Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home

By Brian Eggert |

Imagine a Star Trek film that considers elaborate space battles, photon torpedoes, phaser blasts, and despotic villains inconsequential to the narrative, and so it resolves not to include them. Now imagine that visual effects do not drive the film; in fact, the majority of its story doesn’t even take place in space, but instead on Earth. What’s more, imagine that Earth is not the utopian vision of the future dreamed up by Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry—it’s the unremarkable Earth of 1986. Still more unlikely, imagine that the film’s narrative had been structured around animal activism, specifically marine conservation, in support of saving humpback whales, ultimately hoping to “save this planet from its own short-sightedness.” In the face of these improbable qualities, imagine something else: that the film becomes a blockbuster and reaches more people than an activist work ever could—creating a platform for its activist message, but doing so without sacrificing the integrity of iconic Star Trek characters or raw entertainment value.

A franchise blockbuster like the one described above would never be made in today’s Hollywood, that much is certain. The pitch even sounds absurd, writing it out like that. And yet, Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home manages to be everything described above, and more. Indeed, the fourth entry in Star Trek’s cinematic franchise contains an ambitious and improbable setup; one can imagine that present-day Paramount Pictures would laugh at “save the whales”-centric franchise film. While deviating from the standard blockbuster formula, The Voyage Home tries something new within the confines of Roddenberry’s universe; and its attempt at something so bold is also the major difference between Star Trek and other franchises. As Star Wars concerns itself almost exclusively with selling toys and expanding its plot, the Star Trek series remains open to reflective philosophical pursuits. Even more impressive, The Voyage Home diverges from your customary Star Trek picture, which so often features the Enterprise crew facing off against a singular enemy.

To be sure, the villain-less conflict of The Voyage Home explores its characters and learns to appreciate them in new ways. It accomplishes this without violence, yet retains the characters’ charm over the audience. Developed by producer Harve Bennett and director Leonard Nimoy, the concept behind the film is a noble and rare one for a blockbuster. Using a sci-fi setup involving the impending destruction of Earth, the film takes a stance to protect the dwindling population of humpback whales, address their status as an endangered species, and further emphasize the importance of ongoing efforts to protect them. More than any other film in the Star Trek franchise, the outcome is lighthearted, as close to pure comedy as the series would ever come. And despite this departure from the typical procession of alien encounters and science-fiction thrills, the film thrives on imagination and the very nature of these beloved characters. In that sense, it’s the truest of Star Trek features with the original cast.

To be sure, the villain-less conflict of The Voyage Home explores its characters and learns to appreciate them in new ways. It accomplishes this without violence, yet retains the characters’ charm over the audience. Developed by producer Harve Bennett and director Leonard Nimoy, the concept behind the film is a noble and rare one for a blockbuster. Using a sci-fi setup involving the impending destruction of Earth, the film takes a stance to protect the dwindling population of humpback whales, address their status as an endangered species, and further emphasize the importance of ongoing efforts to protect them. More than any other film in the Star Trek franchise, the outcome is lighthearted, as close to pure comedy as the series would ever come. And despite this departure from the typical procession of alien encounters and science-fiction thrills, the film thrives on imagination and the very nature of these beloved characters. In that sense, it’s the truest of Star Trek features with the original cast.

