale, a political satire that informs the entire picture and offers shrewd observations about a militarized society. If not for the film straining our patience with its attempts to create sympathy for its simple-minded characters, Starship Troopers might be a guiltless parody of totalitarian and wartime propaganda. Instead, discerning viewers must pardon a large portion of the film to uncover the intelligent and ironic commentary that subsists below the outward stupidity.

The story takes place in the distant future when the politics of Earth have reformatted into a fascistic meritocracy, and humans are engaged in a space war with the giant arthropod race of aliens called Arachnids, more commonly known as “Bugs”. Seemingly unintelligent creatures whose only mission is to propagate and spread, Arachnids hurl their Bug-infested asteroids into space to colonize other planets, and the militarized “Terran Federation” has been established to stop them. In largely ineffectual battles, countless grunts with machine guns unload hundreds of inadequate rounds into the never-ending onslaught of these 10-foot-high crab-like monsters—creatures that tear their victims to shreds without a moment’s hesitation. (I’m reminded of Jeff Goldblum’s metamorphosing character in The Fly, who comments, “Have you ever heard of insect politics? Neither have I. Insects don’t have politics. They’re very brutal. No compassion, no compromise.”) Who would ever subject themselves to such an absurdly bloody war, you ask? Well, joining the Federation is the only way to earn citizenship and vote in this world, and so youths who want to make a difference sign up, exposing themselves to gory warfare in which they’re helplessly dismembered, all in hopes of surviving and building a significant life for themselves. But that’s just the backdrop.

The film follows a group of high-schoolers from Buenos Aires, their various romances, and their prototypical “innocence lost” journey through basic training and into live combat. It’s an American world in Argentina, forcing us to wonder if the U.S. has since become a fascist state and achieved global domination. This very 90210-meets-Full Metal Jacket setup revolves around the dimwitted, Aryan-looking Johnny Rico (Casper Van Dien), a jock whose girlfriend Carmen (Denise Richards) has her eyes on another jock named Zander (Patrick Muldoon) from a competing school. Meanwhile, Dizzy (Dina Meyer) burns with a love unreciprocated by Johnny, and Carl (Neil Patrick Harris) has a torch for Dizzy. You guessed it, love stinks. They’re all thrust into the Bug war, Johnny and Dizzy relocated to infantry, Carmen and Zander to flight school, and Carl to military intelligence. The main storyline involves Johnny’s role in “Rasczak’s Roughnecks”, a gung-ho outfit led by Lt. Jean Rasczak (Michael Ironside), who barks rousing orders to his loyal troops. And when not involved in a grisly battle or schmaltzy romance, the film is relayed via an interactive pro-military propaganda machine, complete with brief news reports and informational pieces. At the end of each report, the viewer is asked, “Would you like to know more?”

The film follows a group of high-schoolers from Buenos Aires, their various romances, and their prototypical “innocence lost” journey through basic training and into live combat. It’s an American world in Argentina, forcing us to wonder if the U.S. has since become a fascist state and achieved global domination. This very 90210-meets-Full Metal Jacket setup revolves around the dimwitted, Aryan-looking Johnny Rico (Casper Van Dien), a jock whose girlfriend Carmen (Denise Richards) has her eyes on another jock named Zander (Patrick Muldoon) from a competing school. Meanwhile, Dizzy (Dina Meyer) burns with a love unreciprocated by Johnny, and Carl (Neil Patrick Harris) has a torch for Dizzy. You guessed it, love stinks. They’re all thrust into the Bug war, Johnny and Dizzy relocated to infantry, Carmen and Zander to flight school, and Carl to military intelligence. The main storyline involves Johnny’s role in “Rasczak’s Roughnecks”, a gung-ho outfit led by Lt. Jean Rasczak (Michael Ironside), who barks rousing orders to his loyal troops. And when not involved in a grisly battle or schmaltzy romance, the film is relayed via an interactive pro-military propaganda machine, complete with brief news reports and informational pieces. At the end of each report, the viewer is asked, “Would you like to know more?”

