Star Wars: Episode VI – Return of the Jedi

By Brian Eggert |

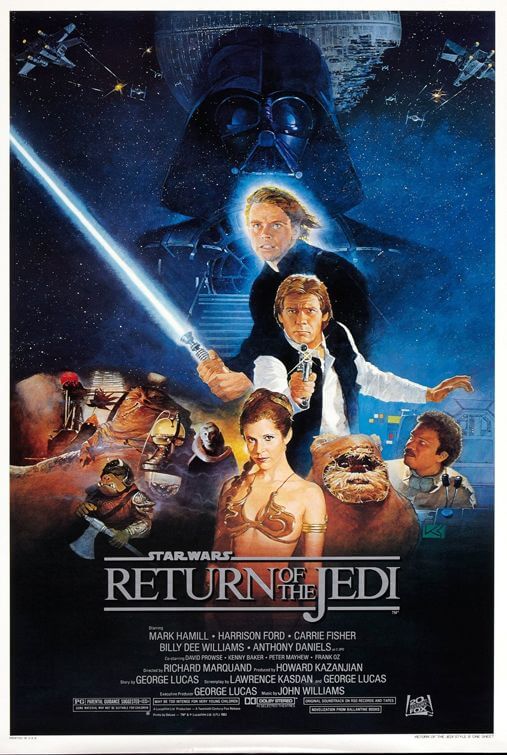

Entertaining and technically impressive though it may be, Star Wars – Episode VI: Return of the Jedi feels like an unnatural, forced conclusion to George Lucas’ original Star Wars trilogy. Several plot strains established in The Empire Strikes Back, and others contrived for the purpose of Return of the Jedi, were quickly wrapped up to offer audiences, and the creatively exhausted Lucas, a conclusion. Along with kernels of evidence in the previous film, Return of the Jedi demonstrates the extent to which Lucas was making up the mythology as he went, as opposed to having a grandiose master plan that he followed with each new episode—which is the impression he often gave in interviews. “This is what I always intended,” became Lucas’ blanket explanation. But Return of the Jedi doesn’t feel that way. As its development history demonstrates, the film was more about putting Star Wars to rest and giving audiences what they wanted. To be sure, many of the film’s plot elements feel compulsory, even if several sequences throughout the film remain memorable and transcend the rushed quality of the convenient storytelling.

