Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back

By Brian Eggert |

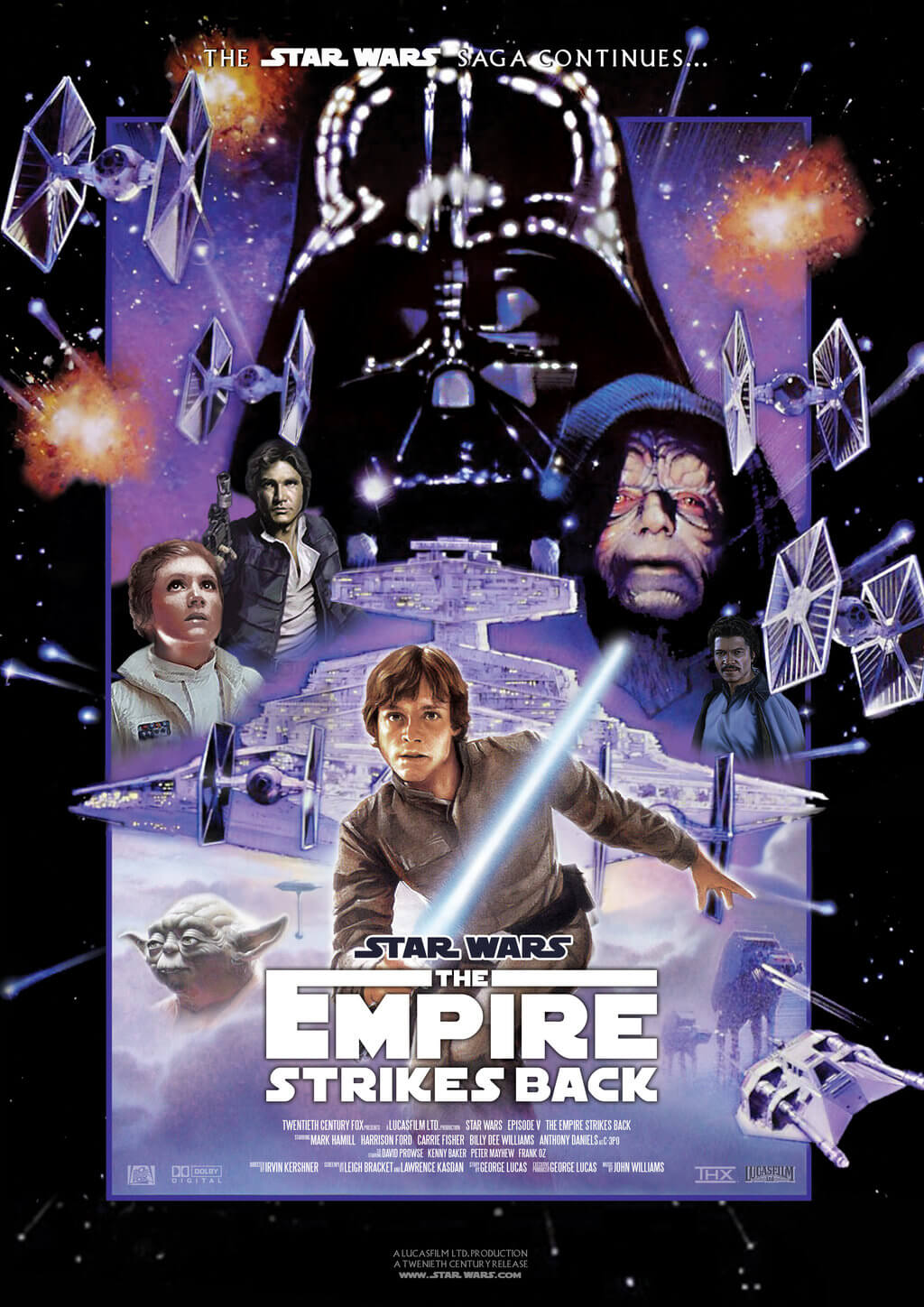

Forgive the generalization, but Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back is one of the most beloved films of all time and certainly the most well-crafted of the Star Wars films. Any Star Wars aficionado, as well as most critics and film historians, will no doubt proclaim it to be the best in the series, often with wildly enthusiastic aplomb. It belongs on a list next to The Godfather, Part II and Aliens for being a sequel which fans commonly argue betters its original. Often noted for its thematic darkness and the touch of gray it brings to the otherwise black-and-white comic-book world of the original, The Empire Strikes Back also happens to be the finest Star Wars film in its formal accomplishments, dramatic expansion, and deepening of the galaxy created by George Lucas in 1977. And yet, the film marks the beginning of a series of incongruities that continue through the remaining Star Wars sequels and prequels, each diminishing the singularity of the original film. Examining the creative process of this first sequel demonstrates how Lucas’ regular story revisions diverge from the established mythology—that his Star Wars saga was an ever-evolving and occasionally clumsy evolutionary process, as opposed to later claims that he sketched out or even wrote entire stories for each Star Wars film long before production began. Regardless of how it was created, The Empire Strikes Back rises above its inconsistencies to enhance the overall legacy and provide fans with the most dramatically involving entry in the series.