Many critics and viewers responded with a resounding “no” to that question in 1997, and since then, Starship Troopers has maintained the reputation of a brainless, one-dimensional hunk of blockbuster drivel. Starship Troopers is everything a 14-year-old could want out of a movie: Impressive CGI brings to life giant creepy-crawlies and elaborate spaceships, Verhoeven’s penchant for extreme violence realizes detailed battle scenes drenched in viscera, young hotties get naked, and an ironic sense of humor purveys throughout. Most appropriate was Richard Schickel’s observation in Time magazine: “The filmmakers are so lost in their slam-bang visual effects that they don’t give a hoot about the movie’s scariest implications.” Heinlein’s visionary Hugo Award-winning book was written as a story for juveniles, largely boys, and contains airs of classical 1950s sci-fi tales. Its influence reached far, from countless subsequent sci-fi authors to modern filmmakers (James Cameron’s grunts in Aliens were modeled after Heinlein’s troopers). The text provided its author with an entertaining way to communicate his outspoken right-wing political views, but the engaging philosophical and political discussions in the book have been stripped away in Verhoeven’s film in favor of celebrating the story’s more escapist elements.

This is not to suggest Starship Troopers is entirely devoid of political commentary; after all, the film’s heroes seem to get along well inside a fascist utopia. For the production, Verhoeven reteamed with his RoboCop screenwriter Ed Neumeier, who explores a similarly fascistic world to the one in their 1987 effort—both extreme worlds of big guns, heavy tech, coed locker rooms, and both presented to us through ironic, propagandistic newscasting. The aforementioned interactive broadcasts in Starship Troopers were modeled after Leni Riefenstahl’s Nazi propaganda piece Triumph of the Will (1935), but were likewise inspired by U.S. documentaries released during World War II (such as the seven-part feature Why We Fight, paid for by the U.S. government). And though the commentary of Starship Troopers is offset by buckets of blood, much like RoboCop, it contains elements of comic satire through a careful balance of irony and humor. Verhoeven and Neumeier invite us to laugh at the curious repression and brainwashing, to step back from the subjectivity of the characters and chew over the story’s alarming connotations. An early scene in Rasczak’s high-school political science course features the instructor discussing “the failure of Democracy” and announcing violence as “the supreme authority from which all other authority is derived” to a class of receptive minds eager to join the Federation, despite Rasczak’s lax warnings about the physical dangers of service.

This is not to suggest Starship Troopers is entirely devoid of political commentary; after all, the film’s heroes seem to get along well inside a fascist utopia. For the production, Verhoeven reteamed with his RoboCop screenwriter Ed Neumeier, who explores a similarly fascistic world to the one in their 1987 effort—both extreme worlds of big guns, heavy tech, coed locker rooms, and both presented to us through ironic, propagandistic newscasting. The aforementioned interactive broadcasts in Starship Troopers were modeled after Leni Riefenstahl’s Nazi propaganda piece Triumph of the Will (1935), but were likewise inspired by U.S. documentaries released during World War II (such as the seven-part feature Why We Fight, paid for by the U.S. government). And though the commentary of Starship Troopers is offset by buckets of blood, much like RoboCop, it contains elements of comic satire through a careful balance of irony and humor. Verhoeven and Neumeier invite us to laugh at the curious repression and brainwashing, to step back from the subjectivity of the characters and chew over the story’s alarming connotations. An early scene in Rasczak’s high-school political science course features the instructor discussing “the failure of Democracy” and announcing violence as “the supreme authority from which all other authority is derived” to a class of receptive minds eager to join the Federation, despite Rasczak’s lax warnings about the physical dangers of service.

