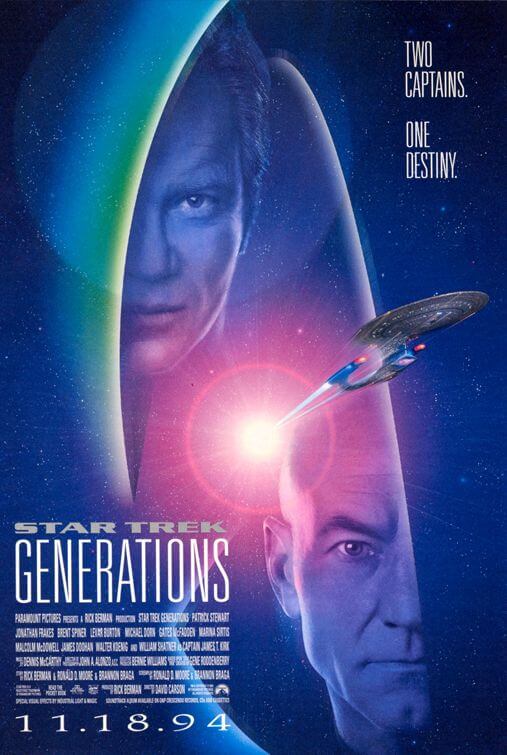

Star Trek: Generations

By Brian Eggert |

Star Trek: Generations serves as another bridge between the established original crew and the innovative, much-loved chemistry of The Next Generation cast. Although thematically speaking, the torch had already been passed to future generations of the Federation’s Starfleet in 1991’s Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country, the notion of a crossover film containing both Captain Kirk and Captain Picard, and their two crews, intrigued Paramount Pictures—if only from a promotional perspective. After all, such a film would transcend generational gaps in viewership, so those who grew up watching the televised Star Trek series (1966-1969) and subsequent films, and those who discovered the series with The Next Generation crew (1987-1994), could be brought together in a single motion picture. Generations sought to please both traditionalist and contemporary fans, and the shows’ respective legacies, even while the overall franchise was growing swiftly out of control with two additional shows (Deep Space Nine, Voyager, and later Enterprise). Instead, the result was perhaps not what devoted fans hoped for, but in its own right, it’s a solid production and entertaining Star Trek adventure.

Paramount approached producer Rick Berman in 1992, just under a year after The Undiscovered Country was released, to develop ideas for a feature film starring The Next Generation’s Captain Jean-Luc Picard and company. The Next Generation’s head writers and story consultants, Ronald D. Moore and Brannon Braga, teamed with Berman and others to conceive the story, while Moore and Braga penned the screenplay in May of 1993. As usual with Star Trek films, the story depended much on how much William Shatner and Leonard Nimoy were willing to participate. Nimoy declined an offer to direct and costar, citing problems with the script, and a particular blandness in his proposed dialogue that Paramount refused to correct. Nimoy claimed lines written for him could be spoken by anyone—and, as it turns out, he was right. When he turned down the offer, the same dialogue was given to James Doohan with no changes. Shatner agreed to make an extended appearance, and so Moore and Braga wrote around that. All of The Next Generation would star in the film, of course, whereas the original series’ Enterprise crew made intermittent appearances. Deforest Kelley, who appeared on the first episode of The Next Generation, couldn’t get approval from the studio’s on-set health insurance goons to appear, so his lines were given to Walter Koenig. Nichelle Nichols and George Takei did not appear.

After Nimoy and filmmaker Nicholas Meyer (The Wrath of Khan and The Undiscovered Country), both refused to return to the director’s chair, Paramount settled on David Carson, whose experience was limited to television—in particular, some early episodes of Deep Space Nine and the excellent episodes of The Next Generation entitled “Yesterday’s Enterprise” and “The Next Phase”. Proceeding under Paramount and the producers’ watchful eyes, Carson had a $35 million budget and limited resources, in part because Generations proved to be a test. If The Next Generation crew’s film could make a profit, then more films would follow. But this meant Paramount forced Carson to shoot on the cheap. When a Klingon Bird of Prey detonates in space, the footage was the same explosion from The Undiscovered Country. For the big finale’s destruction of the Enterprise, they simply used television-grade ship models and sets from the TV series, even though they were designed specifically for lower-resolution TV screens and therefore lacked detail. No matter, since their demolition allowed future films with The Next Generation crew to harbor more elaborate ships, sometimes constructed completely with computer-generated effects as technologies improved.