After the release (and several re-releases) of Star Wars, the film incited a popular phenomenon. Perhaps craze is a better word. What else but a “craze” could result in Kellog’s C-3PO’s cereal, complete with a mail-in offer for a C-3PO mask? Kenner’s ground-breaking toy line offered an action figure of every character, no matter how obscure. Along with comic books, novelizations, a notorious Christmas special, and countless other promotional tie-ins, Star Wars would not soon be forgotten by audiences. It also rejuvenated the otherwise dead fantasy and adventure genres, justifying titles like Superman (1978), Conan the Barbarian (1982), and television shows such as Buck Rogers in the 25th Century (1979-1981). Though Lucas intended little more than an escapist B-movie adventure made in a high-quality style, audiences received Star Wars as a type of religion, going far beyond its pop-culture implications. Even critics returned to the film and found all manner of hidden meanings, largely scholarly projections not intended by the filmmaker. Lucas’ use of familiar, heroic archetypes could not help but feel familiar and important to audiences, yet actually empty enough to allow viewers to project onto it any meaning of their choosing. And so, when Lucas resolved to develop a Star Wars sequel, he, too, had built Star Wars up into something far more grandiose than he intended. Lucas designed his franchise to resemble Flash Gordon matinee serials, each of which ended with a cliffhanger to ensure the audience returned for next week’s episode. That structure, along with the desire to embrace the aggrandized Star Wars phenomenon, resulted in an incomplete, episodic nature for his sequel.

