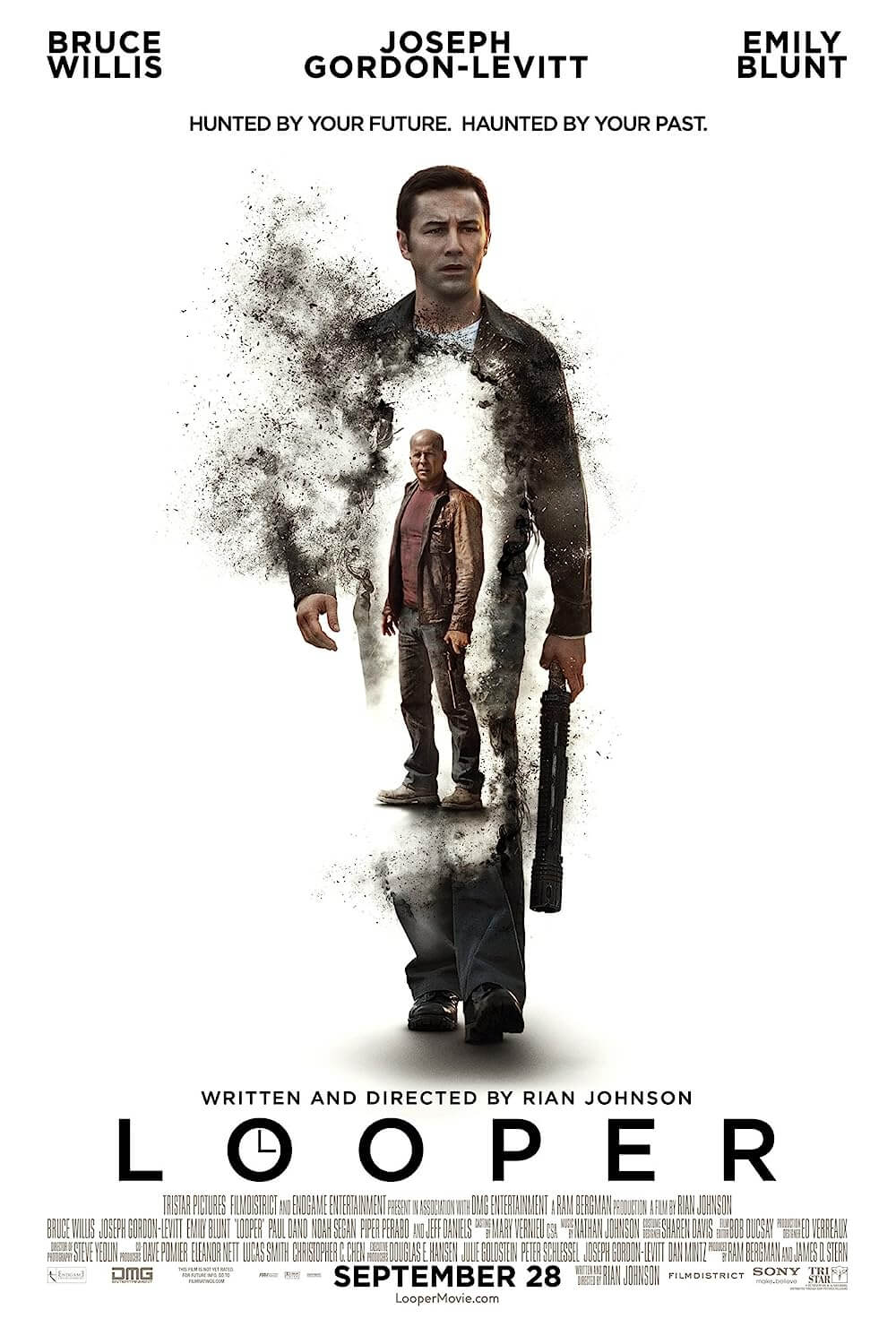

Star Trek: First Contact

By Brian Eggert |

Star Trek: First Contact is not merely a great Star Trek film. This is a great film, period. A triumph of concise writing and formal bravado, the Jonathan Frakes-directed feature tells a story that requires no prior knowledge of Gene Roddenberry’s original vision, nor any entrenched familiarity with the cast of Star Trek: The Next Generation television series (1987-1994). Rarely would such a picture draw audiences outside of its niche market, but here the approach sees beyond the series’ limitations and becomes appropriately universal, resolving to be simply terrific and engaging entertainment. Often the best films throughout history contain a widespread appeal and have no demographic whatsoever, making them timeless. Much like Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, viewers of First Contact need not be Trekkies to appreciate what an exciting, sometimes scary, often funny, and formally imposing film this 1996 release proved to be. Filled with impressive special FX and incredible acting from star Patrick Stewart (and his fellow cast members), First Contact remains at the top of many lists of the best Star Trek films ever produced. And likewise, it belongs among the best entries in the science-fiction genre.

