Star Trek: Insurrection

By Brian Eggert |

Most criticisms of Star Trek: Insurrection object that it too closely resembles just another good episode of the television show, suggesting this quality somehow makes it inferior to the franchise’s other films. Wasn’t the excellence of Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987-1994) precisely what inspired this series of Star Trek films in the first place? Isn’t the success of that show greatly responsible for reinvigorating interest in Gene Roddenberry’s campy 1960s invention through a modern approach? So, if the film would make one helluva episode, but boasts Hollywood-quality special effects and presentation, why do fans reject the product as a feature? After all, Insurrection contains several hilarious moments between this beloved cast, as well as disturbing real-world parallels that bring added weight to the material. Whereas other Star Trek features feel less connected to the series’ legacy for their cinematic ambitions, Insurrection feels more Star Trek than any other Star Trek film, in the best way possible.

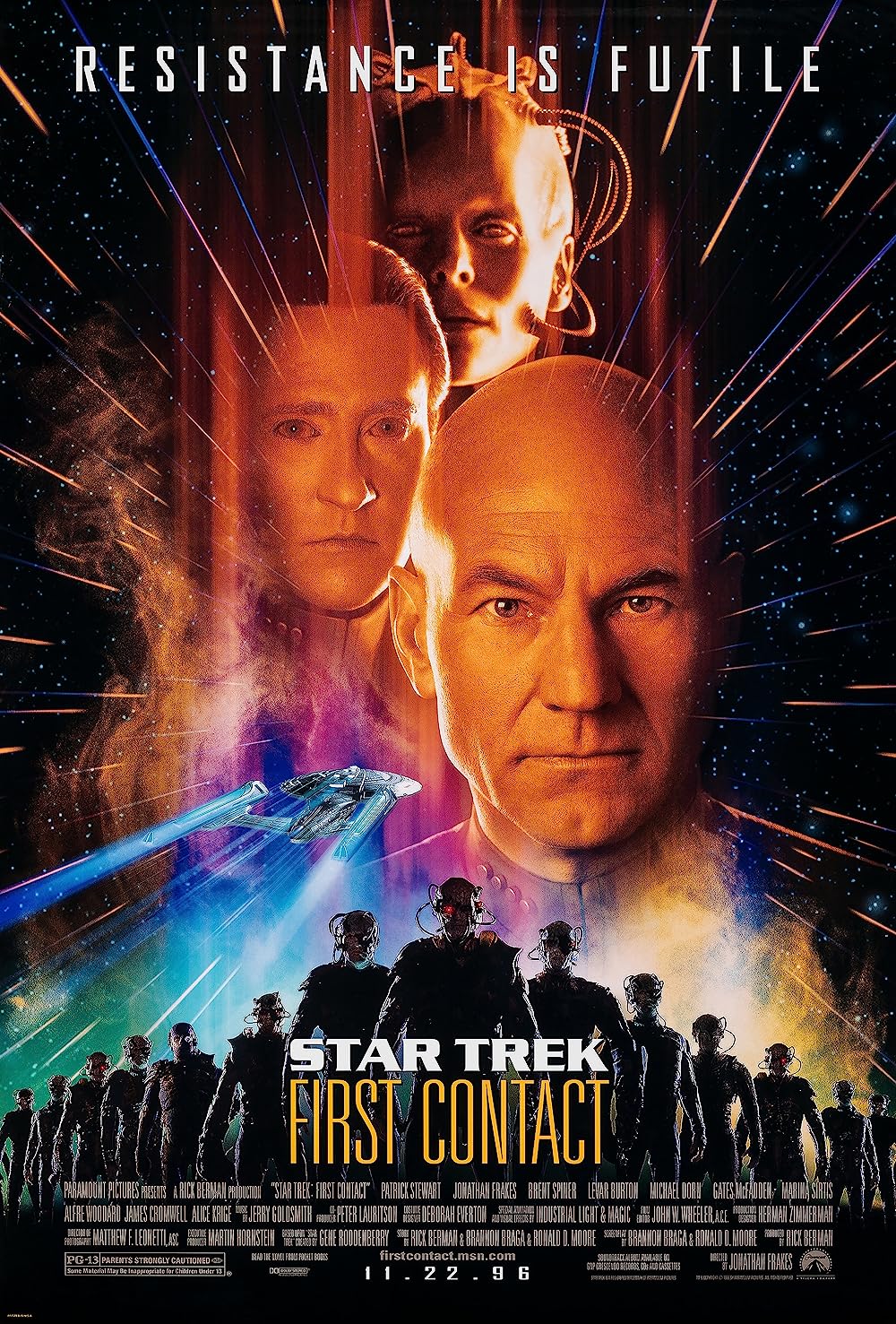

Critics such as David Luty of Film Journal International called it “another extended episode” and argued it should have taken on a broader, pointedly cinematic scope. However, most of The Next Generation’s extended episodes already boasted a cinematic scope. Two-parters like “Chain of Command,” “Time’s Arrow,” and “The Best of Both Worlds” often involved elaborate spy missions, time travel, or monumental space battles. And so, we must wonder, how much one-upmanship can an audience expect before a series becomes too bloated? Expectations for Insurrection were understandably high after First Contact, enough so that no matter what Paramount released for their third film starring The Next Generation cast, fans would ultimately compare the outcome to its predecessor and be disappointed. Others attribute their disappointment with Insurrection to the absurd notion that even-numbered Star Trek films are always better than the odd-numbered, a superstition with several exceptions.

After First Contact, Paramount Pictures wanted a lighter Star Trek film likened to The Voyage Home, a major performer for the studio. Star Trek: Deep Space Nine writer and co-creator Michael Piller was asked to write the script, and he teamed with producer Rick Berman. Together they explored several ideas, many of them detailed in Piller’s making-of book, called Fade In: From Idea to Final Draft, The Writing of “Star Trek: Insurrection,” published in 2005 after his death. The screen story would eventually share much in common with The Next Generation episode “Homeward,” in which the Enterprise is forced to break the Prime Directive to relocate a pre-industrial alien species from their dying planet, but without them knowing. However, Piller’s genius stroke was making the film’s alien species a technologically advanced society that chooses to live an agrarian, tech-free lifestyle, thus making the relocation legal, but morally wrong. Since cast member Jonathan Frakes broke cinematic ground with First Contact, his first feature film, the studio invited him back for Insurrection and gave him a budget of $58 million, even more than his previous effort. Frakes’ cinematographer Matthew F. Leonetti also returned behind the camera.