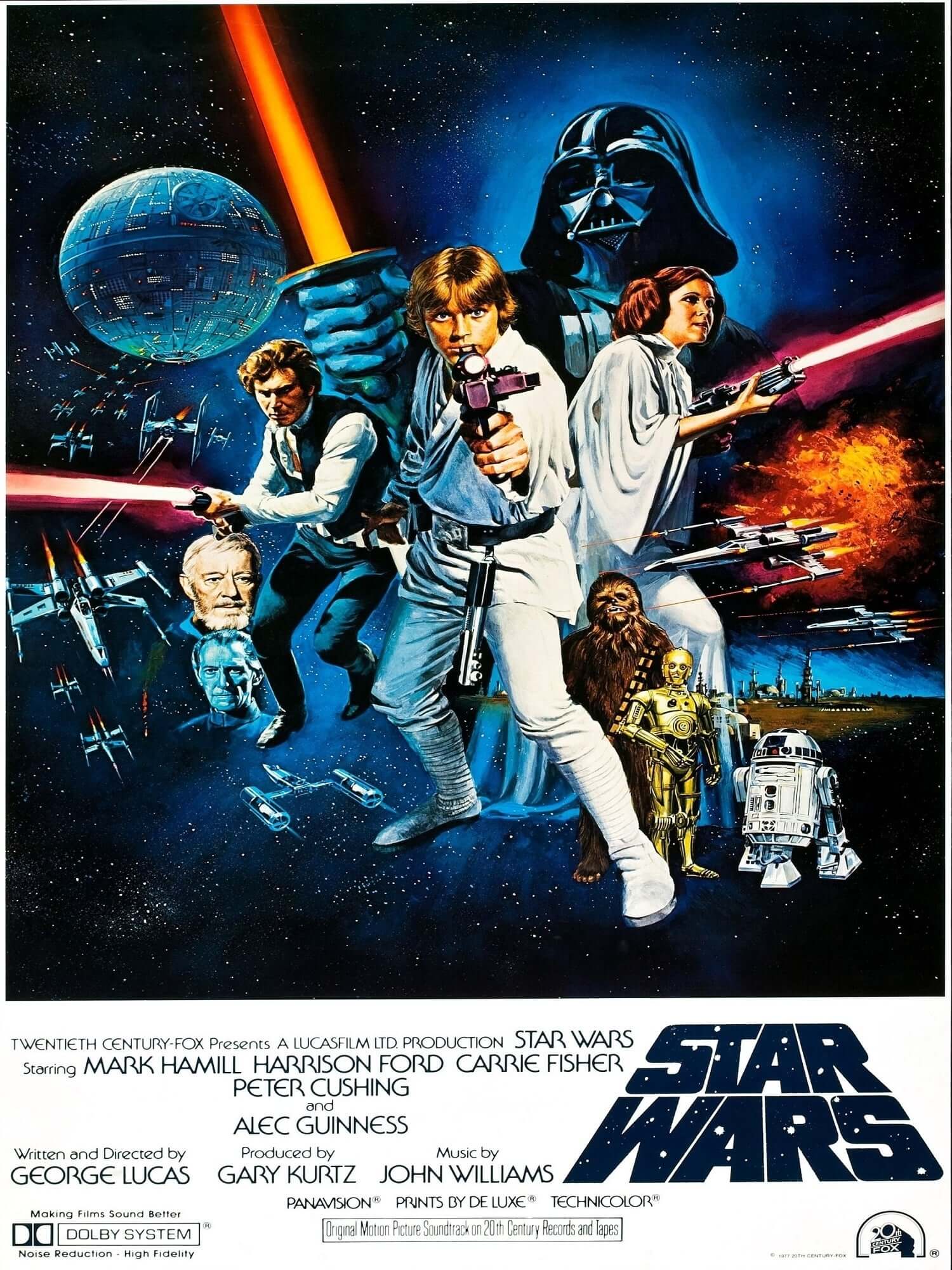

After the release of Star Wars in 1977, George Lucas had a grand vision for his space opera. Although tired of directing himself, he imagined each new sequel in his proposed saga would have a new director who could put their own personal touch on the material. Lucas planned on a total of nine films in all. These would include three prequels about the adventures of Obi-Wan Kenobi and young Anakin Skywalker, three films about Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader, and a third set of films about finally confronting the Emperor. In a 1980s issue of Starlog, Hamill suggested the development: “The Emperor should be the main bad guy—someone you try to get through nine movies, and in the ninth one you succeed.” But Lucas had an ulterior motive for hiring other directors. After writing, producing, and directing Star Wars, he was left physically and emotionally exhausted. And though he was only a producer on The Empire Strikes Back, a choice intended to lighten his workload and reduce stress, he remained an active participant. The strain began to affect his personal life, as he couldn’t just step away from overseeing the creative process behind his saga. “The sacrifice I’ve made for Star Wars may have been greater than I wanted,” he told Time in 1983. “I’m burned out. In fact, I was burned out a couple of years ago.”