After Nimoy and filmmaker Nicholas Meyer (The Wrath of Khan and The Undiscovered Country), both refused to return to the director’s chair, Paramount settled on David Carson, whose experience was limited to television—in particular, some early episodes of Deep Space Nine and the excellent episodes of The Next Generation entitled “Yesterday’s Enterprise” and “The Next Phase”. Proceeding under Paramount and the producers’ watchful eyes, Carson had a $35 million budget and limited resources, in part because Generations proved to be a test. If The Next Generation crew’s film could make a profit, then more films would follow. But this meant Paramount forced Carson to shoot on the cheap. When a Klingon Bird of Prey detonates in space, the footage was the same explosion from The Undiscovered Country. For the big finale’s destruction of the Enterprise, they simply used television-grade ship models and sets from the TV series, even though they were designed specifically for lower-resolution TV screens and therefore lacked detail. No matter, since their demolition allowed future films with The Next Generation crew to harbor more elaborate ships, sometimes constructed completely with computer-generated effects as technologies improved.

Nevertheless, there were plenty of impressive visuals in the film, such as the wavy energy ribbon that both propels the plot and serves as a MacGuffin. Meanwhile, Carson insisted on hiring cinematographer John A. Alonzo (Harold and Maude, Chinatown), and the moodier, shadow-heavy, pointedly cinematic lighting helped disguise many of the production’s cheaper-looking elements—which remain visible only to those looking with a microscopic eye. Getting the word out about the upcoming film spawned the first website dedicated to promoting a movie’s release, now a staple for any film’s advertising budget and the foundation of viral marketing. Star Trek Generations was eventually released on November 18, 1994, about six months after the award-winning final episode “All Good Things…” aired, and the film opened to lukewarm reviews and a relatively strong box-office performance (about $118 million worldwide). Many detractors compared the film to a two-part episode of The Next Generation, which is less of a slight on the film than it sounds. Given the narrative and sometimes cinematic quality of two-part episodes on the show, a negative connotation hardly seems apt.

Indeed, The Next Generation outclassed previous and subsequent Star Treks shows by balancing human drama and science-fiction, and Generations does much the same. The film begins when, in the twilight of his career, James T. Kirk seemingly dies saving the rookie crew of the new Enterprise from an “energy ribbon”. In fact, the ribbon—called the Nexus—has snatched him up and carried him away, and he remains inside until the next generation of Starfleet, namely the crew of the Enterprise-D, finds him in the twenty-fourth century. During Kirk’s rescue, he pulled a madman named Saron (Malcolm McDowell) from the Nexus, inside of which Saron had found his deceased wife and child, somehow preserved alive and well. The Nexus, you see, makes your most desired dreams come true—the Enterprise-D’s venerable bartender, the infinitely wise Guinan (Whoopi Goldberg), also rescued from the Nexus by Kirk, describes it as “being wrapped inside joy, as if joy were something tangible.” Saron is obsessed with getting back inside. He plans to destroy an entire solar system to alter the Nexus’ course over a planet, where he intends to stand and hitch a ride back to joy.

On the Enterprise-D, human drama preoccupies the crew. Lt. Worf (Michael Dorn) earns a promotion to Lt. Commander. Capt. Picard (Patrick Stewart) mourns the accidental deaths of his brother and nephew (characters established on the excellent episode “Family”). Android crewmate Data (Brent Spiner) activates his “emotions chip” and attempts to control a wellspring of newly experienced feelings. Meanwhile, the crew launches an investigation at a Federation space station that was attacked, revealing some dastardly Klingons—namely, the show’s popular villainesses, the Duras sisters (Barbara March and Gwynyth Walsh)—may be responsible. As it turns out, the Durases have teamed with Saron. However, there doesn’t appear to be a way to stop Saron’s plan, at least not from the outside. And so, Picard enters the Nexus and sets out with Kirk to stop Saron’s plan, ending when the elder captain falls to his death after saving the day. Meanwhile, Commander Riker (Jonathan Frakes) leads a mission to stop the Duras sisters, which ends with the Enterprise crash-landing on a nearby planet.

Fans responded to Kirk’s demise with anger, believing the circumstances unsuitable for the hero who had survived so many perilous away missions and fought his way out of numerous spaceship battles. During debates about which one makes the best Enterprise captain, Kirk or Picard, Kirk’s brash, singular personality often wins over the emotionally complex puzzle of Picard. Audiences like their heroes straightforward and their death scenes grandiose, I suppose, and so Kirk falling to his death from a metal bridge didn’t feel right. McDowell even received death threats from one Trekkie so distraught over the scene. Then again, Kirk was originally phasered to death by Saron, but test audiences balked at the notion, claiming Kirk deserved better (imagine what Trekkies would’ve done to McDowell if Kirk died by Saron’s hands). Paramount ordered reshoots, but Kirk’s fall proves more “real” than the storybook finale Trekkies were hoping for. And yet, had he died nobly on the Enterprise bridge, followed by a momentous funeral where everyone could say goodbye, that would be too easy—reality hardly ever lets anyone say goodbye, and that’s a persistent theme in Generations, linking Saron’s desire to return to his family in the Nexus (fantasy) to Picard accepting that his family name will not live on (reality).