After First Contact, Paramount Pictures wanted a lighter Star Trek film likened to The Voyage Home, a major performer for the studio. Star Trek: Deep Space Nine writer and co-creator Michael Piller was asked to write the script, and he teamed with producer Rick Berman. Together they explored several ideas, many of them detailed in Piller’s making-of book, called Fade In: From Idea to Final Draft, The Writing of “Star Trek: Insurrection,” published in 2005 after his death. The screen story would eventually share much in common with The Next Generation episode “Homeward,” in which the Enterprise is forced to break the Prime Directive to relocate a pre-industrial alien species from their dying planet, but without them knowing. However, Piller’s genius stroke was making the film’s alien species a technologically advanced society that chooses to live an agrarian, tech-free lifestyle, thus making the relocation legal, but morally wrong. Since cast member Jonathan Frakes broke cinematic ground with First Contact, his first feature film, the studio invited him back for Insurrection and gave him a budget of $58 million, even more than his previous effort. Frakes’ cinematographer Matthew F. Leonetti also returned behind the camera.

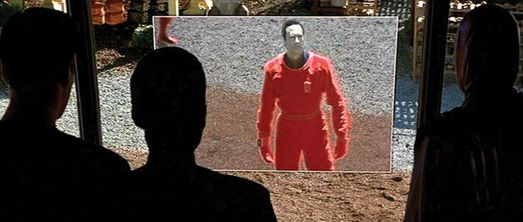

The story opens when android crewmember Data (Brent Spiner) malfunctions while observing the quiet, seemingly pre-industrial Ba’ku people on their home planet. The survey team led by the Federation and Son’a, an alien species that maintain their dying bodies through skin grafts and excessive plastic surgery, hide all around the Ba’Ku, searching for scientific answers to the planet’s natural wonder: a de-aging and healing property. Their world is surrounded by rings that make everyone on the planet subject to constant “metaphasic radiation,” which slows their aging, allowing them eternal youth and mastery of their chosen crafts. In essence, they’re living in a Fountain of Youth. Their surveillance party is exposed when Data, somehow damaged, goes haywire, breaking the Federation’s Prime Directive of non-interference or making their presence known to underdeveloped worlds.

Far away on the Enterprise, the usual starship hustle and bustle busies the crew, until Admiral Dougherty (Anthony Zerbe) orders Captain Picard (Patrick Stewart) and company to recover their android, and then negotiate the release of Federation scientists held prisoner by the Ba’Ku. When the Enterprise arrives inside a nebula-encased system dubbed the Briar Patch, they find the Ba’Ku to be farmers and artisans, yet fully capable and knowledgeable of advanced technologies. They’ve simply decided to live in harmony with Nature. Village leader Anij (Donna Murphy) tells Picard, “Where can warp drive take us, except away from here?” The “hostages” are not prisoners at all, but rather welcomed guests. Soon it becomes apparent that both the Federation and Son’a have plans for the Briar Patch—especially after Admiral Dougherty and his seedy Son’a cohort Adhar Ru’afo (F. Murray Abraham) prompt Picard to leave. They want to create a medical colony and use the healing radiation to cure various maladies throughout the galaxy. Regardless, Picard decides to stay, believing there’s a plot to relocate the Ba’Ku forcibly.