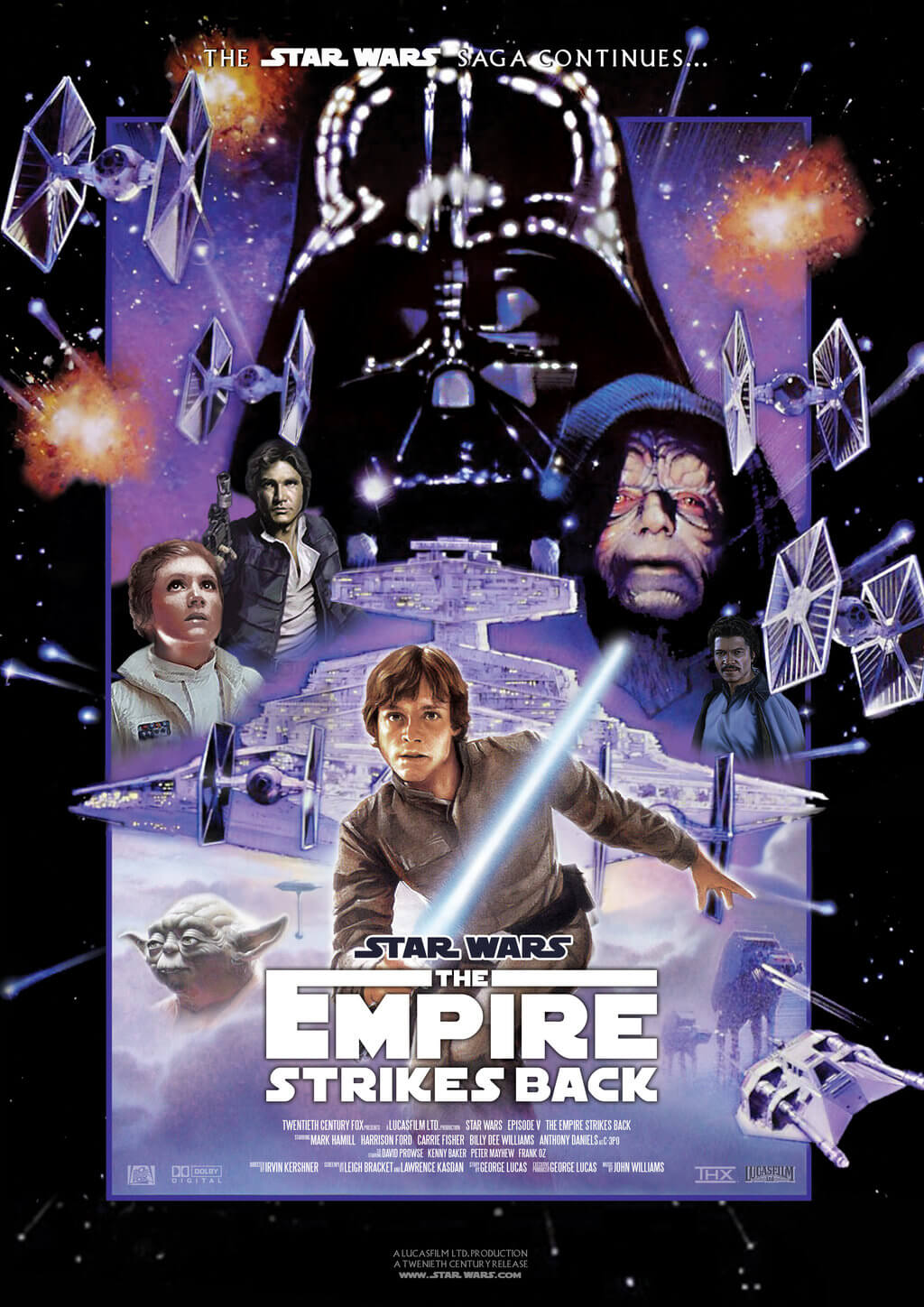

In many ways, Return of the Jedi was shaped by the creative disagreements and over-budget production of The Empire Strikes Back. Lucas jealously disagreed with many of the creative decisions made by director Irvin Kershner, despite his original plan to allow directors creative freedom. Even more stressful for Lucas was that his producer Gary Kurtz and screenwriter Lawrence Kasdan often took Kershner’s side. As a result, Lucas now felt that no director should be allowed to put their spin on his saga; instead, he would hire directors who would take his detailed instruction. Even still, he could not imagine carrying on this way, in what amounted to another twenty years of arduous filming. Before the release of The Empire Strikes Back, Lucas had reconsidered whether it was necessary to continue his Star Wars saga beyond a third entry and, in some respects, he regretted his initial ambitions for more than three episodes and re-labeling Star Wars as “Episode IV”. His solution was to whittle down four films’ worth of story into a single feature: Return of the Jedi, originally called “Revenge of the Jedi”. As film historian Michael Kaminski put it, “He wanted to wrap up the series as quickly, easily and cheaply as possible.”

