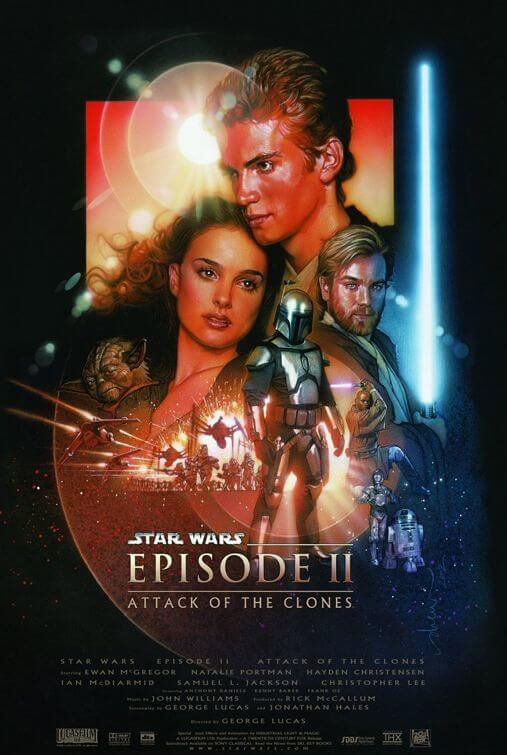

Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones

By Brian Eggert |

Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones takes place on digital worlds, where actors exist independently of the distractingly synthetic CGI spaces they inhabit. The first major blockbuster shot entirely with digital cameras instead of celluloid, the film exists on two visually separate planes: The first plane consists of computer-generated sets, planets, backdrops, and several characters, each of them adorned with glossy computer-animated detail. An incredible assortment of multicultural aliens, flashing signage, beeping droids, and flying ships whiz by before our eyes, rendered with supercomputer technology that was considered top-notch upon the film’s release in 2002. The second plane is the world of George Lucas’ human actors. This is a rigid, inexpressive world, where performers are forced to utter dull, melodramatic dialogue to one another, and hold a wooden presence in their director’s empty, over-plotted storytelling. Here, even their shadows are artificially created. On these disparate planes, Lucas returns us to a galaxy far, far away, but leaves us uninterested and devoid of wonder and emotional connection, if not entirely bored by the experience.

