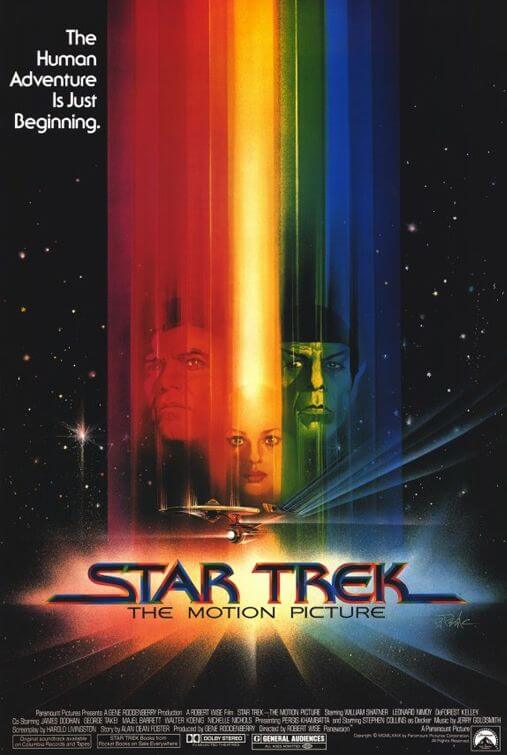

Star Trek: The Motion Picture

By Brian Eggert |

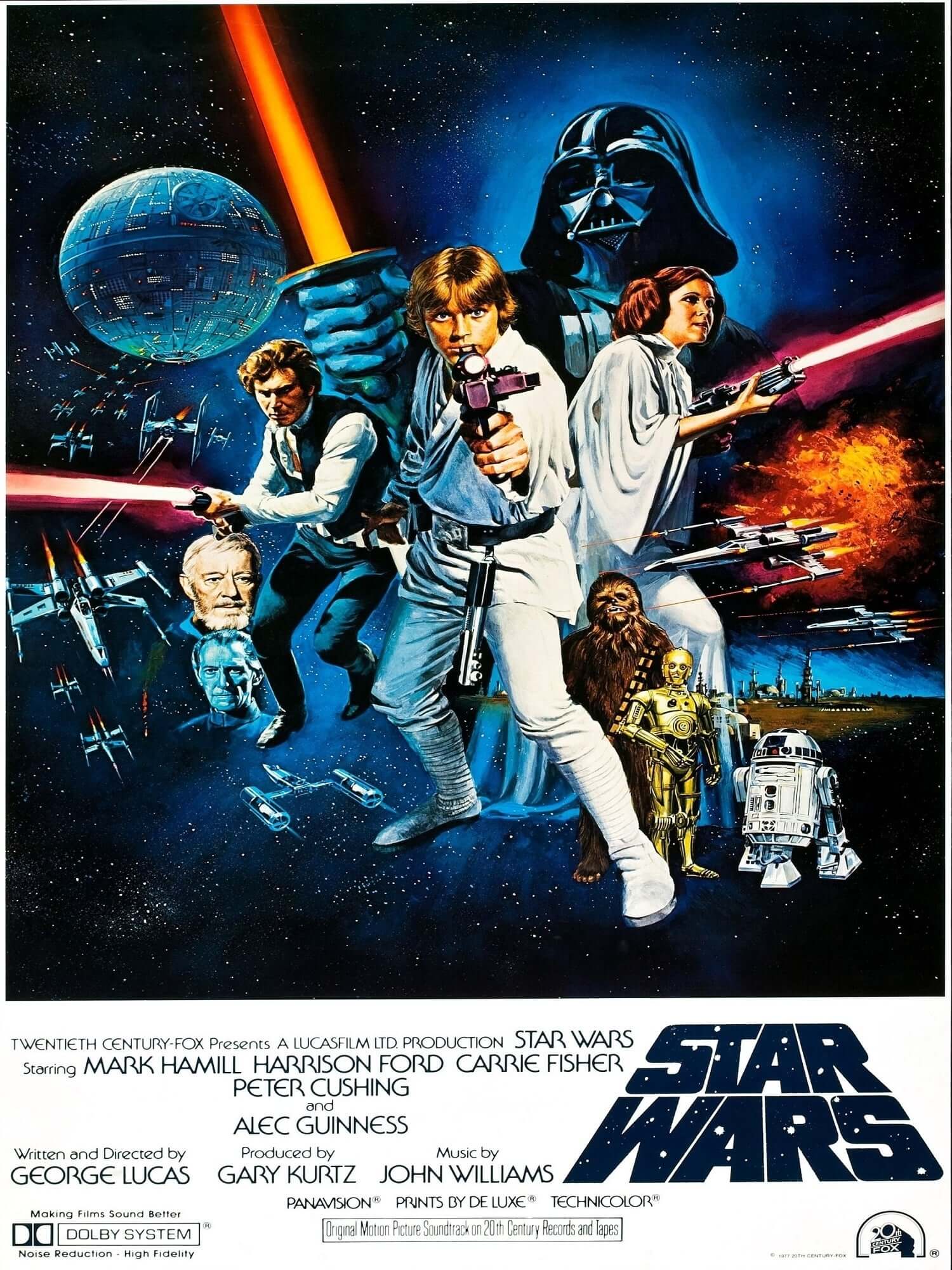

Star Trek had a short-lived three-year run on NBC television from 1966 to 1969. The ratings never impressed, and eventually, the series faded away. It wasn’t until the franchise’s second film, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982), that Star Trek hit any kind of commercial stride. Indeed, science fiction was then an unproven genre, with only the (considerable) example of Star Wars (1977) to justify any financial risk on Hollywood’s part. However, Star Trek has always had a loyal fanbase. After the show’s cancelation, fans wrote letters to both the show’s creator, Gene Roddenberry, and, strangely enough, the White House, demanding a Star Trek film. As would often be the case with all things Star Trek, fans kept the franchise alive; they religiously watched the show’s syndicated network reruns, which led to the series finally earning a profit, therein making way for 1979’s Star Trek: The Motion Picture. And if the first film remains oddly detached from what came before and after it, its stellar box-office performance meant there were more sequels in the future.

Roddenberry first explored options for a feature film version in 1968, but his plans fell apart after delivering several unsatisfactory scripts to Paramount Pictures. Instead, in the 1970s, Roddenberry used the lingering popularity and produced a fleeting animated series, and then sparked initial plans for another live-action show called Star Trek: Phase II. Sets were being built, and an initial episode, entitled “In Thy Image,” was written for Phase II. Meanwhile, Roddenberry was still petitioning Paramount to make a film version of his TV show. Paramount was wary and noncommittal at first because, aside from Star Wars, sci-fi had been reserved for B-movies. Only after the impressive box-office performance of Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), a decidedly less commercial effort than Star Wars, would Paramount acknowledge that a market existed for a Star Trek film.