In many ways, Return of the Jedi was shaped by the creative disagreements and over-budget production of The Empire Strikes Back. Lucas jealously disagreed with many of the creative decisions made by director Irvin Kershner, despite his original plan to allow directors creative freedom. Even more stressful for Lucas was that his producer Gary Kurtz and screenwriter Lawrence Kasdan often took Kershner’s side. As a result, Lucas now felt that no director should be allowed to put their spin on his saga; instead, he would hire directors who would take his detailed instruction. Even still, he could not imagine carrying on this way, in what amounted to another twenty years of arduous filming. Before the release of The Empire Strikes Back, Lucas had reconsidered whether it was necessary to continue his Star Wars saga beyond a third entry and, in some respects, he regretted his initial ambitions for more than three episodes and re-labeling Star Wars as “Episode IV”. His solution was to whittle down four films’ worth of story into a single feature: Return of the Jedi, originally called “Revenge of the Jedi”. As film historian Michael Kaminski put it, “He wanted to wrap up the series as quickly, easily and cheaply as possible.”

Lucas intended the Star Wars sequels to place emphasis on plot more than characters—to make them fast-moving and heavy on action, like an adventure serial. Kershner and Kasdan had the opposite approach for The Empire Strikes Back. Lucas didn’t care much for The Empire Strikes Back and wanted something simpler for Return of the Jedi. Yet, to some extent, the plot of the second film would not allow for a simpler approach, because Lucas originally believed he had Episodes V-IX to develop his ongoing saga. Instead, several subplots established in The Empire Strikes Back had to be quickly resolved in the third film. After all, audiences were left with countless questions: Was Darth Vader telling the truth about being Luke’s father, and if so, was Obi-Wan lying when he originally told Luke that Vader betrayed and killed Luke’s real father? Would Han Solo be saved from Jabba the Hutt? Harrison Ford initially had no interest in returning for a third film, and unlike his castmates Mark Hamill and Carrie Fisher, he wasn’t contractually obligated to reprise the role. Who would end up with Leia, Luke or Han? And then there’s the “Other” mentioned on Dagobah (Yoda and Obi Wan’s spirit talk about Luke. Obi-Wan says, “He is our only hope.” Yoda replies, “No… there is another.”) Who exactly was Yoda talking about? If there’s another Jedi out there, why have we been following Luke for two films?

All of these questions needed answering and very few of them were addressed in Lucas’ first treatment for “Revenge of the Jedi”—which dwelled more on Vader’s internal struggles and his bond to Luke. Once Lucas decided to end the entire series in a trilogy, he realized he had written himself into a corner and his original treatment had to be scrapped. Though many components of that draft remain in the final film, the finished script spends more time addressing the aforementioned questions. During story conferences, it was decided that Leia would be revealed as both Luke’s sister and the “Other” (though she displays no real Jedi powers). Although Leia was the most logical choice to fill these roles, it also created several plot holes left to be gracelessly filled in throughout the prequel trilogy. For example, Leia says she remembers her mother, yet her mother dies giving birth in Revenge of the Sith (2005). And there were also fans to consider. Han Solo was a beloved character, and Harrison Ford’s newly minted celebrity after Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) made Han more popular than ever. They couldn’t just leave him in the clutches of Jabba the Hutt. “This whole sequence with Jabba the Hutt,” Lucas remarked in a DVD commentary from 2004, “was more an afterthought than anything else, because Han Solo had become such a popular character.” With all of this in mind, Lucas wrote a rough draft of Return of the Jedi and gave it to Kasdan to finish.