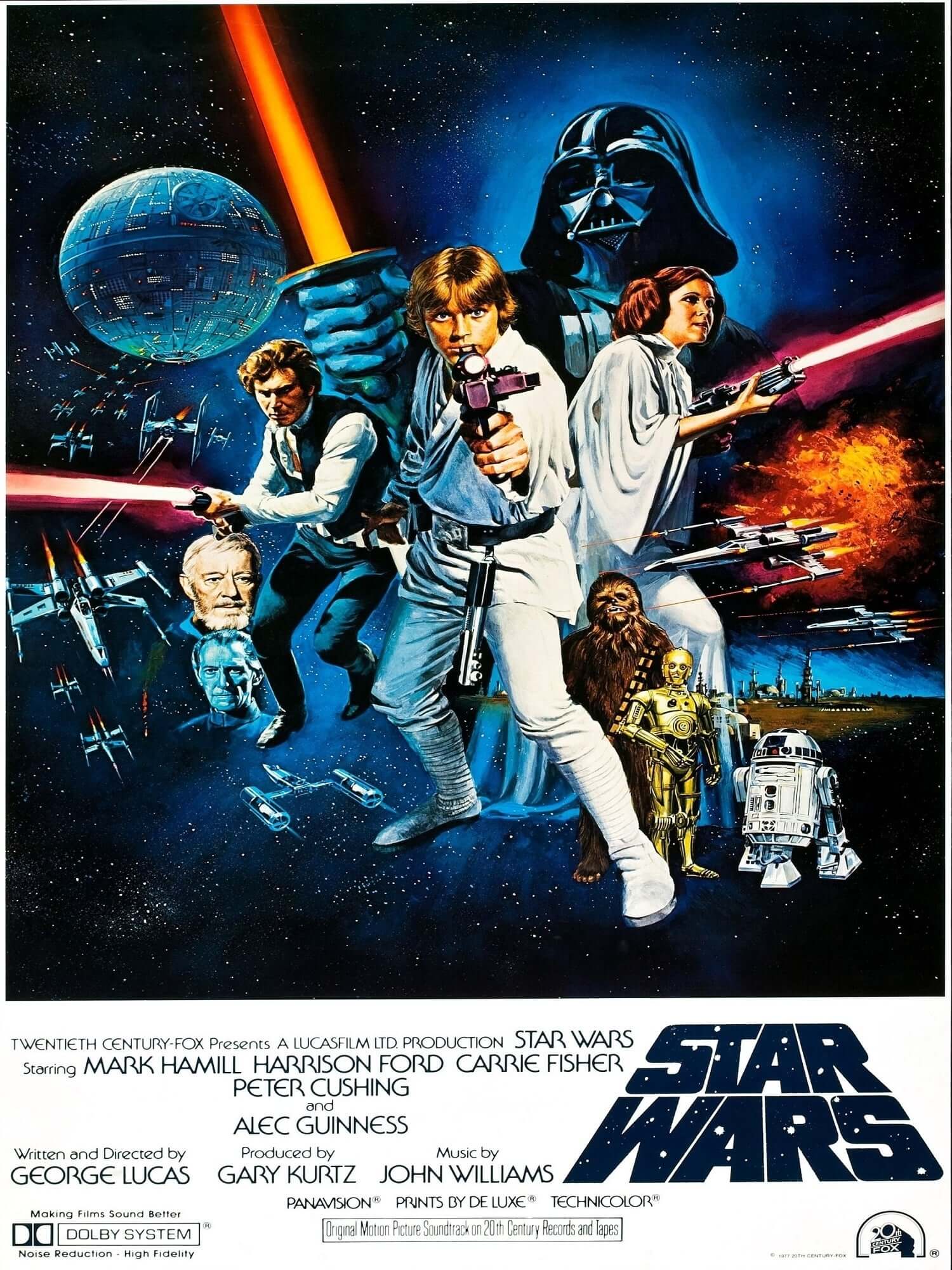

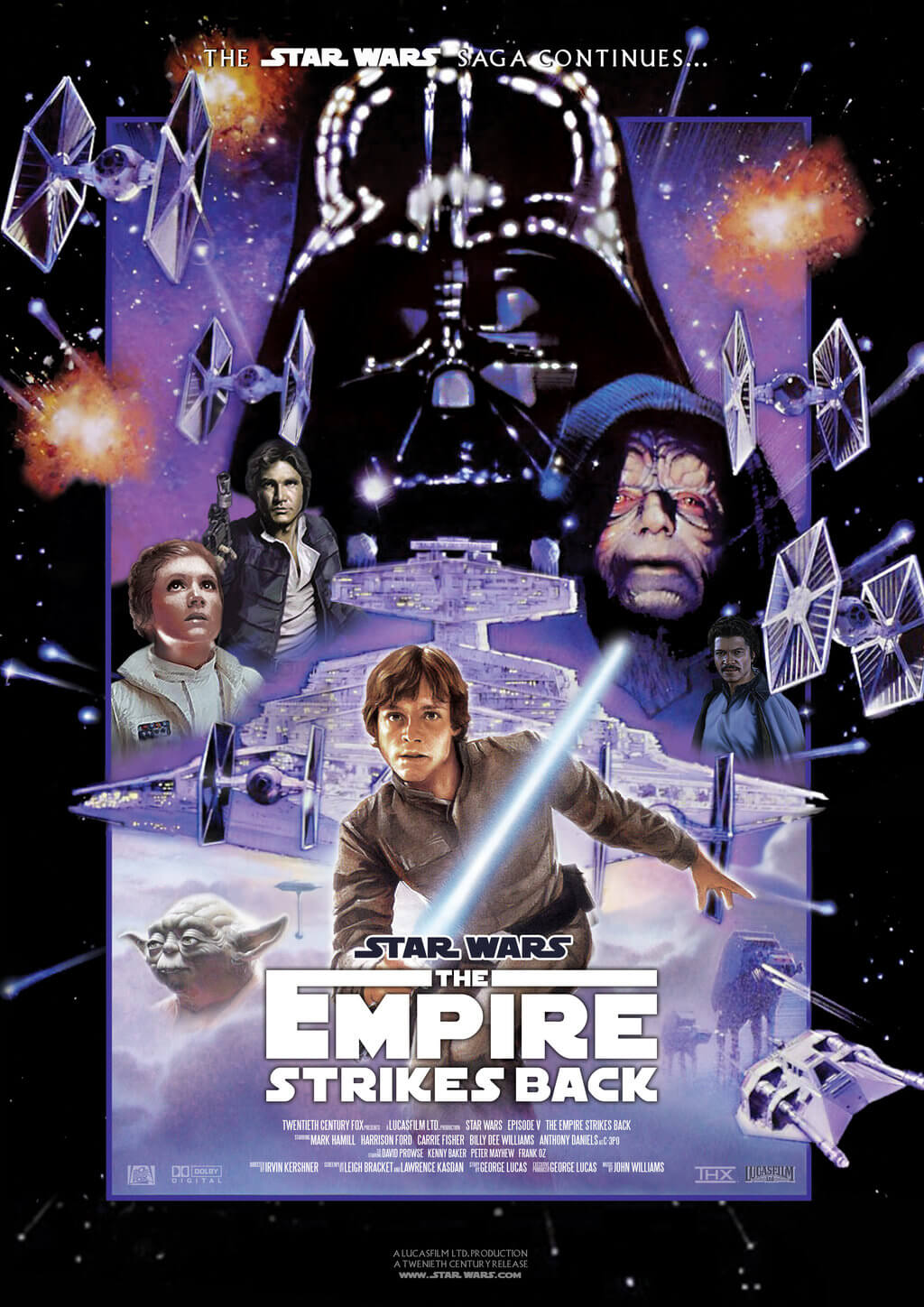

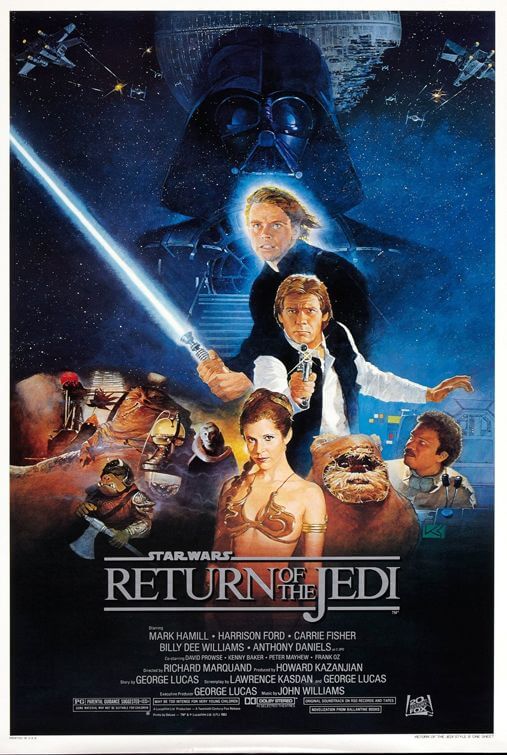

Continuing to demystify his original trilogy just as he had done with The Phantom Menace, writer-director Lucas used Attack of the Clones to answer another set of questions that should have been left unanswered. What were the “Clone Wars” briefly mentioned by Obi-Wan Kenobi in A New Hope? When did the Empire begin building the Death Star? How did Luke Skywalker’s parents fall in love? Lucas offers only unsatisfying answers, such as reducing fan-favorite character Boba Fett into an unaltered clone of his father. In each case, Lucas’ way of clarifying a mystery from the original trilogy spoils our initial fascination, while knowing where most of these characters end up, along with Lucas’ joyless writing, renders the material dramatically lifeless. Having learned nothing from the largely negative responses to The Phantom Menace, Lucas continued to write the story himself, rather than hand the material off to another writer as he had done on The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi. The result was another critical failure and fan disappointment, although one could argue the letdown burned less this time around, since enthusiasm for the prequels had been curbed by the 1999 release.

