Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace

By Brian Eggert |

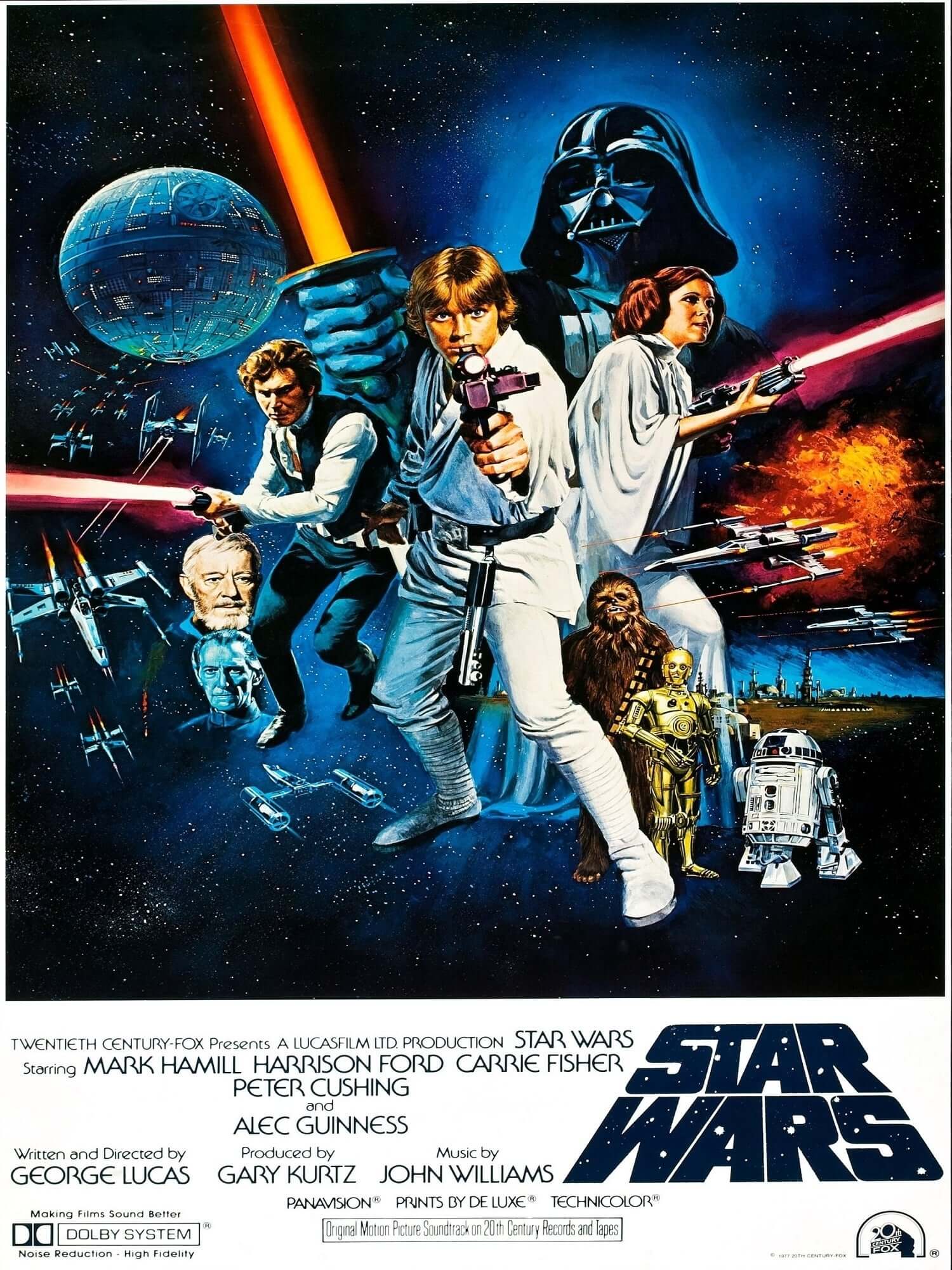

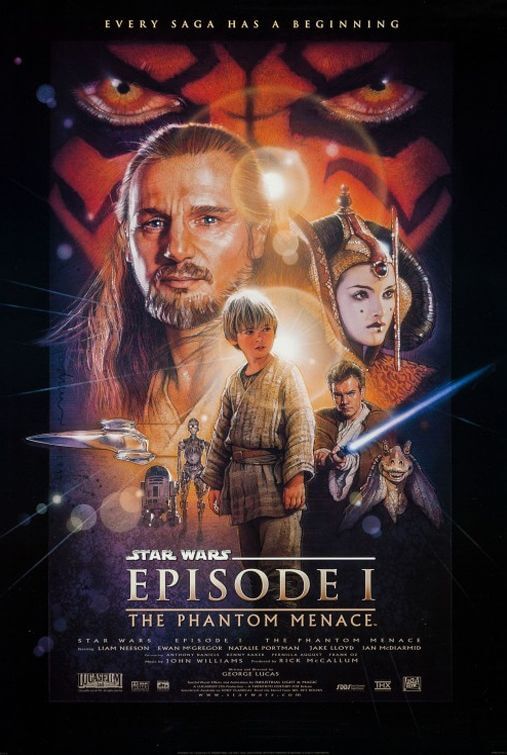

Standing in line for Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace in the early summer movie season of 1999, fans were full of unchecked anticipation, many camping out to ensure their spot in line during the days before pre-ordering tickets and reserving seats. Do you remember how optimistic you felt toward The Phantom Menace then? It was almost as though the latest chapter in the Star Wars saga couldn’t possibly be anything less than great. Indeed, the first trailers looked amazing and showed us brief glimpses of awesomeness: A two-sided light saber held by a mysterious, dark figure with a painted face. Droid armies lining up on a grassy field. Natalie Portman’s makeup-heavy character spouting lines of political intrigue. Ewan McGregor affecting his best Alec Guinness. How could it be anything less than an instant classic? And when the film finally started, John Williams’ iconic score boomed in our ears, those yellow scrolling titles lit up our eyes, and it felt very much like returning to a warm cinematic home after a 16-year winter. Then, as the film went on, we kept waiting for its greatness to begin. We waited and waited. By the time it was over, we left the theater with a strange, unanticipated sensation: disappointment. Disappointment led to anger, anger led to hate, hate led to, well, you get the idea. In the years since The Phantom Menace’s debut, this critic has tried and tried to revisit and reassess, hoping to find that my own unreasonable expectations were to blame for disliking, if not despising this film. But no amount of time or reconsideration is going to change that Lucas’ film is poorly written, hollow, and often offensively bad.

The Phantom Menace set out to accomplish two goals: 1) Make money, 2) Demystify and elaborate upon the mythology of the original Star Wars trilogy, revealing origins to a franchise that, for better or worse, reshaped popular culture and Hollywood forevermore. Along with the two other entries in George Lucas’ prequel trilogy, The Phantom Menace draws its story from the existing trilogy, maneuvering to fill in the blanks and answer every question that audiences were otherwise content to leave unknown. Aside from a handful of interesting ideas and diverting moments, the film relies on our devotion to and familiarity with the originals to propel its plot, without which it would be an inexcusable experience. To be sure, the viewer’s love of the Star Wars universe will invariably tame their loathing of The Phantom Menace, and often leads to an apologist’s point of view (such as, “It’s not that bad.” But it is.). In reality, it’s a money machine, more developed and executed to further a billion dollar franchise and explore the limits of digital wizardry, as opposed to satisfying a need to explore narrative strains that its filmmaker felt a creative urge to express. While the result accomplished its monumental box-office goals, any hope of true satisfaction over the storytelling or filmmaking remains impossible, as the outcome is an inert experience devoid of the passion and magic that made the original trilogy such a wonder.