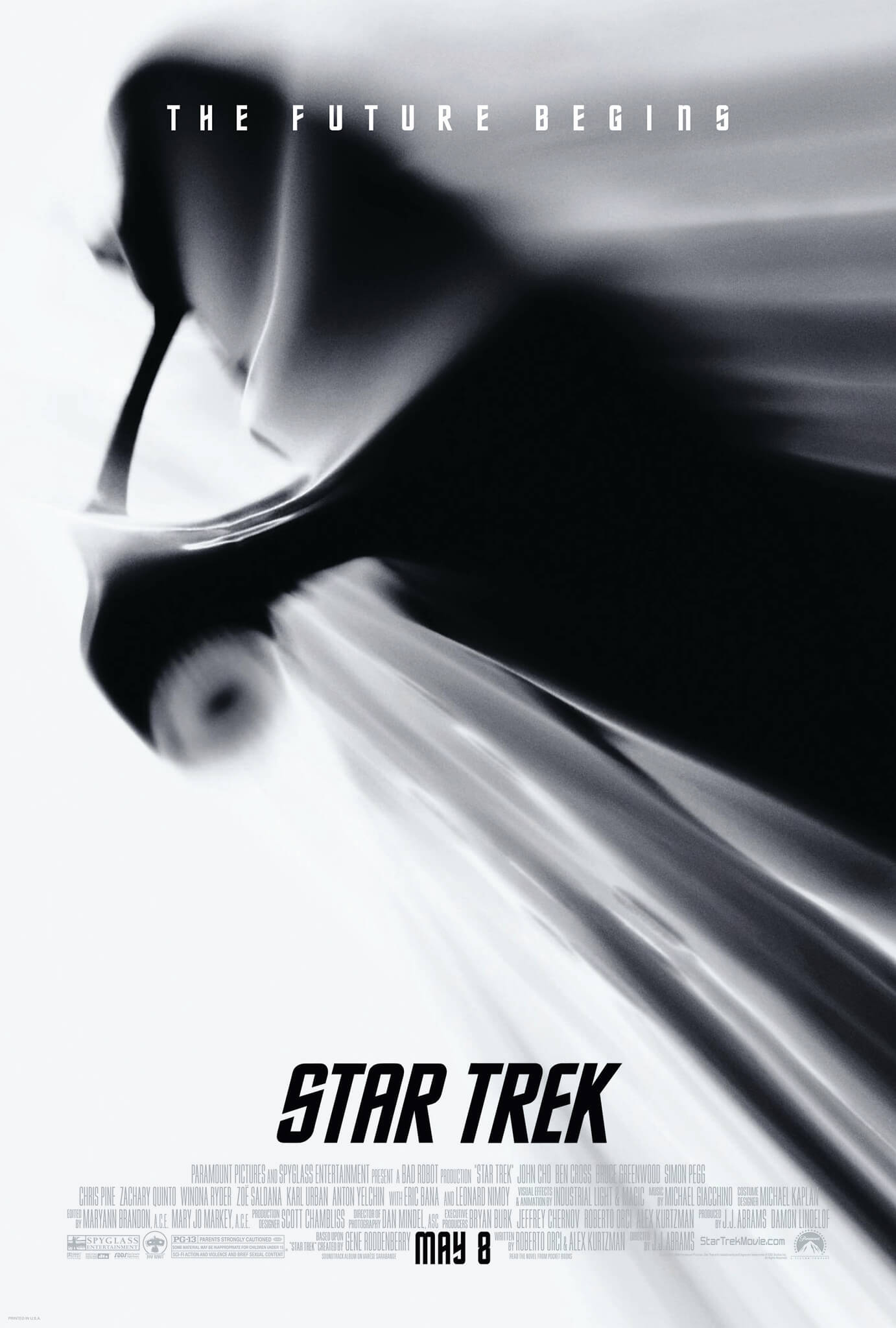

Discussions about a fourth Star Trek film began as Paramount Pictures was pleased with director Nimoy’s progress on The Search for Spock. They asked him to return as director of the next picture, giving him artistic license to explore whatever he envisioned. At this, William Shatner balked about returning for another film, during which time Nimoy, Bennett, and writer Ralph Winter conceived an idea about the young Kirk and Spock at Starfleet Academy (the root idea would eventually inspire J.J. Abrams’ 2009 reboot Star Trek). In the meantime, two things were certain about Nimoy’s proposed film: 1) Nimoy and Bennett wanted a more cheerful story next to the operatic titles that preceded it, and 2) they wanted a time-travel scenario contemporary audiences could relate to. They considered ideas such as a plague curable only by a pharmaceutical found in deforested rainforests, or a critique of the oil industry—but both issues were deemed too weighty for their first requirement. Finally, Nimoy and Bennett settled on supporting the Save the Whales campaign, which started about a decade earlier.

As was often the case with Star Trek films to this point, The Voyage Home’s script passed through several writers and iterations. Although Beverly Hills Cop writer Daniel Petrie, Jr. was initially hired to pen the script and launched discussions with that film’s star, Eddie Murphy, to appear, Murphy passed on the part written for him. Paramount wasn’t satisfied with Petrie’s script anyway. The studio wanted Nicholas Meyer back to write again since he delivered the script for The Wrath of Khan in just 12 days. Bennett and Meyer collaborated on a new draft, and Meyer incorporated many elements from his own excellent time-travel film, Time After Time (1979), about author H. G. Wells using his time machine to travel back to San Francisco to stop Jack the Ripper. Unlike any other Star Trek film, the shooting took place mostly on location in San Francisco, as opposed to soundstages built to look like alien planets or the Enterprise corridors. Along with the witty screenplay, the open-air shoot seemed to invigorate the actors.

