Star Trek III: The Search for Spock

By Brian Eggert |

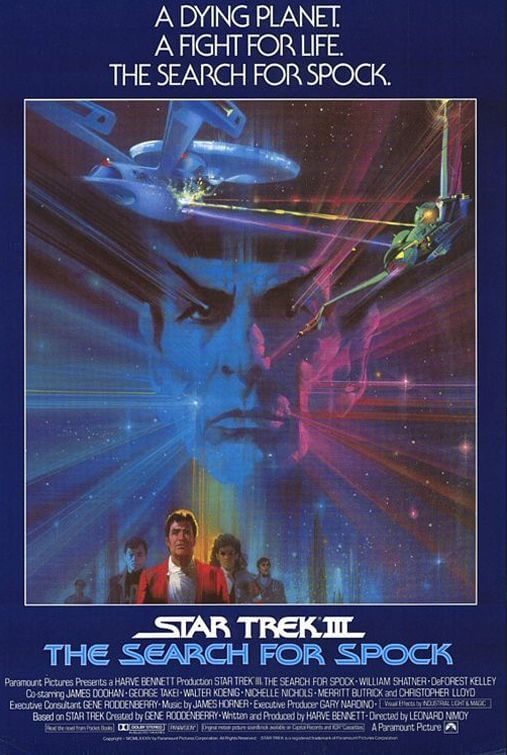

Some Trekkies adhere to the bogus theory that only the even-numbered Star Trek films are good, whereas the odd-numbered are not. Upon closer examination, this truism falls apart. Granted, everyone’s favorites The Wrath of Khan and First Contact are even, whereas everyone’s least favorites The Motion Picture and The Final Frontier are odd. It’s not that the odd-numbered films are poor, though indeed one or two are; but rather, for some reason, they usually contain less actionized plots, and thus are less likely to serve up a blustering crowd-pleaser. Consider Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, which follows the transmigration of an Enterprise crewmember’s soul, or katra in the original Vulcan. A spiritual journey is hardly typical material for a massive blockbuster, which is probably why writer-producer Harve Bennett included some Klingon hijinks for good measure.

And yet, the story is what Time critic Richard Schickel called, “the first space opera to deserve that term in its grandest sense.” Indeed, Paramount Pictures didn’t release another swashbuckler like the film’s immediate predecessor, but a weighty, sometimes cornball drama filled with themes of rebirth. After sour reactions to Spock’s death at the end of The Wrath of Khan, Bennett began writing the script backward, starting with the final sequence of Spock’s rebirth and working his way back, since reviving Spock was the sole requirement Paramount had for this sequel. Produced for $16 million, the studio kept the production costs (and thus the production value) low. The loyal fanbase ensured The Search for Spock would gross $76 million, providing another profitable release and solidifying the franchise’s future, regardless of lukewarm responses.

Picking up where The Wrath of Khan left off, the film begins with Spock (Leonard Nimoy) dead, having sacrificed himself to save the Enterprise and her crew, his body jettisoned onto a planet being terraformed by the Genesis Device. This doohickey creates life where there is none, sprouting unchecked vegetation and atmosphere in abundance. With Spock’s body on the planet, he begins to regenerate. Meanwhile, the Enterprise has docked at an Earth spaceport, the crew still grieving over the loss of their comrade. Admiral Kirk (William Shatner) has noticed that Dr. McCoy (DeForest Kelley) is acting a little strange. When Spock’s father, Sarek (Mark Lenard), arrives and learns of McCoy’s behavior, he claims that Spock probably transferred his katra into McCoy just before he died. Sarek tasks Kirk with recovering Spock’s body and returning to the Vulcan home planet, where he will arrange an ancient ceremony to return Spock’s katra.

