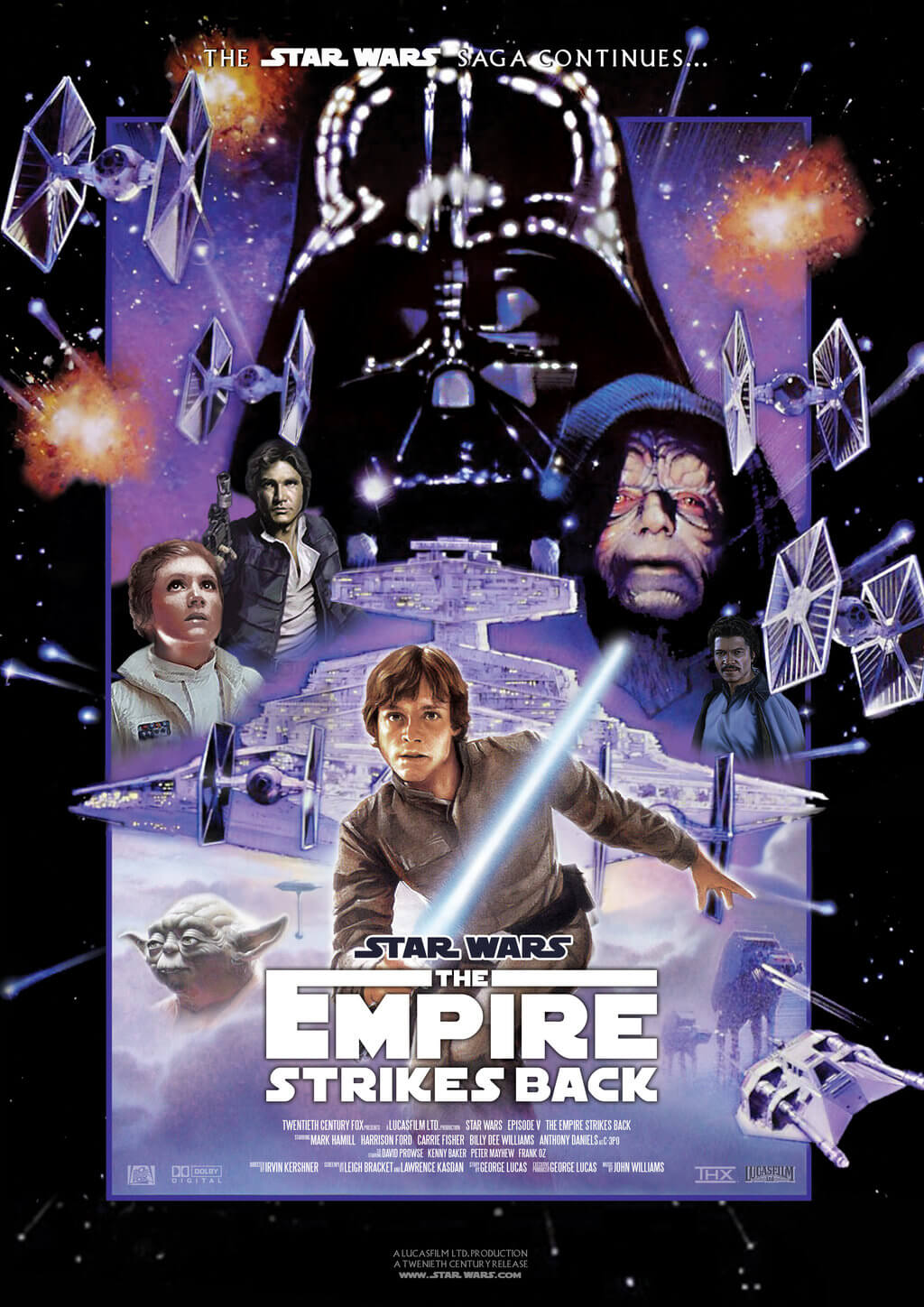

Star Trek V: The Final Frontier

By Brian Eggert |

In the 1989 book Captain’s Log: William Shatner’s Personal Account of the Making of Star Trek V: The Final Frontier, author Lisbeth Shatner, William’s daughter, quotes her father as saying, “Star Trek V is the epitome of my career, my experiences, my hopes and dreams. It is the quintessential me.” The first and only Star Trek feature helmed by the show’s original captain, Star Trek V: The Final Frontier contains mountain climbing, campfire talk of flatulence, anti-gravity jet boots, bareback horse riding, hammy humor throughout, and, finally, the Enterprise crew, specifically Captain Kirk, exposing God as just a mind-controlling alien at the center of our galaxy. The result, like Shatner, is an energetic and lively entry in the Star Trek franchise; however, its estimation of its own profundity proves outlandish. If the film epitomizes what it means to be William Shatner, The Final Frontier offers a frightening look into the ego of an actor who writes and directs himself as the man who proves God does not exist—at least, not in the form in which so many believe.