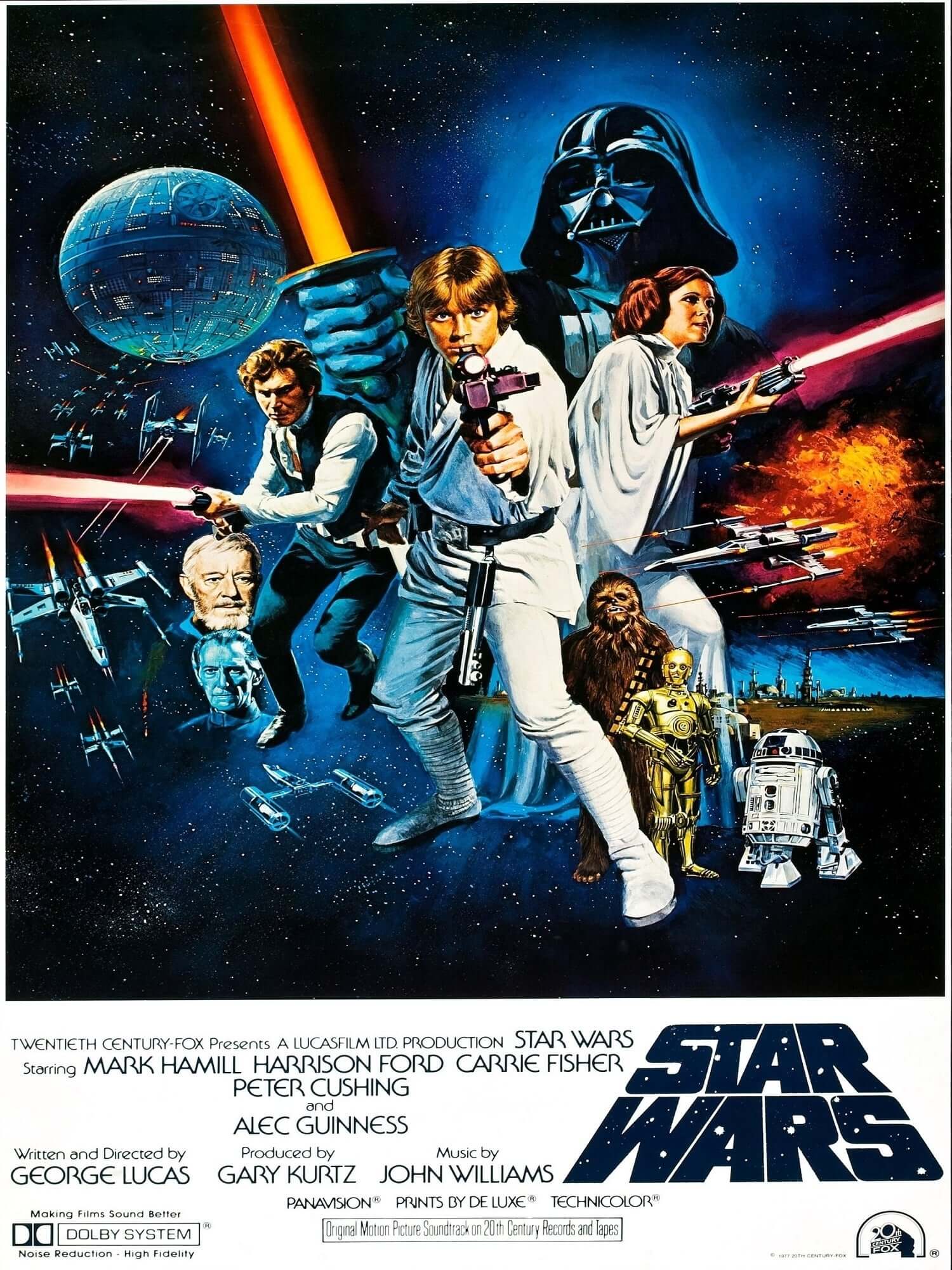

Lucas embraced the hype and used it. Whether by design or misconception, after the release of Star Wars, Lucas perpetuated the notion in the media that he had already conceived all entries of his franchise, creating unbridled anticipation for his Biblical-sized, multi-film epic. And why not? It certainly secured the future commercial success of the series, and it veiled the usual writing process under a blanket of intention. When The Empire Strikes Back debuted in theaters in 1980, it featured a strange addition to the opening’s scrolling titles—the full title read Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back. This appeared long before Lucas’ prequel trilogy and without an onscreen explanation as to why the first film was now apparently the fourth. And when the original Star Wars was re-released into theaters in 1981, the film now featured subtitles: Episode IV – A New Hope. Today we can only imagine the audience’s reaction and confusion. Nevertheless, it established the episodic nature of Star Wars and Lucas’ initial design for the franchise. Moviegoers savored the promise of more, even if it meant years between films. Rather than admit that he, like any writer-director, was making things up as he went along and had to sift through countless transformations and terrible ideas before he achieved the final story, he could say, “This is what I always intended.” This approach also shielded Lucas from any criticisms, despite the defense being transparent.

Lucas embraced the hype and used it. Whether by design or misconception, after the release of Star Wars, Lucas perpetuated the notion in the media that he had already conceived all entries of his franchise, creating unbridled anticipation for his Biblical-sized, multi-film epic. And why not? It certainly secured the future commercial success of the series, and it veiled the usual writing process under a blanket of intention. When The Empire Strikes Back debuted in theaters in 1980, it featured a strange addition to the opening’s scrolling titles—the full title read Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back. This appeared long before Lucas’ prequel trilogy and without an onscreen explanation as to why the first film was now apparently the fourth. And when the original Star Wars was re-released into theaters in 1981, the film now featured subtitles: Episode IV – A New Hope. Today we can only imagine the audience’s reaction and confusion. Nevertheless, it established the episodic nature of Star Wars and Lucas’ initial design for the franchise. Moviegoers savored the promise of more, even if it meant years between films. Rather than admit that he, like any writer-director, was making things up as he went along and had to sift through countless transformations and terrible ideas before he achieved the final story, he could say, “This is what I always intended.” This approach also shielded Lucas from any criticisms, despite the defense being transparent.