In fact, Paramount had become so desperate to make their own Star Wars that they canceled production on Star Trek: Phase II and used many of the would-be show’s sets and costumes for the upcoming film. The studio intended a budget of $15 million for their feature film and announced Robert Wise, director of the legendary sci-fi picture The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), had signed to helm the Enterprise into cinematic space. Staples of science fiction ranging from Ray Bradbury to Harlan Ellison had earlier proposed story concepts, but several credited and uncredited contributors eventually adapted “In Thy Image” into a feature-length screenplay. Elsewhere, the studio entered into tough negotiations with the show’s actors, particularly William Shatner and Leonard Nimoy, to return. Along with studio execs, Shatner and Nimoy had considerable input for the script.

In fact, Paramount had become so desperate to make their own Star Wars that they canceled production on Star Trek: Phase II and used many of the would-be show’s sets and costumes for the upcoming film. The studio intended a budget of $15 million for their feature film and announced Robert Wise, director of the legendary sci-fi picture The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), had signed to helm the Enterprise into cinematic space. Staples of science fiction ranging from Ray Bradbury to Harlan Ellison had earlier proposed story concepts, but several credited and uncredited contributors eventually adapted “In Thy Image” into a feature-length screenplay. Elsewhere, the studio entered into tough negotiations with the show’s actors, particularly William Shatner and Leonard Nimoy, to return. Along with studio execs, Shatner and Nimoy had considerable input for the script.