Indeed, if countless behind-the-scenes stories are to be believed, Shatner held a ferocious sense of professional competition with costar Leonard Nimoy, ever since the original Star Trek series aired from 1966-1969. This competition went so far as Shatner demanding a clause in their contracts that required equal perks between himself and Nimoy. In other words, if Nimoy could direct a Star Trek feature, so could Shatner. Sure enough, after Nimoy directed The Search for Spock and The Voyage Home with surprising depth and narrative finesse, Shatner placed his bid on the fifth film in the Star Trek franchise, insisting on a story of his own devising, just as his costar had done. However, beyond some episodes of his hero cop series T.J. Hooker (1982-1986), Shatner was entirely inexperienced behind the camera, and production reports claim he played the “appease the star” card to earn his director’s chair. Working from his own scenario, Shatner captained the worst film in the ongoing series.

Shatner conceived the basic concept—inspired by watching television evangelists work their faux magic—during the production of The Voyage Home, and admittedly, his idea has merits. Beyond the stupidity of how the story plays out, finding God at the edge of the universe (ahem, galaxy) has been a recurring science-fiction narrative, explored in material best left not to Shatner but to authors like Philip K. Dick and Arthur C. Clarke. To be sure, The Motion Picture dealt with similar themes, where the Enterprise crew investigates a wondrous, unknown, godlike entity only to discover the answer is something simple and sorta unimpressive. In The Final Frontier, any sense of philosophical examination to elevate the subject is trumped by Shatner’s insistence on cornball action and an otherwise glib tone to the proceedings, not to mention the underwhelming special FX. Shatner developed his concept with Harve Bennett (producer of the three previous Star Trek films), and Dreamscape (1984) writer David Loughery. Loughery penned the shooting script.

Shatner conceived the basic concept—inspired by watching television evangelists work their faux magic—during the production of The Voyage Home, and admittedly, his idea has merits. Beyond the stupidity of how the story plays out, finding God at the edge of the universe (ahem, galaxy) has been a recurring science-fiction narrative, explored in material best left not to Shatner but to authors like Philip K. Dick and Arthur C. Clarke. To be sure, The Motion Picture dealt with similar themes, where the Enterprise crew investigates a wondrous, unknown, godlike entity only to discover the answer is something simple and sorta unimpressive. In The Final Frontier, any sense of philosophical examination to elevate the subject is trumped by Shatner’s insistence on cornball action and an otherwise glib tone to the proceedings, not to mention the underwhelming special FX. Shatner developed his concept with Harve Bennett (producer of the three previous Star Trek films), and Dreamscape (1984) writer David Loughery. Loughery penned the shooting script.

The story begins with the Enterprise crew on shore leave in Yosemite National Park, where Kirk, Spock, and McCoy camp their space troubles away, (there’s nothing more un-Star Trek than Spock eating baked beans and singing “Row, Row, Row Your Boat”), while Scotty oversees refurbishments on the new Enterprise. Unending banter propels the first twenty minutes until the crew is called to save some hostages on the desert planet of Nimbus III, held captive by an emotion-crazed Vulcan named Sybok (Laurence Luckinbill), who uses love (and psychic powers) to brainwash people into becoming his followers. Sybok has kidnapped a group of dignitaries and demands a starship as ransom. Once onboard the Enterprise, he turns the crew into “believers” by taking away their psychic pain, reducing everyone to sappy joy drones except Kirk and Spock (who else?), who ignore or rely on their pain for strength. A brainwashed McCoy stays with them because that’s what the audience wants. With Kirk, Spock, and McCoy thrown in the brig, Sybok plans to fly the Enterprise into The Great Barrier—the center of the galaxy where no “man” has gone before. Meanwhile, a Kirk-hating Klingon ship hunting the Enterprise plots an attack for no particular reason whatsoever.

Questions: Why is the Enterprise always the nearest starship to these galactic troubles? There’s never another ship in the quadrant to help out, which leads me to believe that whoever oversees coverage at Starfleet isn’t doing their job. Moreover, the original crew’s Enterprise never seems ready for space travel; it’s always running in a state of disrepair with only a skeleton crew, giving Scotty a mild heart attack in the process. Also, why are the planetary systems always given curious names like Nimbus, Daled, and so forth? Spanning countless languages across the galaxy, there must be enough proper and improper nouns to mix up the naming conventions a little, even if we have to start naming planets after random objects like Kitten or Snowshoe. And how does the Enterprise get to the center of the galaxy so fast? Based on reports from other shows (The Next Generation, Deep Space Nine, Voyager, etc.), most Federation starships take years just to travel within the quadrants of the Milky Way galaxy. The Enterprise reaches the galaxy’s center in a matter of minutes.