Such a defense would allow him to make changes to the original films, to create no end of future episodes, secure him limitless commercial prospects, and in the meantime make him look like a genius for continuing the process of bringing his preordained vision to the screen. Indeed, The Empire Strikes Back became the first film to signal Lucas’ wealth of ideas concerning his saga of characters and stories only hinted at in Star Wars, which in turn allowed his franchise expansive growth opportunities. He could make films about the civil war, Darth Vader’s origin story, the Clone Wars, or the adventures of young Obi Wan Kenobi and young Anakin Skywalker. All of these ideas required new casting and reimagined special FX, but they were stories Lucas wanted to tell. In keeping with the momentum of the now-retitled A New Hope, Lucas resolved the easiest solution would be to deliver a direct sequel Star Wars, while also allowing for those other stories to be told at some later time. “That’s where the [eventual idea of] starting in episode four came,” said Lucas in a 1997 interview. “Because I said, ‘Well, maybe I could make three out of this back story.’ That evolved right around the time [Star Wars] was released, after I knew it was a success.” With so much story, it meant Lucas had endless episodes, and thus endless commercial potential. In fact, Lucas had initially planned on eleven additional films after Star Wars, as reported in Time magazine in 1978, with constant filming and 2001 as the expected debut of the final episode—not unlike a twelve-part serial series. Eventually, he shortened that ambitious plan down to nine films in all.

The reality of his creative process was far more conventional than he revealed. But then, Lucas had a lot of contradictory remarks after the debut of Star Wars, no doubt because it was the most successful film ever made and the potential for more was limitless. With that potential and its certain unlimited income for Lucas, the filmmaker envisioned building a “research center” eventually known as Skywalker Ranch. Because Lucas had always been more interested in experimenting with film, Skywalker Ranch could provide him with an isolated workspace to test new technologies and methods. In that sense, the Star Wars sequel was very much a cash-cow for Lucas to fund his personal projects (Skywalker Ranch would cost almost $20 million). With his mind elsewhere and his experience directing Star Wars a painful memory, Lucas wanted other talent working on the sequel. During the filming of Star Wars, Lucas suffered bouts of hypertension and exhaustion over the stressful production. “I hate directing,” he told Rolling Stone in a 1980 interview. “It’s like fighting a fifteen-round heavyweight bout with a new opponent every day. You go to work knowing just how you want a scene to be, but by the end of the day, you’re usually depressed because you didn’t do a good enough job.” Lucas soon resolved to be executive producer and perhaps contribute to the sequel’s script, allowing another director to take over in his stead. He equated this approach to a film school project where several students would approach the same theme but each interprets that theme in a unique way.

The reality of his creative process was far more conventional than he revealed. But then, Lucas had a lot of contradictory remarks after the debut of Star Wars, no doubt because it was the most successful film ever made and the potential for more was limitless. With that potential and its certain unlimited income for Lucas, the filmmaker envisioned building a “research center” eventually known as Skywalker Ranch. Because Lucas had always been more interested in experimenting with film, Skywalker Ranch could provide him with an isolated workspace to test new technologies and methods. In that sense, the Star Wars sequel was very much a cash-cow for Lucas to fund his personal projects (Skywalker Ranch would cost almost $20 million). With his mind elsewhere and his experience directing Star Wars a painful memory, Lucas wanted other talent working on the sequel. During the filming of Star Wars, Lucas suffered bouts of hypertension and exhaustion over the stressful production. “I hate directing,” he told Rolling Stone in a 1980 interview. “It’s like fighting a fifteen-round heavyweight bout with a new opponent every day. You go to work knowing just how you want a scene to be, but by the end of the day, you’re usually depressed because you didn’t do a good enough job.” Lucas soon resolved to be executive producer and perhaps contribute to the sequel’s script, allowing another director to take over in his stead. He equated this approach to a film school project where several students would approach the same theme but each interprets that theme in a unique way.