Admittedly, I have watched Attack of the Clones two or three times, and almost immediately after viewing, all memory of the experience fades. To write the summary of the plot below, not only did I have to take extensive notes during a Blu-ray screening, but I had to rely on official summaries. It’s not that Attack of the Clones is a particularly complex narrative; rather, it’s just that the human brain tends to shut down when it’s not engaged. The entire film plods on and on (and on some more) for well over two hours, leaving almost no impression. Its digital existence recalls an extended videogame cutscene, where the viewer finds themselves waiting for the cutscene to stop so the gameplay can resume, except there’s no controller in our hands, and the cutscene doesn’t end until the closing credits. In fact, several Star Wars videogames have been more engaging on a dramatic level than Attack of the Clones.

Admittedly, I have watched Attack of the Clones two or three times, and almost immediately after viewing, all memory of the experience fades. To write the summary of the plot below, not only did I have to take extensive notes during a Blu-ray screening, but I had to rely on official summaries. It’s not that Attack of the Clones is a particularly complex narrative; rather, it’s just that the human brain tends to shut down when it’s not engaged. The entire film plods on and on (and on some more) for well over two hours, leaving almost no impression. Its digital existence recalls an extended videogame cutscene, where the viewer finds themselves waiting for the cutscene to stop so the gameplay can resume, except there’s no controller in our hands, and the cutscene doesn’t end until the closing credits. In fact, several Star Wars videogames have been more engaging on a dramatic level than Attack of the Clones.

The story involves an increasingly violent separatist movement led by Count Dooku (Christopher Lee) against the Galactic Republic. With the Jedis unable to handle the threat alone, Senator Amidala (Natalie Portman) intends to plea for an army to defend the Republic, but assassination attempts on her life send her into hiding. The Jedis assign the now teenaged and impetuous Jedi-in-training Anakin Skywalkeer (Hayden Christensen) to protect Amidala on Naboo, where they quickly fall in love, while his master Obi-Wan Kenobi (Ewan McGregor) goes searching for the bounty hunter who hired Amidala’s would-be assassin. Obi-Wan finds not only bounty hunter Jango Fett (Temuera Morrison) but a cloned army that was curiously requested by the Republic long ago. Meanwhile, Anakin and Amidala return to Tatooine to find Anakin’s mother, who has since been kidnapped and killed by Tusken Raiders. In retaliation, Anakin hunts down the Raiders and slaughters their entire village. Later, Anakin and Amidala meet up with Obi-Wan at a separatist base, where they fight Dooku, Fett, and their droid army. Joining the fray is a small army of Jedi Knights and their clone army, which drive off the separatists. Mace Windu (Samuel L. Jackson) kills Jango Fett. Dooku chops off Anakin’s arm. Yoda fights off Dooku, who escapes. But it’s all part of the plan, according to Ian McDiarmid’s mysterious Darth Sidious. Despite the downer conclusion alluding to a Clone War, the final shot shows a robot-armed Anakin marrying Amidala.

Lucas’ script carries on using an incredible number of clichés, corny dialogue, and just-plain-bad storytelling. Consider the “I hate it when he does that”-type banter between Anakin and Obi-Wan. Or the eye-rollingly dumb way Obi-Wan says to Anakin, “Why do I get the feeling you’re going to be the death of me?”—which makes light of Obi-Wan’s death in A New Hope. Lucas’ characters also speak in bad action movie comebacks, such as Jackson’s Mace Windu, along with several other characters who say, “I don’t think so” when faced with an opposition. The exchanges between Anakin and Amidala are particularly graceless and inconsistent. One minute she’s saying Anakin will always be that little boy from Tatooine, the next minute they’re rolling in the grass in a scene ripped from daytime television, where Anakin declares his feelings in verses of bad teenage poetry (“I’m haunted by the kiss that you should never have given me. My heart is beating, hoping that kiss will not become a scar. You are in my very soul, tormenting me.”). Elsewhere, there’s a great (intentional?) irony as the annoying Jar Jar Binks, now acting as Senator, agrees to place Palpatine in charge as Chancellor—much the equivalent of Adolf Hitler in post-World War I Germany. And like Hitler, the Chancellor becomes a genocidal dictator, Darth Sidious. And so, if we didn’t already have reason enough to hate Jar Jar, add electing Hitler to the list.