Regardless of its political underpinnings, Starship Troopers suffers from what must be the worst-ever casting for a $100-plus million production, in specific reference to the central protagonist and his fellow Roughnecks. Van Dien, Richards, Muldoon, Meyer, and later costar Jake Busey are nothing short of dreadful, in some cases intolerable, and demonstrate a profound inability to read intentionally corny dialogue with any interpretive creativity. After Verhoeven’s flop Showgirls in 1995, they were all he could get. Much of the film’s satiric value is lost on the poor readings by the cast (the exceptions being Ironside, Clancy Brown, and Dean Norris). Until the CGI-driven Bug war scenes take over in the second half, the film is saddled with paper-thin characterizations established through cheesy dialogue. Then again, as one might expect, Verhoeven’s approach has more layers than the characters do. He wants the performances over-the-top; he wants them to seem fit for a soap opera, because only in such an unrealistic setting could such an equally over-the-top world become a reality. In this sense, some of Starship Troopers plays like a parody of itself—or at least Heinlein’s book—except the cast doesn’t appear to be in on Verhoeven’s joke. The director embraces the classical, rather old-fashioned setup of Heinlein’s novel, complete with 1950s notions of romance and duty, to incite his audience into a consideration of how the author’s extreme views are outdated. It’s a sly, commendable trick by the director; and yet, the experience remains punishing for the sizeable runtime spent on the characters’ dull personal lives and the actors portraying them.

Once the political commentaries have been canceled out by the performances, we’re left with the Federation war against the colonies of the Arachnid planet Klandathu in the second half. Verhoeven, whose family lived near The Hauge during WWII and witnessed a myriad of wartime atrocities, brings a remarkable power and authenticity to the violence and resulting corpses. Huge scenes filmed in the Badlands of Wyoming suggest an outgrowth from the interconnected hive of Bug holes, but soon the vacant landscape is filled with swarms of spidery things which leave only gobs of human flesh and armor in their wake. From under the ground’s surface emerge massive beetles that squirt bioluminescent projectiles into space in order to bring down orbiting Federation warships. Our uninteresting heroes engage in lethal battles, and the body count quickly rises, the pacing breakneck. By this time, we’re so swept up in the mindless entertainment value of the battle scenes—as they’re all realized with expensive, top-notch visuals—that any protests we might have about the actors or their characters have subsided until after the credits begin to roll. That the final half maintains momentum enough to allow us to forget the achingly shallow teen drama that came before is a testament to the film’s basic thrills.

Once the political commentaries have been canceled out by the performances, we’re left with the Federation war against the colonies of the Arachnid planet Klandathu in the second half. Verhoeven, whose family lived near The Hauge during WWII and witnessed a myriad of wartime atrocities, brings a remarkable power and authenticity to the violence and resulting corpses. Huge scenes filmed in the Badlands of Wyoming suggest an outgrowth from the interconnected hive of Bug holes, but soon the vacant landscape is filled with swarms of spidery things which leave only gobs of human flesh and armor in their wake. From under the ground’s surface emerge massive beetles that squirt bioluminescent projectiles into space in order to bring down orbiting Federation warships. Our uninteresting heroes engage in lethal battles, and the body count quickly rises, the pacing breakneck. By this time, we’re so swept up in the mindless entertainment value of the battle scenes—as they’re all realized with expensive, top-notch visuals—that any protests we might have about the actors or their characters have subsided until after the credits begin to roll. That the final half maintains momentum enough to allow us to forget the achingly shallow teen drama that came before is a testament to the film’s basic thrills.

Despite the notoriety of his early Hollywood résumé, Verhoeven’s disastrous Showgirls(1995) and the sour reputation of Starship Troopers (regardless of its mild box-office profits) solidified the edgy director’s decade-long decline, followed by another bomb in 2000 with Hollow Man. Not until 2006 did he return to his former glory with an exceptional Dutch-language WWII spy actioner, Black Book. Direct-to-video sequels and cult fandom of Starship Troopers have done little to improve the film’s widespread reputation over the years, perhaps because the first half remains so difficult to defend on any meaningful level, apart from its status as the guiltiest of movie pleasures. Even this critic’s arguments about its satiric, technical, and historical merits struggle to outweigh the significant failure of Verhoeven’s young cast and their melodramatic roles. No doubt, a more talented cast could have communicated the satiric spin Verhoeven was going for. But the film’s primeval thrust and testosterone-laden action, combined with the clever touches of irony injected by Verhoeven and Neumeier, result in an adventure so smart, and yet so inexplicably stupid, that the viewer cannot help but watch the film’s internal struggle with a glimmer of admiration.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review