Star Wars was still a relatively recent phenomenon, but its mythology was already cemented into pop-culture. Notions of Darth Vader, the Force, and Luke Skywalker’s eventual emergence as a Jedi Knight could be explored by other talent in the sequel. Lucas thought about who could write the script and remembered reading pulp science-fiction from writer Leigh Brackett years earlier. He decided to contact her and called, asking if she had written any scripts before. Brackett replied with her credits, including The Big Sleep (1946) and more recently The Long Goodbye (1973). Lucas was shocked to discover the Leigh Brackett who wrote far-out sci-fi yarns for Amazing Stories and Planet Stories magazines was the very same writer who collaborated with Howard Hawks on Rio Bravo (1958) and other pictures. Lucas and Brackett fleshed-out the first outline in 1977, while Brackett and Lawrence Kasdan would complete the script. Once again, Lucas drew inspiration for the story structure from Japanese master Akira Kurosawa, referencing Dersu Uzala (1975), particularly for the ice planet Hoth and bog planet Dagobah sequences. The titular character of Kurosawa’s film, an Asiatic recluse who serves as a guide for Russian explorers, even has the same naive charm as Yoda; but like Yoda, the character proves to be very wise.

The film begins on Hoth, where the Rebels’ base is invaded. The Rebels fight back and after escaping, Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) goes off to train with Jedi master Yoda (voice of Frank Oz), while Han Solo (Harrison Ford) and Leia (Carrie Fisher) are pursued by the Empire. They escape to the cloud city of Bespin, where Han’s friend Lando Calrissian (Billy Dee Williams) offers assistance. But Darth Vader and the Empire have already arrived and set a trap; they capture Han, leading to a confrontation between Luke and Vader, where the villain reveals, “Luke… I am your father.” More than any other single Star Wars film, The Empire Strikes Back allows the villains their due. By the last scenes, Vader has the upper hand in the struggle between the Empire and Rebellion, bounty hunter Boba Fett makes his way to Tatooine with his prisoner Han Solo, and the heroes can do nothing else except regroup and lick their wounds. And yet, between the first film and second, characters change in ways not congruous with what was established in Star Wars. Darth Vader goes from being a third- or fourth-string villain to dominating the galaxy under the Emperor. The shift occurred largely because of audience reactions to Star Wars. After all, audiences loved to hate Darth Vader—with his Nazi helmet and black costume that so efficiently personify evil—to such an extent that Lucas had no choice but to shape the sequel around him. “Darth Vader became such an icon in the first film,” he told an interviewer. “That icon of evil sort of took over everything, much more than I intended.”

The film begins on Hoth, where the Rebels’ base is invaded. The Rebels fight back and after escaping, Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) goes off to train with Jedi master Yoda (voice of Frank Oz), while Han Solo (Harrison Ford) and Leia (Carrie Fisher) are pursued by the Empire. They escape to the cloud city of Bespin, where Han’s friend Lando Calrissian (Billy Dee Williams) offers assistance. But Darth Vader and the Empire have already arrived and set a trap; they capture Han, leading to a confrontation between Luke and Vader, where the villain reveals, “Luke… I am your father.” More than any other single Star Wars film, The Empire Strikes Back allows the villains their due. By the last scenes, Vader has the upper hand in the struggle between the Empire and Rebellion, bounty hunter Boba Fett makes his way to Tatooine with his prisoner Han Solo, and the heroes can do nothing else except regroup and lick their wounds. And yet, between the first film and second, characters change in ways not congruous with what was established in Star Wars. Darth Vader goes from being a third- or fourth-string villain to dominating the galaxy under the Emperor. The shift occurred largely because of audience reactions to Star Wars. After all, audiences loved to hate Darth Vader—with his Nazi helmet and black costume that so efficiently personify evil—to such an extent that Lucas had no choice but to shape the sequel around him. “Darth Vader became such an icon in the first film,” he told an interviewer. “That icon of evil sort of took over everything, much more than I intended.”

To be sure, the first draft of The Empire Strikes Back contained no reference to the pivotal moment when Darth Vader reveals he’s Luke’s father, but it contained other ideas that were dropped and used later in Lucas’ prequels. Boba Fett’s connection to the Clone Wars was originally developed as a plot element for The Empire Strikes Back; specifically, that he served as the source for a clone army that eventually became the Empire’s stormtroopers—which contradicts the implication from A New Hope that suggests the stormtroopers were recruited from an Imperial Academy. In J.W. Rinzler’s book The Making of Star Wars, Lucas remarked on the lack of women working for the Empire: “Some of the stormtroopers are women, but there weren’t that many women assigned to the Death Star.” This would seem to contradict the later assertion that stormtroopers are clones. But moreover, it demonstrates that Lucas’ mythology was ever-changing during the creative process. As ideas continued to develop, they shifted away from the singular mythology of A New Hope. In fact, when Brackett turned in her first screenplay draft of Lucas’ treatment in February 1977, there was no mention of Vader being Luke’s father, and The Empire Strikes Back was still considered “Chapter II” in the series. Sadly, Brackett died of cancer the following month.