All of these questions needed answering and very few of them were addressed in Lucas’ first treatment for “Revenge of the Jedi”—which dwelled more on Vader’s internal struggles and his bond to Luke. Once Lucas decided to end the entire series in a trilogy, he realized he had written himself into a corner and his original treatment had to be scrapped. Though many components of that draft remain in the final film, the finished script spends more time addressing the aforementioned questions. During story conferences, it was decided that Leia would be revealed as both Luke’s sister and the “Other” (though she displays no real Jedi powers). Although Leia was the most logical choice to fill these roles, it also created several plot holes left to be gracelessly filled in throughout the prequel trilogy. For example, Leia says she remembers her mother, yet her mother dies giving birth in Revenge of the Sith (2005). And there were also fans to consider. Han Solo was a beloved character, and Harrison Ford’s newly minted celebrity after Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) made Han more popular than ever. They couldn’t just leave him in the clutches of Jabba the Hutt. “This whole sequence with Jabba the Hutt,” Lucas remarked in a DVD commentary from 2004, “was more an afterthought than anything else, because Han Solo had become such a popular character.” With all of this in mind, Lucas wrote a rough draft of Return of the Jedi and gave it to Kasdan to finish.

Kershner was not asked to return as the director given his creative differences with Lucas. David Lynch (Blue Velvet) was approached but turned down the opportunity, as Lucas would not hand over complete creative authority. Because he was shooting outside of Hollywood, Lucas’ options were limited to directors who were not a part of the union. He eventually found Richard Marquand (Eye of the Needle, 1981) and producer Howard Kazanjian told Marquand that, as director, “You’re representing his wishes”—referring, of course, to Lucas, who planned to be on set and personally supervise the shoot. Marquand later remarked, “It is rather like trying to direct King Lear with Shakespeare in the next room.” Nevertheless, Marquand agreed with Lucas that they should employ a style that made Return of the Jedi “available to children”. It’s a style that, in 1983, Hamill described as a “smash-and-grab” technique. The evolution from A New Hope to The Empire Strikes Back represents a progression from a comic-book movie to sophisticated, operatic storytelling and filmmaking. Return of the Jedi took a step back, far back, and revisited the comic-book style of the original. When A New Hope debuted that style, Lucas’ innovative treatment of classical archetypes was fresh and exciting. By 1983, the Star Wars phenomenon had saturated the filmic marketplace with Star Wars-like films. Embracing that style again, in a scenario that bears close similarities to A New Hope no less, feels obligatory, overtly commercial, and less innovative.

The film opens with a long sequence in which Han Solo is rescued and Jabba the Hutt destroyed. Han and Leia rejoin the Rebels, while Luke heads to Dagobah to finally become a Jedi. On his deathbed, Yoda reveals “there is another Skywalker,” and tells Luke that he must confront Vader to complete his Jedi training. The ghost of Obi-Wan then appears and confirms Leia is actually Luke’s sister, and the Force is strong with her. Later, Luke meets up with the Rebels and learns the Empire has somehow built a second Death Star, for which the Rebels have discovered yet another singular vulnerability reached only by flying down yet another long trench (they know all of this because yet another group of rebels secretly obtained the schematics). The new Death Star now houses the evil Emperor (Ian McDiarmid) and orbits the forest moon Endor, where a shield array protects the station. With the help of Endor’s furry bear-people called Ewoks, Han and Leia bring down the shield. Lando Calrissian (Billy Dee Williams) and the rest of the Rebel forces attack the Death Star in space. Meanwhile, Luke confronts Vader on the Death Star, finds the good in him, and turns him against the Emperor, but not before the Emperor deals a mortal blow to Vader. Once the Emperor is dead and the Death Star destroyed, everyone in the galaxy celebrates.

The film opens with a long sequence in which Han Solo is rescued and Jabba the Hutt destroyed. Han and Leia rejoin the Rebels, while Luke heads to Dagobah to finally become a Jedi. On his deathbed, Yoda reveals “there is another Skywalker,” and tells Luke that he must confront Vader to complete his Jedi training. The ghost of Obi-Wan then appears and confirms Leia is actually Luke’s sister, and the Force is strong with her. Later, Luke meets up with the Rebels and learns the Empire has somehow built a second Death Star, for which the Rebels have discovered yet another singular vulnerability reached only by flying down yet another long trench (they know all of this because yet another group of rebels secretly obtained the schematics). The new Death Star now houses the evil Emperor (Ian McDiarmid) and orbits the forest moon Endor, where a shield array protects the station. With the help of Endor’s furry bear-people called Ewoks, Han and Leia bring down the shield. Lando Calrissian (Billy Dee Williams) and the rest of the Rebel forces attack the Death Star in space. Meanwhile, Luke confronts Vader on the Death Star, finds the good in him, and turns him against the Emperor, but not before the Emperor deals a mortal blow to Vader. Once the Emperor is dead and the Death Star destroyed, everyone in the galaxy celebrates.