Picking up where The Wrath of Khan left off, the film begins with Spock (Leonard Nimoy) dead, having sacrificed himself to save the Enterprise and her crew, his body jettisoned onto a planet being terraformed by the Genesis Device. This doohickey creates life where there is none, sprouting unchecked vegetation and atmosphere in abundance. With Spock’s body on the planet, he begins to regenerate. Meanwhile, the Enterprise has docked at an Earth spaceport, the crew still grieving over the loss of their comrade. Admiral Kirk (William Shatner) has noticed that Dr. McCoy (DeForest Kelley) is acting a little strange. When Spock’s father, Sarek (Mark Lenard), arrives and learns of McCoy’s behavior, he claims that Spock probably transferred his katra into McCoy just before he died. Sarek tasks Kirk with recovering Spock’s body and returning to the Vulcan home planet, where he will arrange an ancient ceremony to return Spock’s katra.

Easier said than done. Back on the Genesis Planet, dastardly Klingon Captain Kruge (Christopher Lloyd) wants to get his hands on the life-bringing Genesis Device and reformat it into a weapon. On the surface below, Vulcan scientist Lt. Saavik (Robin Curtis) and Kirk’s son David (Merritt Butrick), both characters introduced in The Wrath of Khan, find a young Vulcan boy aging at an alarming rate, slowly growing into everyone’s favorite pointy-eared science officer. Luckily, Kirk disobeys orders and sneaks away with the Enterprise, joined only by the bridge crew, to stop the Klingons, recover the Genesis Device, and reinstate Spock’s katra from McCoy’s body to its newly reborn and rightful host on the Vulcan home planet.

Some awkward casting is evident when Robin Curtis demonstrates that she’s not Kirstie Alley, who played Saavik in The Wrath of Khan and does not appear again here. Alley purportedly wanted too much money to reprise her first screen role from the previous film. Rather than merely write out the character, Paramount replaced the actress, a choice that leaves the film feeling inconsistent. Curtis’ presence is unnatural and rigid, too much so even for a logic-obsessed Vulcan. Furthermore, as much as the Kruge character is needed to supply some space action, his motivation is oversimplified, although Lloyd does wonders with the one-dimensional role.

Though Spock is mainly absent from the film in Nimoy form, his floating head appears on the poster, and his name on the director’s chair. Leonard Nimoy jumped at directing duties for The Search for Spock after his positive experience on The Wrath of Khan, a film he initially said would be his last space voyage. More than any other Star Trek film director, Nimoy renders all the characters with humanistic traits, which challenges the raw entertainment value of any photon torpedo battle. He captures how the actors and characters alike play off one another in a fixed rhythm—particularly Shatner’s Kirk and Kelley’s McCoy in this film—thus solidifying their permanent status in film and pop-culture history as genre icons. Doing this with sensitivity and consideration for the dramatic depth of the story is what makes Nimoy’s direction exceptional.

And yet, there are creative choices that feel unnatural to a motion picture and better suited for a two-part episode. Before the opening credits, for example, audiences are subject to a recap of what happened in the previous film (as though “Previously on Star Trek” should have opened the film). Such a generic intro hardly helps distinguish the film series from its television roots, but the visual splendor (save for some cheap-looking soundstage sets) and impressive effects make up for that. The aforementioned rigid acting and seemingly forced Klingon conflict also present unnecessary comparisons to the show. Though, undoubtedly the studio pushed for a villain, as saving Spock would hardly be enough to draw non-fan audiences—since of course that would happen in this sequel. (After The Wrath of Khan, and even before its release, fans wrote angry letters to Paramount protesting Spock’s death.)

Flaws aside, The Search for Spock is pleasant, character-driven entertainment. And so, once again, we must question the system used to rank the Star Trek films by their numeric sequence, even-numbered being good, odd-numbered being bad. Since The Search for Spock is the third film in the series, many wave off its dramatic merits solely in support of this superstition, ignoring how the film elevates this franchise from a mere adventure in the stars to a full-fledged theatrical experience, complete with a narrative that has us emotionally invested in familiar and lovable characters and their fates. In assessing the film, audiences discover what kind of Star Trek viewer they are: Either they’re the kind who allows themselves to become emotionally involved in the story, or they’re the casual viewer watching just to see spaceships explode and the occasional alien vaporized by a phaser blast. Consider this critic in the former category.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review