After Brackett passed, Lucas found himself unhappy with her draft and composed another draft himself, which included the revelation that Luke’s father was Darth Vader. This tied things up quite nicely, as Brackett’s version contained a separate version of “Father Skywalker” who talked to Luke in ghost-form, which Lucas could now excise. During the revision of his second draft and a third draft that he authored, Lucas finally formulated the parallel-laden family history and dramatic arcs between Obi-Wan, Annakin, Luke, Vader, and the Emperor. This change accounts for other incongruities, such as the moment in A New Hope when Obi-Wan tells Luke that Vader betrayed and killed Luke’s father—a point later clarified in Return of the Jedi when Obi-Wan explains, “What I told you was true… from a certain point of view.” These after-the-fact changes to the mythology moved the series away from a Flash Gordon-esque adventure story to a more intricate tradition in the realm of Greek myths or Frank Herbert’s Dune series. Whereas A New Hope felt more like a comic-book come to splendid life, The Empire Strikes Back turned Lucas’ stories into a saga that spans generations. For the first time in the entire franchise, Star Wars earns the label “space opera”.

After Brackett passed, Lucas found himself unhappy with her draft and composed another draft himself, which included the revelation that Luke’s father was Darth Vader. This tied things up quite nicely, as Brackett’s version contained a separate version of “Father Skywalker” who talked to Luke in ghost-form, which Lucas could now excise. During the revision of his second draft and a third draft that he authored, Lucas finally formulated the parallel-laden family history and dramatic arcs between Obi-Wan, Annakin, Luke, Vader, and the Emperor. This change accounts for other incongruities, such as the moment in A New Hope when Obi-Wan tells Luke that Vader betrayed and killed Luke’s father—a point later clarified in Return of the Jedi when Obi-Wan explains, “What I told you was true… from a certain point of view.” These after-the-fact changes to the mythology moved the series away from a Flash Gordon-esque adventure story to a more intricate tradition in the realm of Greek myths or Frank Herbert’s Dune series. Whereas A New Hope felt more like a comic-book come to splendid life, The Empire Strikes Back turned Lucas’ stories into a saga that spans generations. For the first time in the entire franchise, Star Wars earns the label “space opera”.

To direct The Empire Strikes Back Lucas entrusted Irvin Kershner, a former USC classmate-turned-instructor, whom Lucas promised creative freedom. To polish the final drafts, Lucas called upon Kasdan, who had just turned in his script for Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), Lucas’ serial-inspired adventure directed by Steven Spielberg. According to Dave Pollack’s biography Skywalking: The Life and Films of George Lucas, “Kasdan’s main criticism [of Lucas’ The Empire Strikes Back script] was that Lucas glossed over the emotional content of a scene in his hurry to get to the next one.” Indeed, this would become evident in Lucas’ prequel films, which he authored without contribution from other writers. “Well, if we have enough action,” Lucas reasoned in an interview, “no one will notice.” Kasdan soon discovered the essence of a George Lucas-penned scene, that he cares less about characters, their connections to one another, and their distinctive qualities—Lucas writes to drive the plot forward. Kasdan has always been more interested in the relationships between people, as his later directorial efforts The Big Chill (1983) and Silverado (1985) demonstrate. As Kershner oversaw early pre-production and storyboarding, Kasdan finished the final shooting draft in November 1979.