In some ways, the laziness of Return of the Jedi‘s story resulted from the Star Wars phenomenon. Consider Darth Vader, the relentless and vindictive bad guy from Star Wars. In Return of the Jedi, he would be humanized to maintain his status as an enduring cult icon. When Hamill talked to Starlog in his 1980 interview, before knowing plot details about Return of the Jedi, he said, “I think, originally, if you follow classic drama, I would have to kill [Darth Vader] in the third episode. But now he’s a cult figure and, in a way, George may not want to do away with him.” This choice of humanizing Vader ultimately led to the formation of the prequel trilogy’s narrative arc, being about the corruption of Anakin to the Dark Side. In another way, because Lucas was simply tired of Star Wars and resolved to end the franchise after three films, plot elements are grossly underdeveloped. When Leia is revealed to be Luke’s twin sister, not only does the development border on ludicrousness, but the fulfillment of that hope never lives up to its promise. After all, Leia never develops her ability to use the Force; it is Luke’s confrontation of Vader and the Emperor that leads to the downfall of the Empire. The promise of the “Other” was derived from Lucas’ plans for a nine-film saga, and the final trilogy after Return of the Jedi would highlight the Emperor’s demise and, presumably, Leia’s rise as a Jedi. However, Lucas abridged his grand design out of sheer Star Wars fatigue, and so the plot element plays almost no role in the original trilogy.

Michael Kaminski’s book The Secret History of Star Wars notes, “Lucasfilm press material would later state… he had all nine episodes written out and that he merely picked the fourth entry… But the only script Lucas had was Star Wars, a single, stand-alone film, with various early drafts that did not contain the plots for the additional episodes.” How else can one explain the incongruities between A New Hope and Return of the Jedi, or the awkward resolution of Luke learning that Vader is his father, and then confronting Obi-Wan about what he was originally told? Obi-Wan explains, “What I told you is true… from a certain point of view.” And in response, Hamill takes a tone that seems to exemplify the feelings of the audience, echoing with disbelief, “‘From a certain point of view’?” Elsewhere, Return of the Jedi makes quick work of interesting characters. Fans of Boba Fett find no solace in his slapdash demise: he’s accidentally struck by Han and sent falling into the mouth of a desert beast with a pathetic cry. But these observations are not to suggest the film is irredeemable; they simply take what could have been a fascinating saga and truncate it. The result entertains, particularly the Jabba’s palace sequence and the scenes on Endor (however cutesy they may be). The Rebel raid on the Death Star showcases impressive visuals; and the mood of the scene between Luke, Vader, and the Emperor remains tense.

Michael Kaminski’s book The Secret History of Star Wars notes, “Lucasfilm press material would later state… he had all nine episodes written out and that he merely picked the fourth entry… But the only script Lucas had was Star Wars, a single, stand-alone film, with various early drafts that did not contain the plots for the additional episodes.” How else can one explain the incongruities between A New Hope and Return of the Jedi, or the awkward resolution of Luke learning that Vader is his father, and then confronting Obi-Wan about what he was originally told? Obi-Wan explains, “What I told you is true… from a certain point of view.” And in response, Hamill takes a tone that seems to exemplify the feelings of the audience, echoing with disbelief, “‘From a certain point of view’?” Elsewhere, Return of the Jedi makes quick work of interesting characters. Fans of Boba Fett find no solace in his slapdash demise: he’s accidentally struck by Han and sent falling into the mouth of a desert beast with a pathetic cry. But these observations are not to suggest the film is irredeemable; they simply take what could have been a fascinating saga and truncate it. The result entertains, particularly the Jabba’s palace sequence and the scenes on Endor (however cutesy they may be). The Rebel raid on the Death Star showcases impressive visuals; and the mood of the scene between Luke, Vader, and the Emperor remains tense.