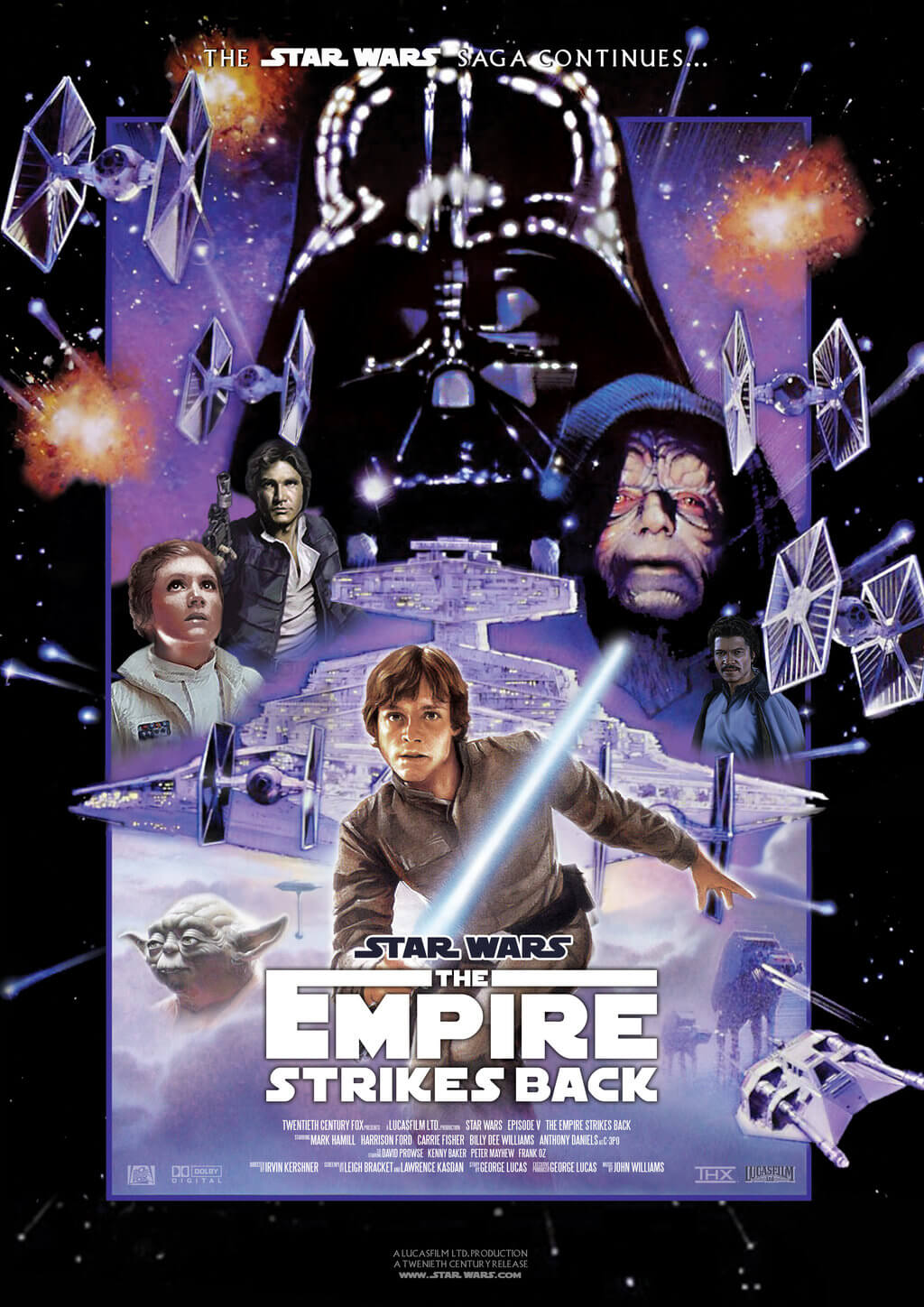

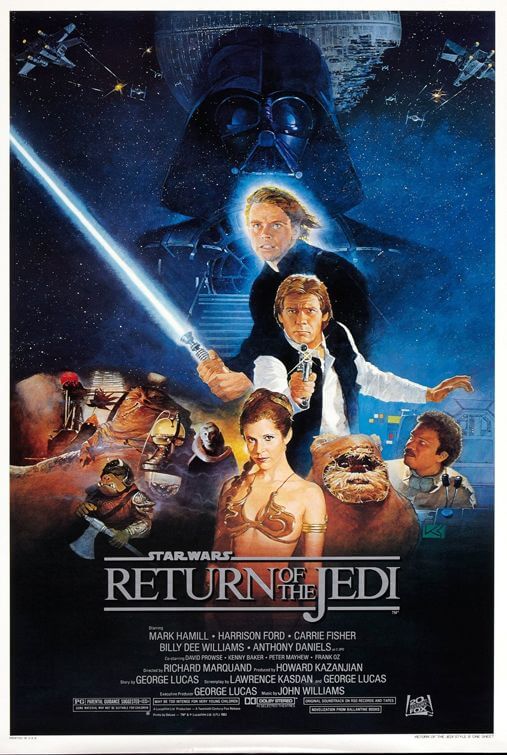

Hollywood is obsessed with the idea of demystification through prequels; after all, they have a built-in market that wants to revisit a well-known property. Titles like Oz the Great and Powerful (2013), Prometheus (2012), and The Thing (2011) sought to elaborate on the mythologies of their respective originals, until every plot point has been extended and exploited. However, prequels usually leave moviegoers remembering how remarkable the originals were and shrugging over the mediocre new material. George Lucas may not have invented the idea of a prequel, but The Phantom Menace, Attack of the Clones, and Revenge of the Sith popularized it. Prequels in general seem to exist not because the story demands it, but rather because the financial possibilities of exploiting a known franchise are too substantial to ignore—this is true of the Star Wars prequels more than most. Lucas’ prequels answer questions that do not need answering; they fill in blanks that did not need to be filled; they add thin layers to a franchise that was already an unshakable legacy. Worse, because the audience knows where the main characters end up, as we have already seen their fates in the originals, any hope for immersive dramatic involvement is next to impossible. Perhaps this is why The Phantom Menace and the subsequent prequels feel so dead-on-arrival.

Hollywood is obsessed with the idea of demystification through prequels; after all, they have a built-in market that wants to revisit a well-known property. Titles like Oz the Great and Powerful (2013), Prometheus (2012), and The Thing (2011) sought to elaborate on the mythologies of their respective originals, until every plot point has been extended and exploited. However, prequels usually leave moviegoers remembering how remarkable the originals were and shrugging over the mediocre new material. George Lucas may not have invented the idea of a prequel, but The Phantom Menace, Attack of the Clones, and Revenge of the Sith popularized