After the minor success of Star Trek: Generations, Paramount Pictures finally retired the original Enterprise crew and devoted their full attention to the first autonomous feature starring The Next Generation cast. Longtime producer Rick Berman insisted on a time travel aspect to the new film, whereas writers Brannon Braga and Ronald D. Moore wanted to include the show’s popular villain The Borg. They settled on both. The running story was called Star Trek: Renaissance and would feature the Enterprise crew traveling back in time to the fifteenth century, specifically in Europe, where they would fight the Borg in centuries-old castles, and where Data (Brent Spiner) would become the apprentice of Leonardo da Vinci—a concept unavoidably kitschy. Fortunately, Braga and Moore reconsidered the concept alongside Berman and resolved to send the Enterprise back in time to a date still forthcoming. In other words, both timelines occur in the future: the standard twenty-fourth-century timeline of The Next Generation cast, as well as their past in the twenty-first century, in which famed Star Trek character Zephram Cochrane first tests warp drive and, as a result, makes contact with humanity’s first alien race: the Vulcans.

Given the production’s allotted budget of $45 million and high expectations—especially after it was announced that the fan-favorite villains, the Borg, were set to appear—the production made its riskiest decision by hiring an inexperienced director. Filmmakers such as Ridley Scott (Alien) and John McTiernan (Predator) turned down Paramount’s offers, but when cast member Jonathan Frakes, who played Cmdr. William Riker was asked to direct, he leaped at the opportunity. However, Frakes didn’t set out to make another Star Trek film, as David Carson had done on Star Trek Generations. In fact, Frakes had never made a feature film; his directorial experience at that point had been only a handful of The Next Generation and Deep Space Nine episodes—some of the best, in fact (“The Drumhead,” “Cause and Effect,” and “The Chase”). But unlike those who passed on the project, Frakes knew the material and its sometimes confining margins. To prepare, he studied genre milestones like Close Encounters of the Third Kind and 2001: A Space Odyssey; he also rewatched his favorites from Steven Spielberg, James Cameron, and the aforementioned Scott—filmmakers who know how to apply science-fiction to a picture that rises above demographics.

Given the production’s allotted budget of $45 million and high expectations—especially after it was announced that the fan-favorite villains, the Borg, were set to appear—the production made its riskiest decision by hiring an inexperienced director. Filmmakers such as Ridley Scott (Alien) and John McTiernan (Predator) turned down Paramount’s offers, but when cast member Jonathan Frakes, who played Cmdr. William Riker was asked to direct, he leaped at the opportunity. However, Frakes didn’t set out to make another Star Trek film, as David Carson had done on Star Trek Generations. In fact, Frakes had never made a feature film; his directorial experience at that point had been only a handful of The Next Generation and Deep Space Nine episodes—some of the best, in fact (“The Drumhead,” “Cause and Effect,” and “The Chase”). But unlike those who passed on the project, Frakes knew the material and its sometimes confining margins. To prepare, he studied genre milestones like Close Encounters of the Third Kind and 2001: A Space Odyssey; he also rewatched his favorites from Steven Spielberg, James Cameron, and the aforementioned Scott—filmmakers who know how to apply science-fiction to a picture that rises above demographics.

Star Trek films carry a television stigma that prevents some general audiences (non-Star Trek fans) from seeing any film in the franchise as genuine cinema. Where Frakes’ direction differs are his technical and creative choices. Take his cinematographer, Matthew F. Leonetti (Dead Again, Strange Days), who employs innovative angles and lenses that push the boundaries of the Star Trek aesthetic. But he does so without removing his audience from the established visual language of the series (Leonetti observed filming on the sets of Deep Space Nine and Voyager to prepare). The majority of the franchise’s previous pictures use straightforward, unspectacular camerawork and editing, giving proper allowances to the characters and their adapted-from-TV world. The few exceptions stand out as some of the most inspired Star Trek films, namely Nicholas Meyers’ The Wrath of Khan and The Undiscovered Country. Frakes achieves a joyous balance between form and function, even while demonstrating almost expressionistic moments through Leonetti’s fluid camerawork. From a directorial perspective, Frakes outgrows his television roots superbly, and yet his film never feels unfamiliar or too expressive to the show’s devotees.