Questions: Why is the Enterprise always the nearest starship to these galactic troubles? There’s never another ship in the quadrant to help out, which leads me to believe that whoever oversees coverage at Starfleet isn’t doing their job. Moreover, the original crew’s Enterprise never seems ready for space travel; it’s always running in a state of disrepair with only a skeleton crew, giving Scotty a mild heart attack in the process. Also, why are the planetary systems always given curious names like Nimbus, Daled, and so forth? Spanning countless languages across the galaxy, there must be enough proper and improper nouns to mix up the naming conventions a little, even if we have to start naming planets after random objects like Kitten or Snowshoe. And how does the Enterprise get to the center of the galaxy so fast? Based on reports from other shows (The Next Generation, Deep Space Nine, Voyager, etc.), most Federation starships take years just to travel within the quadrants of the Milky Way galaxy. The Enterprise reaches the galaxy’s center in a matter of minutes.

Sure enough, after five minutes of warp-speed travel, the Enterprise reaches The Great Barrier to their own astonishment, forcing us to ponder why, if it was so easy, no one had tried this before? Anyway, once there, they find an entity on a rocky planet called Sha Ka Ree (not the home planet of Chaka Khan), posing as various gods throughout the universe. Sybok believes it to be the Vulcan god of emotions; McCoy believes it’s the Christian god. But when the being demands a ride out of The Great Barrier on the Enterprise, Kirk rightfully questions why God would need a starship. This angers God, who zaps Kirk with electro-eye rays. So Kirk beams onto an approaching Klingon ship and blasts God into oblivion. End of story. And yet, the message remains unclear. Did The Final Frontier just suggest God is real, but an alien has been posing throughout various worlds in our galaxy? Or did it suggest there is no God, just an alien with eye-blasting powers? Either way, God or the alien entity posing as God is killed. That Shatner and his film find this distinction unimportant is troublesome.

Just as wearisome are the special effects, which were produced in an FX house out of New York, instead of the Los Angeles-based wizards at Industrial Light & Magic who completed the FX on earlier Star Trek features. With a limited budget of $33 million and a tight production schedule to ensure no lost momentum after the previous picture, The Final Frontier feels rushed on almost every technical level. From the subpar animations on the god-alien to the underwhelming model work on the spaceships, the production looks shoddy, save for the few scenes filmed on-location in Yosemite National Park and the Mojave Desert. Although no one can accuse Paramount executives of knowing far in advance that Shatner’s efforts would bring the franchise close to ruin, the studio remains guilty of not giving Shatner the means to make a better picture. Only Jerry Goldsmith’s score stands out as a truly exceptional quality of the film. Nevertheless, the film went on to gross $63 million in worldwide receipts, a far cry from the projected $200 million Paramount analysts had hoped for.

Undoubtedly, the film’s strong opening gave way to poor reviews and fan disappointment, to which the untidy script and unrelentingly corny dialogue can be attributed. Regardless of the high stakes (they’re trekking to find God, after all), a large portion of the film involves fluff—camping, comic relief, an alien stripper cat, etc. The conflict feels unengaging, the risks almost nonexistent. Sure, the Klingons pose a minor concern, but what Klingon has ever gotten the jump on James Tiberius Kirk? And then there’s the religious nut who takes hostages to prove his faith. Shatner said he wanted Sybok to encompass a cultist or televangelist, healing through the power of his quack-like skill, driven by his own conviction. But with Sybok at the center of the film’s conflict, the screenplay incorporates its intended theological underpinnings only at the most superficial level.

Undoubtedly, the film’s strong opening gave way to poor reviews and fan disappointment, to which the untidy script and unrelentingly corny dialogue can be attributed. Regardless of the high stakes (they’re trekking to find God, after all), a large portion of the film involves fluff—camping, comic relief, an alien stripper cat, etc. The conflict feels unengaging, the risks almost nonexistent. Sure, the Klingons pose a minor concern, but what Klingon has ever gotten the jump on James Tiberius Kirk? And then there’s the religious nut who takes hostages to prove his faith. Shatner said he wanted Sybok to encompass a cultist or televangelist, healing through the power of his quack-like skill, driven by his own conviction. But with Sybok at the center of the film’s conflict, the screenplay incorporates its intended theological underpinnings only at the most superficial level.

The Final Frontier was the second-lowest box-office earner for the franchise to date, making a trifle more than 2002’s disappointing Nemesis. Shatner’s film began as a project to stroke his own ego and ended as a studio obligation, wherein Paramount was more concerned about a release date than a quality product. Certainly the worst film to come from the Star Trek-verse, The Final Frontier was even panned by series creator Gene Roddenberry. At least upon the film’s release in 1989, Trekkies could fall back on episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation. Today, when revisiting the Star Trek film in sequence, only the promise of the final film boasting the original crew, Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country, lightens the empty feeling left by Shatner’s misdirected little disaster.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review