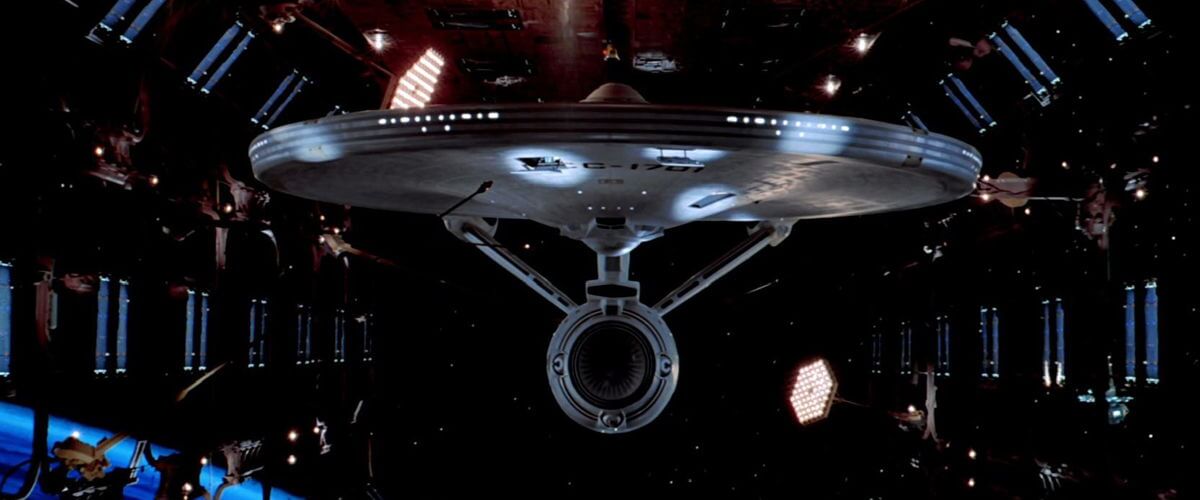

Wise and the studio ordered all of the Phase II sets and costumes rebuilt, expanded, and in some cases completely redesigned. (It may have been easier, perhaps even cheaper, for the production to work from scratch.) The publicity department made sure it was known the filmmakers consulted NASA and authors like Isaac Asimov for technical advice. Richard H. Kline served as cinematographer and, working closely with Wise and the film’s several special FX wizards (including the later addition of Douglas Trumbull, of Close Encounters of the Third Kind renown), the production fell increasingly more behind. Special FX, in-camera or otherwise, had to be considered for nearly every shot, which had not been considered by Wise or Kline, setting the production behind by weeks and ratcheting the budget up to a whopping $46 million. For example, the sequence where the Enterprise leaves the spaceport in the opening required nearly fifty shots, each taking an entire day to set up the lighting, models, and FX equipment.

When the film was eventually released, it earned $139 million in box-office receipts, thus beginning the longest-running film series in Hollywood history, next to James Bond. But still, the film feels far removed from the show or subsequent films—reliant entirely on special effects and reaction shots to them. The dialogue is sparse, foregoing character introductions for those unfamiliar with the television series. Indeed, even those devoted to the show might not recognize the thin descriptions of the beloved characters, whose dynamic was the key feature of the show. The characters don’t live and breathe; rather, Wise attempts to outperform his actors and the story with spectacle. And while spectacle may have worked for Wise in the past (The Sound of Music comes to mind), here the material feels as though it’s been done a disservice. Granted, Star Trek: The Motion Picture arrives with an interesting scenario and clever twist in the finale, but the entire film feels like an extended medium-grade episode of the show, and it’s mishandled in the director’s and studio’s attempt to differentiate the material in film from television.

The story begins with an energy cloud of some unknown origin approaching Earth, destroying ships and space stations in its path. A newly constructed Enterprise remains docked and under assembly, while its new captain, Willard Decker (Stephen Collins), prepares her to intercept the cloud on Starfleet’s order. Seeing this as an opportunity to seize the captain’s chair once more, the newly promoted Admiral Kirk (William Shatner) arrives onboard, reduces Decker to the rank of commander, and becomes captain again. Kirk is reunited with his former crew: Dr. McCoy (DeForest Kelley), engineer Scotty (James Doohan), helmsman Sulu (George Takei), communications officer Uhura (Nichelle Nichols), and tactical officer Chekov (Walter Koenig). Even science officer Spock (Leonard Nimoy) is picked up along the way.