Lucas’ script carries on using an incredible number of clichés, corny dialogue, and just-plain-bad storytelling. Consider the “I hate it when he does that”-type banter between Anakin and Obi-Wan. Or the eye-rollingly dumb way Obi-Wan says to Anakin, “Why do I get the feeling you’re going to be the death of me?”—which makes light of Obi-Wan’s death in A New Hope. Lucas’ characters also speak in bad action movie comebacks, such as Jackson’s Mace Windu, along with several other characters who say, “I don’t think so” when faced with an opposition. The exchanges between Anakin and Amidala are particularly graceless and inconsistent. One minute she’s saying Anakin will always be that little boy from Tatooine, the next minute they’re rolling in the grass in a scene ripped from daytime television, where Anakin declares his feelings in verses of bad teenage poetry (“I’m haunted by the kiss that you should never have given me. My heart is beating, hoping that kiss will not become a scar. You are in my very soul, tormenting me.”). Elsewhere, there’s a great (intentional?) irony as the annoying Jar Jar Binks, now acting as Senator, agrees to place Palpatine in charge as Chancellor—much the equivalent of Adolf Hitler in post-World War I Germany. And like Hitler, the Chancellor becomes a genocidal dictator, Darth Sidious. And so, if we didn’t already have reason enough to hate Jar Jar, add electing Hitler to the list.

Beyond Lucas’ script playing out like bad Star Wars fan-fiction, his choice of actors remains a sore spot for many a devoted fan. Portman, Jackson, and McGregor continue their rather impassive turns, reading their lines with an astounding woodenness. But Lucas achieved another cinematic crime altogether by casting Hayden Christensen as Anakin. Christensen plays Anakin with the worst case of Terrible Teens you’re ever bound to see, angsty and unstable. He’s also quite creepy, sometimes unintentionally so, and we cannot help but wonder what Amidala sees in him. To be sure, it’s difficult to look at Christensen’s performance here and not get a rapey vibe, or suspect that at some point he’s going to shoot up a school. (NOTE: In Revenge of the Sith, Anakin carries out the Star Wars equivalent of a school shooting when he light sabers an entire Jedi class to death.) The problem is not entirely Christensen’s fault, however; Lucas has written Anakin so that he isn’t likable in the least. He’s a terrible student; he whines incessantly; he’s impatient, disobedient, sarcastic, and prone to emotional outbursts. He holds an unjustified animosity toward Obi-Wan for holding him back. And he’s also a killer, slaughtering an entire tribe of Tusken Raiders, including women and children, without setting off any major alarms for Amidala. And rather than react to his confession of mass murder, Amidala does what she usually does, stands there with a blank expression, then says “I do.”

Even the presentation is flat and lifeless. After the release of The Phantom Menace, Lucas felt celluloid was “cumbersome”, and driven to save the cost of converting celluloid to digital for editing and integration of special FX at Industrial Light & Magic, Lucas was determined to shoot Attack of the Clones entirely on digital. Since the 1980s, film stock was commonly scanned and edited digitally to speed up the process; but digital cameras would create further efficiencies in the filming process, making it easier and less costly. Without having to worry about lighting setups or cleaning tears and dust on the film stock—which could easily be corrected in post-production using computers—digital cameras would allow for faster shoots. Lucas contacted Sony and asked them to build him a digital camera that would shoot in high-definition, and in a collaboration with Panavision, Sony delivered the HDW-F900—a camera even Sony representatives later said was “not designed like a film camera”. Lucas had all but proclaimed the Digital Age had begun, that the future of filmmaking was not celluloid but digital cameras, memory drives, and faster production times. For Lucas, the visible grain and texture of film stock was an acceptable sacrifice for the convenience of digital, whereas much of the film industry voiced (and still voice) their disdain for the abandonment of celluloid.