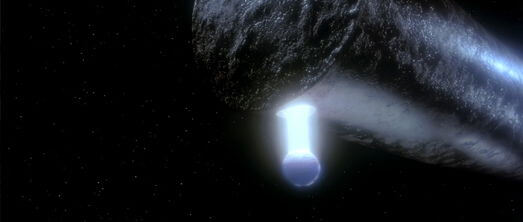

Of course, there’s hardly a need for star trekking in this entry, as the Enterprise was destroyed in the last film, The Search for Spock. The story begins almost immediately after its predecessor, with Captain Kirk (Shatner) and the crew of the Enterprise still on the Vulcan home planet, awaiting the newly reborn Spock (Nimoy) to become once again whole. With the Enterprise destroyed, her crew plans to return home and has refitted a Klingon Bird of Prey to read HMS Bounty. At the same time, a mysterious probe—a black cylinder as singular as the monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)—approaches Earth, disrupting the power of any nearby vessel with its indecipherable signals, causing the planet’s weather patterns to go haywire, thus threatening to end all life. Tracking the object, Spock determines its signal matches that of a humpback whale, utterly extinct in the twenty-third century. And in one of those best-left-unexplained cinematic time-travel moments, the crew resolves to journey to an earlier period in time, recover a humpback whale, and return to the future to answer the alien probe’s hail. Without much precursory debate, they slingshot around the Sun and use its gravity to fly into the past, circa 1986.

Their cloaked Klingon ship lands in a quiet park in San Francisco, and immediately the film shifts gear into a fish-out-of-water comedy, as men from the future acclimate themselves to 1980s culture. Sure enough, revisiting the film today offers an added level of humor by looking back at the 1980s in its prime (the shoulder pads, the Cold War hysteria, the electronic pop music). Moreover, Nimoy and his cast seem unbound by the typical constraints of a Star Trek picture; they’re willing to have fun with these characters and poke fun at themselves (a cabbie calls Kirk a “dumbass”). But isn’t that the point—that the characters are displaced from their normal environment and forced to adjust, hence the intended culture-clash humor? Certainly, Nimoy wasn’t concerned with preserving the usual Star Trek recipe when Spock administers his “Vulcan nerve punch” to a loud punk-rocker on a city bus (played by an associate producer on the film), an act that earns applause from his fellow passengers. Donning a white headband to cover his pointy ears and eyebrows, Spock also engages in some hilarious moments of comic timing, courtesy of Spock’s dry, straight-man routine juxtaposed against Kirk’s more animated presence. And let’s not forget McCoy’s (DeForest Kelley) assessment of the twentieth century’s “Medieval medicine” after he walks through a 1986 hospital.

Getting back to the main plot, the crew has three missions: Scotty (James Doohan), Sulu (George Takei), and McCoy conceive plans for a whale-holding tank within the Klingon ship, meeting some resistance when they visit an industrial factory and speak of yet-uninvented technologies. Uhura (Nichelle Nichols) and Chekov (Walter Koenig) head for a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, aptly named the USS Enterprise, for an alternate power source to recrystallize the Klingon ship’s dilithium crystals. But the Cold War era’s paranoid naval authorities don’t appreciate Chekov or his Russian accent near their nuclear reactor. Lastly, Kirk and Spock must convince Dr. Gillian Taylor (Catherine Hicks) at the local Cetacean Institute (played by the Monterey Bay Aquarium) to give them two humpback whales. Gillian laments releasing the two whales into the wild, where they’ll likely be hunted and killed. Some awkward moments ensue as Kirk tries to convince Gillian that he can protect the sea mammals on his spaceship, and understandably, she reacts to his claims of being from the future with skepticism.

Only because of her desperate fear that they’ll otherwise be slain does Gillian agree to Kirk’s proposal. After a series of daring rescues—first saving Chekov from his U.S. government captors, second transporting the whales onto the Klingon ship before whalers attack—Kirk and crew return to the future. There, the whales’ song kindly asks the unidentified object to stop sending Earth’s weather into a frenzy. Overall, the story proves universal and straightforward enough to be accessible to non-Trek fans, speaking about environmental responsibility, and in effect forcing the audience to consider the implications of their present-day actions or inactions concerning the future of whales. Though near extinction when this film was made in 1986, around the height of the Save the Whales campaign, humpback whales have since made a comeback, increasing in numbers by several thousand in the North Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. But they remain on the endangered species list to continue their conservation, as whaling ships still hunt them illegally in international waters. Unfortunately, there’s not always a cloaked and water-logged Klingon Bird of Prey to fly to the rescue, which makes the film’s message still relevant today.

Only because of her desperate fear that they’ll otherwise be slain does Gillian agree to Kirk’s proposal. After a series of daring rescues—first saving Chekov from his U.S. government captors, second transporting the whales onto the Klingon ship before whalers attack—Kirk and crew return to the future. There, the whales’ song kindly asks the unidentified object to stop sending Earth’s weather into a frenzy. Overall, the story proves universal and straightforward enough to be accessible to non-Trek fans, speaking about environmental responsibility, and in effect forcing the audience to consider the implications of their present-day actions or inactions concerning the future of whales. Though near extinction when this film was made in 1986, around the height of the Save the Whales campaign, humpback whales have since made a comeback, increasing in numbers by several thousand in the North Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. But they remain on the endangered species list to continue their conservation, as whaling ships still hunt them illegally in international waters. Unfortunately, there’s not always a cloaked and water-logged Klingon Bird of Prey to fly to the rescue, which makes the film’s message still relevant today.