The story begins with an energy cloud of some unknown origin approaching Earth, destroying ships and space stations in its path. A newly constructed Enterprise remains docked and under assembly, while its new captain, Willard Decker (Stephen Collins), prepares her to intercept the cloud on Starfleet’s order. Seeing this as an opportunity to seize the captain’s chair once more, the newly promoted Admiral Kirk (William Shatner) arrives onboard, reduces Decker to the rank of commander, and becomes captain again. Kirk is reunited with his former crew: Dr. McCoy (DeForest Kelley), engineer Scotty (James Doohan), helmsman Sulu (George Takei), communications officer Uhura (Nichelle Nichols), and tactical officer Chekov (Walter Koenig). Even science officer Spock (Leonard Nimoy) is picked up along the way.

When they engage the cloud, the formation takes one of the crew, Lt. Ilia (Persis Khambatta), and replaces her with a mechanized android to observe human behavior. The crew is subject to its every whim, as it examines them from a purely logical point of view; this is particularly torturous for Decker, who loved Ilia. The drone claims it works for V’ger, the central hub of a massive craft inside the space cloud. When the Enterprise reaches that hub, they discover V’ger is really the lost NASA satellite Voyager, sent back to Earth by an alien race who built the massive construct surrounding the satellite, believing it would help the Voyager complete its mission. Since its mission was to absorb knowledge, it allows Ilia and Decker to merge into one being comprised of logic and humanity, and so a new form of life is born.

If all of this sounds rather dull, you’re right, it is. You’ll notice there’s no description of encounters with dastardly Klingons or shifty Romulans, no phaser-laden space battles, and no away missions in which the crew encounters bizarre alien monsters. The film arrived in 1979, which is part of the problem. Hollywood had recently proven the science fiction genre valid with not only the massive space-Western Star Wars but also the heady wonder of Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Trying to elevate the material by emulating these proven successes, the filmmakers seem to forget everything that made the show enjoyable. The crew barely banters in their signature way, so those debates of brash instinct (Kirk) meets logic (Spock) meets humanism (McCoy) are entirely absent. What dialogue we do hear hardly has the charm, wit, or sarcasm found in the later films.

Most frustrating are the eye-popping special effects, rendered by way of incredibly detailed miniatures of Starfleet crafts and enormous alien bases. They look wonderful, of course; Trumbull is a master. Cinematically, they represent prolonged visual masturbation, carrying on in slow shots designed for visual spectacle alone. They’re shot with a brooding camera in very, very long takes. Sci-fi fans will find comparisons to 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) unavoidable. Wise lingers too long on technology, but without the wonder that Stanley Kubrick might imbue, and later he attempts an almost psychedelic view inside V’ger’s cloud, except with none of the substance of Kubrick’s landmark film. Wise’s direction presents an embarrassingly derivative low point in his career, as being unfamiliar with the series prior to filming, he could do nothing more but copy from other filmmakers.

Most frustrating are the eye-popping special effects, rendered by way of incredibly detailed miniatures of Starfleet crafts and enormous alien bases. They look wonderful, of course; Trumbull is a master. Cinematically, they represent prolonged visual masturbation, carrying on in slow shots designed for visual spectacle alone. They’re shot with a brooding camera in very, very long takes. Sci-fi fans will find comparisons to 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) unavoidable. Wise lingers too long on technology, but without the wonder that Stanley Kubrick might imbue, and later he attempts an almost psychedelic view inside V’ger’s cloud, except with none of the substance of Kubrick’s landmark film. Wise’s direction presents an embarrassingly derivative low point in his career, as being unfamiliar with the series prior to filming, he could do nothing more but copy from other filmmakers.

With fans jealously supporting Roddenberry’s lovable universe, Star Trek: The Motion Picture might have failed and ended the brief phenomenon that was the show’s cult popularity. Instead, the series’ supporters flocked to theaters to carry the film into box-office triumph and justify Paramount’s decision to make Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan—what many consider to be the real beginning of the cinematic Star Trek adventures. Revisiting the film today, something isn’t right; it feels as though the cast and crew were copied and replaced with lifeless robots. Only the most devoted apologists embrace this first entry, which lacks almost every joyous attribute carried by the television show, regardless of its technical merits. Everyone else was left scratching their heads until the next entry in the franchise, which offered universal entertainment value and a stronger connection to the show.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review