it. Prequels in general seem to exist not because the story demands it, but rather because the financial possibilities of exploiting a known franchise are too substantial to ignore—this is true of the Star Wars prequels more than most. Lucas’ prequels answer questions that do not need answering; they fill in blanks that did not need to be filled; they add thin layers to a franchise that was already an unshakable legacy. Worse, because the audience knows where the main characters end up, as we have already seen their fates in the originals, any hope for immersive dramatic involvement is next to impossible. Perhaps this is why The Phantom Menace and the subsequent prequels feel so dead-on-arrival.

The story involves trade routes on the planet Naboo that are blocked by the Trade Federation in a dispute over taxation. Two Jedis, master Qui-Gon Jinn (Liam Neeson) and his young apprentice Obi-Wan Kenobi (McGregor), investigate and uncover the beginnings of a conspiracy to invade Naboo. The Jedis rescue Naboo’s Queen Amidala (Portman) and escape to Tatooine, where their ship requires parts for repair. There, they befriend nine-year-old slave Anakin Skywalker (Jake Lloyd), a so-called “chosen one” whose power over The Force is off the scale. After developing a crush on Amidala, who’s old enough to be his mother, Anakin agrees to participate in a Pod-racer tournament to win his new friends the means to leave Tatooine. He wins, of course, and earns his own freedom as well, leaving his slave mother behind. They leave to plead their case with the Galactic Senate after narrowly escaping an attack by Darth Maul (Ray Park), who was sent by Darth Sidious (Ian McDiarmid)—Naboo’s ally Senator Palpatine in disguise. But Amidala’s pleas to the senate prove fruitless, so they return to Naboo to fight back. Despite Qui-Gon being killed by Darth Maul, who is then killed by Obi-Wan, Naboo is victorious. In the end, Obi-Wan takes on Anakin as a Jedi apprentice against the recommendation of the Jedi Council, Palpatine is made Chancellor, and Naboo is safe.