Filming began on March 5, 1979. Kershner, who was not a favored choice by Twentieth Century Fox because of his age (mid-fifties), relied on Lucas’ Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) to provide the special FX know-how, while he concentrated on characters and emotions. All the while, Lucas, serving as executive producer, sought to speed up Kershner’s pace, and Kershner responded with several confrontations about slowing down the increasingly over-budget picture. Lucas remained stressed throughout production because, in wanting to ensure his independence from the studio, he financed The Empire Strikes Back himself. Gary Kurtz, who co-produced Star Wars, once again oversaw production. Kurtz allowed Kershner to take his time and kept Lucas occupied with the visual aspects at ILM. Despite weather troubles, Carrie Fisher’s drug habit, problems with the effects, a burned-down stage, and general misfortunes that caused the shoot to fall behind schedule, Kershner proceeded methodically, concentrating on the end product. Lucas was enraged that Kurtz allowed Kershner so much leeway, but then, had Lucas produced or even directed, he would have taken shortcuts or focused more on visuals than characters. After all, Lucas wanted The Empire Strikes Back to provide him with Skywalker Ranch, not a great sequel. Kershner wanted to make a great film; he may have spent $33 million on a budget of $15 million, requiring Lucas to take out a second and third loan, but in the end, Kershner made a great film. He was the perfectionist storyteller that Lucas would never be. Taking in $209 million at the domestic box-office, The Empire Strikes Back performed extremely well, even if some critics at the time complained that it lacked the escapist, adventurous spirit of the original. Others felt off-put by the cliffhanger conclusion. The dissenters’ tune would change upon reflection, but their evaluations are not without merit.

Filming began on March 5, 1979. Kershner, who was not a favored choice by Twentieth Century Fox because of his age (mid-fifties), relied on Lucas’ Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) to provide the special FX know-how, while he concentrated on characters and emotions. All the while, Lucas, serving as executive producer, sought to speed up Kershner’s pace, and Kershner responded with several confrontations about slowing down the increasingly over-budget picture. Lucas remained stressed throughout production because, in wanting to ensure his independence from the studio, he financed The Empire Strikes Back himself. Gary Kurtz, who co-produced Star Wars, once again oversaw production. Kurtz allowed Kershner to take his time and kept Lucas occupied with the visual aspects at ILM. Despite weather troubles, Carrie Fisher’s drug habit, problems with the effects, a burned-down stage, and general misfortunes that caused the shoot to fall behind schedule, Kershner proceeded methodically, concentrating on the end product. Lucas was enraged that Kurtz allowed Kershner so much leeway, but then, had Lucas produced or even directed, he would have taken shortcuts or focused more on visuals than characters. After all, Lucas wanted The Empire Strikes Back to provide him with Skywalker Ranch, not a great sequel. Kershner wanted to make a great film; he may have spent $33 million on a budget of $15 million, requiring Lucas to take out a second and third loan, but in the end, Kershner made a great film. He was the perfectionist storyteller that Lucas would never be. Taking in $209 million at the domestic box-office, The Empire Strikes Back performed extremely well, even if some critics at the time complained that it lacked the escapist, adventurous spirit of the original. Others felt off-put by the cliffhanger conclusion. The dissenters’ tune would change upon reflection, but their evaluations are not without merit.

Due to offscreen and scripting issues, several aspects about The Empire Strikes Back remain odd or ungainly. Harrison Ford told Lucas during production that he wasn’t interested in participating in another Star Wars film after The Empire Strikes Back. This led to Han’s encasement in carbonite becoming an uncertain end, and the possibility of Lando taking over the “scoundrel” role for Han. In the final shots of The Empire Strikes Back, the audience even sees Lando wearing Han’s signature outfit—an odd moment, without a doubt. There is also the dramatically ham-fisted moment when Luke confronts himself dressed as Darth Vader in a Dagobah cave. Or consider the ineffective reveal of “another hope” for the Rebellion besides Luke. Yoda and Obi Wan’s spirit talk about Luke on Dagobah. Obi-Wan says, “He is our only hope.” Yoda replies, “No… there is another.” This implies Luke is not as significant to the overall story as we believe him to be, or as the story has established thus far. None of these criticisms are meant to discredit the overall effect of The Empire Strikes Back; rather, they suggest that Lucas’ grand design had yet to be written and would remain in flux until each film hit theaters. The reason being, quite simply, is that he kept changing the mythology as he went. Lines of dialogue here offer a contradiction there. Nevertheless, Lucas insisted “This is what I always intended” and, at the time, believed he had another ten films to work out any plot holes. It didn’t work out that way. Today, only in its broadstrokes does the Star Wars saga flow together as a consistent, cohesive melodrama.