Meanwhile, the Enterprise begins to experience the healing radiation’s effect, and they can appreciate why the Federation wants the planet: Picard feels young again and explores a romance with Anij—whose years have left her with an ability to slow time and live in the moment. Cmdr. Riker (Frakes) and Counselor Troi (Marina Sirtis) chase after each other like horny teenagers; Number One even shaves his long-present beard during a couple’s bubble bath. The blind engineer LaForge (Levar Burton) gets his sight back. And moody Lt. Cmdr. Worf (Michael Dorn) goes through Klingon puberty. These character-based asides come and go with a blithe airiness that reminds us why we love The Next Generation. At the same time, the Enterprise crew realizes Admiral Dougherty and Ru’afo will resort to violence to clear out the Ba’Ku, leaving Picard no choice but to rebel against his commanding officer. So he rushes the locals into nearby caves to hide them from the Federation and the Son’a, while Riker takes over the Enterprise for some clever starship dogfights against Son’a forces.

In his review, Roger Ebert suggested the Federation and Son’a should prevail in this situation: “Wouldn’t it be right to sacrifice the lifestyles of 600 Ba’ku in order to save billions?” He argued that, when he questioned the film’s cast and crew at the 1998 premiere, even they could see both sides of the argument, how the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. But we’re dealing with Gene Roddenberry’s world here, which is comparatively idealistic compared to our own—a future without currency or food shortages, with considerable medical advancements, and enough planets in the galaxy to avoid overpopulation. Furthermore, the film suggests the Son’a are an aggressive race that once lived on the Ba’Ku planet long ago, but they were forced out because of their violent tendencies, and want to move the Ba’Ku primarily out of revenge. To counter Mr. Ebert’s argument, isn’t it the Son’a’s own damn fault for leaving? Should any weaker race automatically submit to a stronger one? Does a stronger power have the right to wipe out a weaker country or an entire planet’s population just because they need something? In many ways, the actions of the Federation and Son’a reflect U.S. foreign policy to a disturbing degree. Ebert seems to defend it. But as Picard questions, “How many people does it take before it becomes wrong?”

These are themes and questions frequently explored in The Next Generation, a show that delved into the logical loopholes in idealism as an ongoing focus. Perhaps this is why Insurrection’s associations with the show remain so constant among critics and fans because its narrative seems to augment the show’s formula and give its recurrent themes cinematic life. Consider Leonetti’s camerawork, how he shoots with a temperance required by the story rather than blatantly cinematic movements. Consider how the picture spends the majority of its running time on a single planet, whereas other films jump about the galaxy on their “Star Trek”. Consider how the story feels like—as Insurrection’s detractors are quick to note—“just another mission,” whereas the other Star Trek films employ a scope reaching beyond that of the show. This is not so much a criticism of the film, but an acknowledgment of how it resolves to tell its story without needing to artificially proclaim itself as cinema to meet commercial demands.

While recognizing that these similarities to the show’s structure exist, it must also be stated how entertaining and well-crafted this film proves to be. Earning a small profit from its $70 million box-office take, Insurrection may be the most undervalued of all Star Trek films, for what seems an unjust criticism that the film’s story feels like an episode of the show. Scenes such as when Picard sings Data down from his malfunctioned state by reciting a segment of Gilbert and Sullivan’s H.M.S. Pinafore, or Data’s simplistic conversations about how children play with the Ba’Ku boy, capture the essence of their respective characters. And yet, here’s a story that challenges viewers with a question of morals and logic, resolving that in an ideal world, specifically the one Roddenberry created, the circumstances do not warrant the genocide of one group to save another.

Ultimately, Star Trek: Insurrection underscores an injustice common in our imperfect world, and questions why our civilization continues to let such things happen. Has history taught us nothing? If the film’s critics consider these un-cinematic themes, and more appropriate for a two-part episode, so be it. But any one of TNG’s many two-part episodes, if aired on the big screen, would make a fine motion picture (in recent years, several theater chains have hosted two-part episodes of The Next Generation for theatrical exhibitions). These criticisms ultimately point out how well the show proved to achieve a cinematic scope and blur the lines between the two mediums. Star Trek films will always seem episodic in nature; after all, the trekking continues despite the events in any single film, with ongoing sequels comparable to next week’s episode. What remains significant is how well Insurrection’s story is told, how it touches on all these beloved characters, and how it tackles the series’ archetypal themes.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review