Through the course of complex plotting, Lucas clarifies several ambiguities from the original trilogy in unsatisfactory fashion. In his hands, most characters and major plot turns become mere coincidences that reach into ideas established in Episodes IV-VI. Overall, as the title indicates, The Phantom Menace provides an origin story of how Palpatine gained control and would later become the evil Emperor. Elsewhere, Lucas elaborates on what drives The Force, once explained as a mystical presence in the universe; now, Lucas clarifies that The Force relies on traceable Midichlorians, what Qui-Gon Jinn describes as “microscopic life-forms that reside within the cells of all living things”—making the Force a mystical one that relies on a biological interface. Moreover, Lucas shows us how R2-D2 was originally a droid in service of Queen Amidala, and how C-3PO was Anakin’s unfinished pet project. He plants the seed of romance, however awkward, between Amidala and Anakin, which will eventually lead to the birth of Luke and Leia Skywalker. And he hints that Anakin, who is prophesied to bring balance to The Force and was conceived of a virgin birth (Darth Jesus?), is susceptible to the Dark Side, suggesting how Anakin becomes Darth Vader. It’s all very predictable, barren of surprise or revelation, and more an experience of plot illuminations than raw discovery.

Through the course of complex plotting, Lucas clarifies several ambiguities from the original trilogy in unsatisfactory fashion. In his hands, most characters and major plot turns become mere coincidences that reach into ideas established in Episodes IV-VI. Overall, as the title indicates, The Phantom Menace provides an origin story of how Palpatine gained control and would later become the evil Emperor. Elsewhere, Lucas elaborates on what drives The Force, once explained as a mystical presence in the universe; now, Lucas clarifies that The Force relies on traceable Midichlorians, what Qui-Gon Jinn describes as “microscopic life-forms that reside within the cells of all living things”—making the Force a mystical one that relies on a biological interface. Moreover, Lucas shows us how R2-D2 was originally a droid in service of Queen Amidala, and how C-3PO was Anakin’s unfinished pet project. He plants the seed of romance, however awkward, between Amidala and Anakin, which will eventually lead to the birth of Luke and Leia Skywalker. And he hints that Anakin, who is prophesied to bring balance to The Force and was conceived of a virgin birth (Darth Jesus?), is susceptible to the Dark Side, suggesting how Anakin becomes Darth Vader. It’s all very predictable, barren of surprise or revelation, and more an experience of plot illuminations than raw discovery.

Still, The Phantom Menace has a lot of promise, but it realizes that promise with nothing more than half-explored concepts and emotionless story arcs. Take Darth Maul for example. The foreboding, devil-faced Sith warrior who looks like a Kabuki ghost is a character full of unrealized potential. He’ll forever remain unrealized, however, because Lucas resolves to take the most interesting villain in the film and kill him off quite unceremoniously. During that same battle, Lucas kills off another fascinating character, Qui-Gon Jin, whose relationship with Obi-Wan Kenobi is one-dimensional at best. While he serves as a parallel to how Obi-Wan died at the end of A New Hope, Qui-Gon Jin is yet another character who leaves before the audience has ample time to become attached. Lucas’ script, not to mention his casting choices, also lack personality and emotion. Queen Amidala has such an aloof, flat personality, whereas stiff actor Jake Lloyd struggles to deliver natural lines, even for a child actor. The dialogue is clichéd and unmemorable, and there are no punchy, sarcastic characters worthy of Han Solo, nor anyone with the charm of a Wookie. Much as his collaborators on the original trilogy had criticized, Lucas is far more interested in plot machinations than nuanced characters.

Lucas’ idea of comic relief and charm is Jar Jar Binks, a ceaselessly obnoxious character badly rendered with CGI, who delivers lines like “How rude” (Was Lucas a fan of Kimmy Gibbler?) and “Exsqueeze me?” (And Wayne’s World too?). Generally considered one of cinema’s worst characters in history, Jar Jar represents Lucas’ cutesy petition to children to buy more toys and further the director’s merchandising empire. Jar Jar also represents another trend in The Phantom Menace—the curious stereotyping of certain earthbound races into alien species. Jar Jar looks like a dreadlocked Jamaican with his floppy ears, whereas his Gungan species, headed by a rotund tribal leader, seem like an outdated view of African tribes. Elsewhere, the salamander-esque Trade Federation aliens talk like East Asian stereotypes, plotting and corrupt businessmen. Perhaps worst of all is Watto, Anakin’s slaveowner and shrewd barterer, who shares more than a few similarities to many Jewish stereotypes.