Of course, knowing the film’s background as explored on the television series, and the characters’ prior involvement in the events as they unfold, will only add to the viewer’s enjoyment, though it is by no means required. Bridging the Season 3 finale and Season 4 premiere, the Emmy Award-winning two-part episode “The Best of Both Worlds” earned praise from critics and fans alike for its cinematic scope. The plot involved Captain Jean-Luc Picard (Patrick Stewart) being kidnapped and converted into the leader of a biomechanical race called the Borg, a relentless cybernetic hive mind determined to “assimilate” all other species into its collective. Though he’s saved by his crew and returned to humanity again, Picard was haunted throughout the remaining seasons by lingering traces of the enemy, stirring in him a sometimes unreasonable drive to destroy The Borg, even though they became increasingly human-like. In the Season 5 episode “I, Borg,” Picard’s crew finds a lone Borg drone and gradually awakens its humanity; they name him Hugh and send him back to the collective, hoping to infect the hive mind with individuality. Later in “Descent,” the two-parter connecting Season 6 and Season 7, the crew learns that Hugh’s humanity has infected the Borg and left them driven by negative emotions. In the Borg continuity, this is where First Contact picks up.

Picard wakes from a nightmare about his Borg kidnapping and assimilation, only to find the biomechanical race has just launched an offensive on Earth. The newly refurbished Enterprise-E races to the rescue and helps destroy the cube-shaped ship of the enemy, which at the last moment, launches an escape pod that flies back through time. Picard and crew follow, arriving in the twenty-first century to stop the Borg’s plan to wipe out humanity before it ever conceives of the Federation—specifically, the first warp-speed flight by Zefram Cochrane (James Cromwell), which led to the first meeting between the human race and the monitoring Vulcans. In essence, Cochrane’s mission means what Berman called “the birth of Star Trek.” Though the Borg fires a few shots at Earth, the Enterprise destroys their ship and apparently all Borg onboard. Now to assess the situation below. Visiting the war-torn Earth of the past, the disguised crew finds their hero Cochrane an insufferable, Honky Tonk-listening drunkard more concerned with making a buck than making history. The Borg attack damaged his shuttle, but Riker and engineer Geordi La Forge (LeVar Burton) assist a time-dizzy Cochrane to repair it and carry out his scheduled flight. For their future’s greater good, the crew breaks their Prime Directive to not interfere with the past or foreign civilizations, telling Cochrane who they are, when they’re from, and why they must help him.

Meanwhile, Picard and the android Data (Brent Spiner) return to the curiously incommunicado ship to give medical assistance to an injured past-earthling Lily (Alfre Woodard), unaware the Borg have made their way on the Enterprise during the commotion. Arriving on board, Picard faces his nightmare: The Borg are infiltrating his ship, moving methodically, logically, but also violently toward assuming control of the Enterprise. One by one, much like the mining party in Alien, the ship’s crew falls to an unseen foe making its way through ducts, converting enough crewmembers to lead a full-on takeover. Even Data is kidnapped and restrained, taken into the lair of the Borg leader, their Queen (Alice Krige), who tries to assimilate him—but not by their usual means. She wants him to surrender willingly to the collective by adding human flesh to his robot body, and she promises him countless other physical delights. As Data’s resolve falters, Picard’s loss of control over the ship forces him to consider detonating the Enterprise to stop the Borg. Lily, the Star Trek virgin’s entry point into the film, gets a Picard-guided tour through the fast-paced takeover and talks him down from his obsessive need to wipe the Borg out once and for all.

As Richard Corliss wrote in his Time magazine review, “Here is real acting! In a Star Trek film!” His enthusiasm is justified through Stewart, Woodard, and Cromwell’s performances. The former makes use of his prescribed theatrical training, at once embodying both Picard and Melville’s fanatical Ahab, adding depth to his already multilayered character. The situation finds Picard detached from his usual thoughtful, philosophical self, killing Borg drones mercilessly, and even putting half-assimilated crewmembers out of their misery though they might have been saved. When Lily confronts him over his passion for eradicating the Borg, the exchange amounts to the best acting the franchise has ever known. She accuses him of flat-out revenge, whereas Picard insists he’s only defending humanity, and that people from his future have an “evolved sensibility” that does not include revenge. “Bullshit! I saw the look on your face when you shot those Borg… You were almost enjoying it.” She adds, “Captain Ahab has to go hunt his whale.”