Even the presentation is flat and lifeless. After the release of The Phantom Menace, Lucas felt celluloid was “cumbersome”, and driven to save the cost of converting celluloid to digital for editing and integration of special FX at Industrial Light & Magic, Lucas was determined to shoot Attack of the Clones entirely on digital. Since the 1980s, film stock was commonly scanned and edited digitally to speed up the process; but digital cameras would create further efficiencies in the filming process, making it easier and less costly. Without having to worry about lighting setups or cleaning tears and dust on the film stock—which could easily be corrected in post-production using computers—digital cameras would allow for faster shoots. Lucas contacted Sony and asked them to build him a digital camera that would shoot in high-definition, and in a collaboration with Panavision, Sony delivered the HDW-F900—a camera even Sony representatives later said was “not designed like a film camera”. Lucas had all but proclaimed the Digital Age had begun, that the future of filmmaking was not celluloid but digital cameras, memory drives, and faster production times. For Lucas, the visible grain and texture of film stock was an acceptable sacrifice for the convenience of digital, whereas much of the film industry voiced (and still voice) their disdain for the abandonment of celluloid.

With this innovative method, Lucas could make Attack of the Clones in a different way than any of its predecessors; but this also means that the film doesn’t look like the other Star Wars films, especially because Lucas chose not to thoroughly experiment with the new digital cameras in a test project. Nevertheless, the method allowed for a number of efficiencies. The production required few actual sets to be built; only a few real-life locations were used and supplemented with CGI. Scenes could be filmed in big green and blue rooms, their backgrounds, lighting effects, and details filled-in during post-production. The directorial strain on Lucas, which had caused him to not direct The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi years before, was virtually gone. Rather than spend time creating tangible puppets for characters like Yoda, ILM could animate them. But they were created with animation that even Pixar had bettered by that point. Indeed, Pixar’s release Monsters, Inc. from the year before boasted three-dimensional looking characters, complete with lifelike hair and the illusion of impressive physical depth. There’s nothing realistic about a cartoonish, videogame-like Yoda bouncing around the screen like Sonic the Hedgehog in a pinball machine, nor the animated shadows painted beneath actors who seem separate from the world around them. Worse, many of Lucas’ designs are kitschy and uninspired; the long-necked aliens on the planet Kamino look like rejects from Steven Spielberg’s A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001), whereas the back-to-the-fifties diner (complete with snappy robo-waitresses and a four-armed, mustached fry cook) couldn’t be less inspired.

Because of the subpar animation, and also because of the new digital camera’s limitations, the entire film exists on flat planes, without depth. Then again, so does the story. Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones spearheaded Lucas’ Digital Revolution and began an industry movement that would forever change how films look and are made—though, arguably, this industrywide development served only the filmmakers, not the audience. No matter the moviegoer’s position on digital filmmaking as it stands today, this first major implementation comes with an underwhelming and unpolished presentation, where the viewer’s immersion is prevented by Lucas’ one-dimensional, simulated world. The entire experience feels drained of energy and vision, and feels more like a computer program run wild than a filmmaker’s fully realized world. Never has watching clones fight robots, or looking at an expansive metropolis been so dull. Lucas’ digital approach should have been perfected in another arena, not in the midst of an ongoing franchise. But no amount of technical wizardry could have improved the film enough to make his lackluster storytelling or flat drama tolerable. Only small children or a Star Wars apologist of the highest order could find this half-hearted treatment bearable, while it takes another level of enthusiast altogether to actually identify its redeemable qualities, if any exist. This critic has difficulty identifying them.

Because of the subpar animation, and also because of the new digital camera’s limitations, the entire film exists on flat planes, without depth. Then again, so does the story. Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones spearheaded Lucas’ Digital Revolution and began an industry movement that would forever change how films look and are made—though, arguably, this industrywide development served only the filmmakers, not the audience. No matter the moviegoer’s position on digital filmmaking as it stands today, this first major implementation comes with an underwhelming and unpolished presentation, where the viewer’s immersion is prevented by Lucas’ one-dimensional, simulated world. The entire experience feels drained of energy and vision, and feels more like a computer program run wild than a filmmaker’s fully realized world. Never has watching clones fight robots, or looking at an expansive metropolis been so dull. Lucas’ digital approach should have been perfected in another arena, not in the midst of an ongoing franchise. But no amount of technical wizardry could have improved the film enough to make his lackluster storytelling or flat drama tolerable. Only small children or a Star Wars apologist of the highest order could find this half-hearted treatment bearable, while it takes another level of enthusiast altogether to actually identify its redeemable qualities, if any exist. This critic has difficulty identifying them.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review