The Next Generation series was always about bringing a sense of the possible to the Star Trek universe, particularly in terms of its science-fiction, whereas the original series seemed rooted in the impossible and ideal. Astrophysicists such as Stephen Hawking have attested to The Next Generation’s technological and scientific accuracy, or how the show builds stories around astronomical hypotheses, such as wormholes or time bubbles—concepts ripe for exploration in a weekly television series. The Kirk crew seems to chase after the adventurous and romantic aspects of space, whereas Picard’s crew delves into the real (or at least theoretically real). Even from a dramatic perspective, The Next Generation layers its characters beyond the often-predictable roles founded by Kirk, Spock, and McCoy. Consider Data, who at first, with his dependence on computerized logic and lack of emotion, was deemed merely a stand-in for Spock. As the series evolved, so did the character, imbuing him with a desire to become human, and even subtle underlying feelings. Finally, in this film, Data’s “emotions chip” (although used by the writers mostly as a comic relief tool), serves as an impossible-yet-malfunctioning fantasy for Data—to the point where he disengages it in the film’s last scenes. To his android reality, artificial emotions are not real.

Buried in the subtext of Star Trek: Generations resides the theme that fantasy does not substitute a harsh-but-true dose of reality and therefore establishes the entire Picard crew as favorable against the fantastical Kirk crew—at least among viewers with a penchant for hard science. The film’s main plot and subplots each contain a Reality vs. Fantasy theme: Saron’s violent drive to return to the Nexus, an acknowledged illusion, twists him into something evil; Data’s emotions chip, ostensibly a step away from his unemotional Self by artificial means (ignoring, of course, that he’s an android), proves problematic; Picard and Kirk both resist the ribbon’s fantasy, however appealing, for the grim realities of their lives—though Kirk undoubtedly still looks at stopping Saron as a wild buckaroo adventure, and perhaps that’s why he dies—because he doesn’t respect the reality of the situation. Regardless, fans and critics alike noted that too much was destroyed (the Enterprise-D and Kirk himself) within Generations to make the torch passing an effortless process. Other complaints that too few of the original cast members returned, precisely the conspicuous absence of Leonard Nimoy, left longtime fans disappointed.

Buried in the subtext of Star Trek: Generations resides the theme that fantasy does not substitute a harsh-but-true dose of reality and therefore establishes the entire Picard crew as favorable against the fantastical Kirk crew—at least among viewers with a penchant for hard science. The film’s main plot and subplots each contain a Reality vs. Fantasy theme: Saron’s violent drive to return to the Nexus, an acknowledged illusion, twists him into something evil; Data’s emotions chip, ostensibly a step away from his unemotional Self by artificial means (ignoring, of course, that he’s an android), proves problematic; Picard and Kirk both resist the ribbon’s fantasy, however appealing, for the grim realities of their lives—though Kirk undoubtedly still looks at stopping Saron as a wild buckaroo adventure, and perhaps that’s why he dies—because he doesn’t respect the reality of the situation. Regardless, fans and critics alike noted that too much was destroyed (the Enterprise-D and Kirk himself) within Generations to make the torch passing an effortless process. Other complaints that too few of the original cast members returned, precisely the conspicuous absence of Leonard Nimoy, left longtime fans disappointed.

Whereas fan service might be in order for this type of event, the filmmakers simply told a story with some worthwhile themes for these beloved characters, and as a result, the film received poor notices for the filmmakers’ unwillingness, or more accurately their inability, to live up to more grandiose fan expectations. For many, the powerful storytelling didn’t matter because the film could not accommodate everyone’s wishes for the final appearance of James T. Kirk, regardless of whether his death was symbolically in favor of The Next Generation or not. Alas, my own reading and appreciation of the film remain a minority opinion. Ultimately, the degree to which you enjoy Generations is a question of why you’re watching any Star Trek film or television series in the first place. Are you watching for no other reason than pure space adventure escapism in all its formulaic glory? Or do the characters, their lives, and their often three-dimensional personalities draw you, while the science-fiction elements only sweeten the pot? This seems to be the very difference between the original Star Trek series and The Next Generation, and why the latter camp should enjoy this film.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review