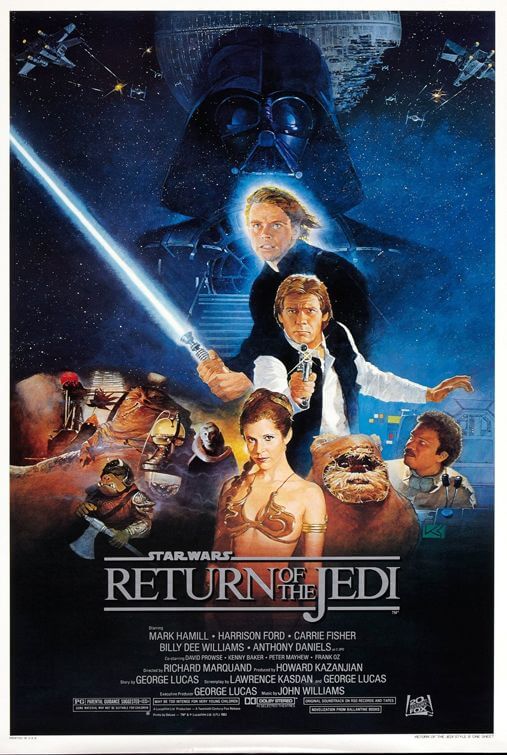

On its own, The Empire Strikes Back relies on what came before and what will follow and proves incomplete as an experience unto itself. Not only incomplete but incongruous. Consuming films in this manner is a pattern that echoes into modern television, where the “just one more” syndrome of binge-watching has overcome the majority of home viewers. Lucas claimed to have a grand design but, not unlike a television series such as Lost, the creator began with a wonderful concept and continued to build upon it, until the final result no longer resembled what was originally so engaging. Though it deviates from Star Wars and the subsequent films don’t quite live up to what it anticipates, The Empire Strikes Back remains the franchise’s most character-centric and emotionally involving entry. This is largely a result of Kasdan and Kershner, two talents who built upon the established mythology to create something more dramatically fulfilling. Return of the Jedi and the prequels would lose themselves in plot machinations, largely because of Lucas’ influence. But here we experience how more meticulous and audience-concerned talent can better shape the material to the viewer’s needs. Ironically, The Empire Strikes Back feels like the most accomplished Star Wars film, even though it’s the most incomplete.

On its own, The Empire Strikes Back relies on what came before and what will follow and proves incomplete as an experience unto itself. Not only incomplete but incongruous. Consuming films in this manner is a pattern that echoes into modern television, where the “just one more” syndrome of binge-watching has overcome the majority of home viewers. Lucas claimed to have a grand design but, not unlike a television series such as Lost, the creator began with a wonderful concept and continued to build upon it, until the final result no longer resembled what was originally so engaging. Though it deviates from Star Wars and the subsequent films don’t quite live up to what it anticipates, The Empire Strikes Back remains the franchise’s most character-centric and emotionally involving entry. This is largely a result of Kasdan and Kershner, two talents who built upon the established mythology to create something more dramatically fulfilling. Return of the Jedi and the prequels would lose themselves in plot machinations, largely because of Lucas’ influence. But here we experience how more meticulous and audience-concerned talent can better shape the material to the viewer’s needs. Ironically, The Empire Strikes Back feels like the most accomplished Star Wars film, even though it’s the most incomplete.

Sources:

Bailey, T. J. Devising a Dream: A Book of Star Wars Facts and Production Timeline. Louisville, KY: Wasteland Press, 2005.

Baxter, John. Mythmaker: The Life and Work of George Lucas (1st ed.). New York: William Morrow, 1999.

Bouzereau, Laurent. Star Wars: The Annotated Screenplays. New York: Del Rey, 1997.

Hearn, Marcus. The Cinema of George Lucas. New York: ABRAMS Books, 2005.

Kaminski, Michael. The Secret History of Star Wars: The Art of Storytelling and the Making of a Modern Epic. Kingston, Ont.: Legacy Books Press, 2008.

Rinzler, J.W. The Making of Star Wars. LucasBooks, 2007.

Sansweet, Stephen (1992). Star Wars: From Concept to Screen to Collectible. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review