Lucas’ idea of comic relief and charm is Jar Jar Binks, a ceaselessly obnoxious character badly rendered with CGI, who delivers lines like “How rude” (Was Lucas a fan of Kimmy Gibbler?) and “Exsqueeze me?” (And Wayne’s World too?). Generally considered one of cinema’s worst characters in history, Jar Jar represents Lucas’ cutesy petition to children to buy more toys and further the director’s merchandising empire. Jar Jar also represents another trend in The Phantom Menace—the curious stereotyping of certain earthbound races into alien species. Jar Jar looks like a dreadlocked Jamaican with his floppy ears, whereas his Gungan species, headed by a rotund tribal leader, seem like an outdated view of African tribes. Elsewhere, the salamander-esque Trade Federation aliens talk like East Asian stereotypes, plotting and corrupt businessmen. Perhaps worst of all is Watto, Anakin’s slaveowner and shrewd barterer, who shares more than a few similarities to many Jewish stereotypes.

Lucas claims he conceived The Phantom Menace when he first thought up the storyline for Star Wars. More likely, it was after Star Wars debuted in theaters in 1977 and proved to be a monumental box-office hit (probably around the time he renamed it Episode IV: A New Hope). Whether Lucas had the full story for The Phantom Menace in the 1970s, or just saw and took his chance in the 1990s to make a surefire hit, matters not. With a bigger budget and the possibility of CGI-created worlds and characters thanks to trailblazing films like Jurassic Park (1993), Lucas saw no limit to what he could do, and therefore put no limit on himself. As a result, one might posit that, as Lucas obsessed over digital and superficial details—such as hiding Easter Eggs like the aliens from E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial in the senate sequence—he forgot about the importance of telling a good story. It’s about more than plot, Mr. Lucas; it’s also about characters and their personalities. Sadly, the film’s computerized special FX appear dated and artificial today, more so than the timeless, tactile effects in his original trilogy. His CGI characters look like cartoons and the real actors are clearly standing in front of greenscreens. While underwhelming at the time of its release, The Phantom Menace has aged even worse.

Lucas’ prequel was one of the most anticipated films of 1999 and one of that year’s top earners, bringing in $431 million to become the second most successful film ever made, after Titanic (1997). That’s the power of hype. And while more detailed analyses can and have picked apart the film to a far more punishing and comprehensive degree than this assessment, my main arguments against The Phantom Menace remain today what they were in 1999. By demystifying the original films, Lucas does not so much expand on his original mythology but fills in blanks and answers questions that once enchanted us with their mystifying qualities. Lucas extinguishes that enchantment and, in doing so, weakens the original trilogy by association. This is pathetic, albeit expensive filmmaking that relies on unimpressive special FX, dispassionate writing, and an in-built fanbase to make apologies for it. Lucas engages in a troubling Hollywood trend that he helped popularize: prequels. He established the vast bankability of prequel logic as a business model, rather than one of imagination and creativity. The Phantom Menace does not fly us to a galaxy far, far away; but it makes us remember our other journeys to that galaxy. Perhaps that’s the best part of this film. If we can block out the influence of The Phantom Menace on the original trilogy, we might still lovingly remember the originals after this half-hearted, ill-conceived commercial-of-a-movie.

Lucas’ prequel was one of the most anticipated films of 1999 and one of that year’s top earners, bringing in $431 million to become the second most successful film ever made, after Titanic (1997). That’s the power of hype. And while more detailed analyses can and have picked apart the film to a far more punishing and comprehensive degree than this assessment, my main arguments against The Phantom Menace remain today what they were in 1999. By demystifying the original films, Lucas does not so much expand on his original mythology but fills in blanks and answers questions that once enchanted us with their mystifying qualities. Lucas extinguishes that enchantment and, in doing so, weakens the original trilogy by association. This is pathetic, albeit expensive filmmaking that relies on unimpressive special FX, dispassionate writing, and an in-built fanbase to make apologies for it. Lucas engages in a troubling Hollywood trend that he helped popularize: prequels. He established the vast bankability of prequel logic as a business model, rather than one of imagination and creativity. The Phantom Menace does not fly us to a galaxy far, far away; but it makes us remember our other journeys to that galaxy. Perhaps that’s the best part of this film. If we can block out the influence of The Phantom Menace on the original trilogy, we might still lovingly remember the originals after this half-hearted, ill-conceived commercial-of-a-movie.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review