Not only does the film support the specific Save the Whales campaign, it considers animal rights and equality. At one point, Gillian defends her deep love of her whales: “My compassion for someone is not limited to my estimation of their intelligence.” Meaning, animals are no less empathetic than humans just because they are animals. After all, humans, too, are animals. The Voyage Home returns to a familiar theme established in The Wrath of Khan and The Search for Spock in support of this idea. Ever since Spock (half emotional human, half logical Vulcan) died in The Wrath of Khan and was reborn in The Search for Spock, he’s been trying to put himself together again. But he cannot reconcile human behavior. “Humans make illogical decisions,” he remarks. His observation refers to both the dramatically-satisfying-but-ultimately-illogical choice that saved Spock (“The needs of the one outweigh the needs of the few.”) or the choice to allow the eradication of whales. This idea is compounded by raw footage of actual whale killings shown at the Cetacean Institute, which begs the question: Where is the logic behind allowing such senseless slaughter to take place? There is no logic behind it—only apathy.

The Voyage Home became the first Star Trek feature screened in Moscow thanks to its whale-friendly message. The screening was arranged by the World Wildlife Fund to celebrate their recent ban on whaling and took place well before the Cold War had ended. Additionally, the film’s criticism of thoughtless disregard for life appealed to the Soviets in attendance. Reportedly, they applauded over McCoy’s line, “The bureaucratic mentality is the only constant in the universe,” suggesting the Soviets wanted peace. The Soviet response to this film was extraordinary since Klingons were conceived in part as a metaphor for the Soviets, leaving Russia’s Trekkie population few in numbers. But The Voyage Home hopes for equality between animals and humans alike. It attempts to put distance between the traditional, and somewhat outdated, conflict between the Federation and the Klingon Empire as an allegory for the U.S. against the Soviet Union. Earning more than $133 million worldwide on a $21 million budget, the film dethroned that year’s major hit, another fish-out-of-water tale, Crocodile Dundee, from its top spot on the U.S. box office, and lured a much larger audience than just Trekkies.

Detractors from The Voyage Home’s almost universal acclaim argued the film felt disconnected from a typical Star Trek yarn. This remains baffling since episodes in the original television series often featured the Enterprise crew time-traveling to a specific era—in that regard, the film was very much adhering to an established Star Trek formula. Others argued the humpback whales were merely the film’s McGuffin; however, had the film preached further about marine conservation, it may have ceased to be entertainment. No narrative film should communicate a political or social commentary first, and its story second. The message to protect whales exists as part of the plot and part of the subtext in terms of education on biodiversity. Stressing the point further would have upset the delicate, pitch-perfect balance between entertainment and commentary Nimoy achieves. Furthermore, the whales offer the emotional kernel for understanding Gillian, and an endearing cause for the Enterprise crew beyond the standard spaceship battles and zapping bad guys with futuristic weaponry.

Detractors from The Voyage Home’s almost universal acclaim argued the film felt disconnected from a typical Star Trek yarn. This remains baffling since episodes in the original television series often featured the Enterprise crew time-traveling to a specific era—in that regard, the film was very much adhering to an established Star Trek formula. Others argued the humpback whales were merely the film’s McGuffin; however, had the film preached further about marine conservation, it may have ceased to be entertainment. No narrative film should communicate a political or social commentary first, and its story second. The message to protect whales exists as part of the plot and part of the subtext in terms of education on biodiversity. Stressing the point further would have upset the delicate, pitch-perfect balance between entertainment and commentary Nimoy achieves. Furthermore, the whales offer the emotional kernel for understanding Gillian, and an endearing cause for the Enterprise crew beyond the standard spaceship battles and zapping bad guys with futuristic weaponry.

Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home may be the most important film within the franchise, as it demonstrates how the potential of its venerable characters transcends space and time. Remove the technology, the fascinating yet questionable science, and the perceptible surface of the Star Trek continuum, and what’s left are the universality of the plot and involving characters who engage their audience through their ensemble dynamic. Though the jokes are cheeky and understandably dated, there’s also a timeless quality to the story thanks to the time-travel device. For this reason, The Voyage Home is the least dated of any Star Trek picture. It’s exceptional that Nimoy chose not to limit himself as a filmmaker by once again voyaging to the farthest reaches of the galaxy. It’s even more exceptional that his gamble worked. In a commercial series whose most successful entries rely on an entrenched formula, this film’s success, despite its uncharacteristic approach, should serve as an example to other such franchises unwilling to divert from the norm.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review