Today, Return of the Jedi proves to be the most difficult film to revisit in the original trilogy; in subsequent years, Lucas tampered with it more than others—or at least it seems that way. When he released altered editions of Return of the Jedi in 1997 and 2004, new footage and CGI additions were incorporated into the film. These include a nauseating sequence in Jabba’s palace where computer-generated characters sing, their mouths popping out at the viewer seemingly in anticipation of a 3-D post-conversion. Of all the changes made to the original trilogy over the years, this single scene proves the most gratuitous and downright insulting to any viewer. The newer editions made other changes, such as Vader shouting “Nooo!” as the Emperor zaps Luke or incorporating Hayden Christensen (Anakin in Attack of the Clones and Revenge of the Sith) as Anakin’s ghost in the final scenes (Sebastian Shaw, the actor who played the unmasked Vader, was deleted). The last moments leave us with a sour taste about the entire experience, as Lucas replaces the beloved Ewok song “Yub Nub” with an orchestral finish and shots of various CGI cities from the prequels celebrating the rebel victory. The computerized images create a distracting contrast of style, from the practical FX of the original to the digital painting of Lucas’ prequels.

Very little stylistic or thematic consistency exists between the original trilogy’s films, more now than ever thanks to Lucas’ subsequent tampering. In that sense, Lucas’ otherwise deplorable prequel trilogy seems more cohesive. Nevertheless, Return of the Jedi displays greater visual craftsmanship and effects than anything before or after it in Lucas’ saga, having been made at the height of practical movie magic and before digitization took over Hollywood. But Return of the Jedi remains the film where questions are either left unanswered or are addressed in unsatisfying ways. To Lucas, how the story worked out was less important than rehashing A New Hope and ending the series with a bang. Perhaps because he could make his prequel trilogy faster, with computers doing most of the work, he employed the same “smash-and-grab” technique years later. Given how well Return of the Jedi was put together from a technical perspective, and how entertaining the whole thing ends up being, it’s difficult not to enjoy the film on very basic levels, but it stands as the original trilogy’s odd man out.

Very little stylistic or thematic consistency exists between the original trilogy’s films, more now than ever thanks to Lucas’ subsequent tampering. In that sense, Lucas’ otherwise deplorable prequel trilogy seems more cohesive. Nevertheless, Return of the Jedi displays greater visual craftsmanship and effects than anything before or after it in Lucas’ saga, having been made at the height of practical movie magic and before digitization took over Hollywood. But Return of the Jedi remains the film where questions are either left unanswered or are addressed in unsatisfying ways. To Lucas, how the story worked out was less important than rehashing A New Hope and ending the series with a bang. Perhaps because he could make his prequel trilogy faster, with computers doing most of the work, he employed the same “smash-and-grab” technique years later. Given how well Return of the Jedi was put together from a technical perspective, and how entertaining the whole thing ends up being, it’s difficult not to enjoy the film on very basic levels, but it stands as the original trilogy’s odd man out.

Sources:

Bailey, T. J. Devising a Dream: A Book of Star Wars Facts and Production Timeline. Louisville, KY: Wasteland Press, 2005.

Baxter, John. Mythmaker: The Life and Work of George Lucas (1st ed.). New York: William Morrow, 1999.

Bouzereau, Laurent. Star Wars: The Annotated Screenplays. New York: Del Rey, 1997.

Hearn, Marcus. The Cinema of George Lucas. New York: ABRAMS Books, 2005.

Kaminski, Michael. The Secret History of Star Wars: The Art of Storytelling and the Making of a Modern Epic. Kingston, Ont.: Legacy Books Press, 2008.

Rinzler, J.W. The Making of Star Wars. LucasBooks, 2007.

Sansweet, Stephen (1992). Star Wars: From Concept to Screen to Collectible. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review