Well aware of her insinuation, Picard responds in a moment of bravura acting on Stewart’s part, his lips peeled back, his movements deliberate: “I will not sacrifice the Enterprise. We’ve made too many compromises already. Too many retreats. They invade our space, and we fall back. They assimilate entire worlds, and we fall back. Not again. The line must be drawn here! This far, no further! And I will make them pay for what they’ve done!” Although a similar Moby Dick parallel was made in The Wrath of Khan, it remains more appropriate in First Contact than in the earlier film. To be sure, the revenge-hungry Khan (Ricardo Montalbán) sought Kirk (William Shatner) after only a single episode of the original Star Trek series and was never again discussed before his appearance in the film. But the Borg have had a longstanding presence in The Next Generation; specifically, in the emotional turmoil they caused to Picard. Whether audiences were versed in the show or not, Picard’s scarred state from his experiences is thoroughly established in First Contact, and remains universal—a classical fear of losing one’s individuality to an industrial or foreign element, here represented by the Borg, a kind of amalgam of Soviet paranoia, technophobia, and zombiism.

Well aware of her insinuation, Picard responds in a moment of bravura acting on Stewart’s part, his lips peeled back, his movements deliberate: “I will not sacrifice the Enterprise. We’ve made too many compromises already. Too many retreats. They invade our space, and we fall back. They assimilate entire worlds, and we fall back. Not again. The line must be drawn here! This far, no further! And I will make them pay for what they’ve done!” Although a similar Moby Dick parallel was made in The Wrath of Khan, it remains more appropriate in First Contact than in the earlier film. To be sure, the revenge-hungry Khan (Ricardo Montalbán) sought Kirk (William Shatner) after only a single episode of the original Star Trek series and was never again discussed before his appearance in the film. But the Borg have had a longstanding presence in The Next Generation; specifically, in the emotional turmoil they caused to Picard. Whether audiences were versed in the show or not, Picard’s scarred state from his experiences is thoroughly established in First Contact, and remains universal—a classical fear of losing one’s individuality to an industrial or foreign element, here represented by the Borg, a kind of amalgam of Soviet paranoia, technophobia, and zombiism.

This fear is encapsulated in the scenes between the Borg Queen and Data. They contain layered, oddly disturbing dialogue and unnerving sexuality, unlike anything in Star Trek before. Under slimy, decayed-looking skin (the film earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Makeup), Krige radiates her character’s sexual appetite through that damp mechanical makeup; her lips and breathy voice are creepily alluring, her expressions demonstrating a kind of sadomasochistic pleasure from her body being torn apart and reassembled through mechanical parts. Watch her face as her human torso is lowered down and reconnected with her Borg frame. She seems to take orgasmic joy from rejoining with her artificial parts. These subtleties add to the conflict of Data’s potential defection, as his character has always desired to be human. Her proposal becomes even more alluring when she grafts skin onto his arm, caressing it and stimulating goosebumps. Many fans criticized First Contact’s continuity with The Next Generation series, claiming Krige’s character did not fit. The argument against the Borg Queen remains that, because the Borg were a hive mind and therefore not driven by any individual, it doesn’t make sense that the Borg would have an individual reigning over the collective. However, beyond the obvious ant metaphor, wherein each ant hive has a queen (see also Aliens), the Borg Queen character makes further sense after the series of episodes exploring Borg individuality in Seasons 5-7.

On Earth’s surface, the crew attempts to work alongside Cochrane and ensure the first human warp speed test goes as history intended, and the scenes provide much-needed comic relief from the tense situation in space aboard the Enterprise. Cromwell, a well-known actor who appeared in several episodes of The Next Generation in various roles, plays a glorious cad humbled and resistant to what he’s supposed to become. Of course, as the Borg might say, resistance is futile. Some of First Contact’s best moments occur between Cochrane and the Enterprise crew trying to convince him to carry out his plans since he feels overburdened by his looming place in history. After Cochrane feeds Deanna Troi (Marina Sirtis) “three shots of something called ‘tequila,’” she’s dead drunk, much to Riker’s amusement. “Timeline?” she says. “This is no time to talk about time. We don’t have the time.” Other crewmembers, like LaForge and the hapless engineer Lt. Barclay (Dwight Schultz), scare off Cochrane with tales of things he has yet to do. Still, by contrast, Cochrane represents a cultural launchpad—the great distance from which the seemingly enlightened people of the twenty-fourth century have advanced. He gets it eventually: “You people, you’re all astronauts on… some kind of star trek.”

Grossing $92 million in domestic receipts, among the most of any Star Trek picture, the film also received resoundingly positive reviews. In London’s The Independent, critic Ryan Gilbey wrote, “For the first time, a Star Trek movie actually looks like something more ambitious than an extended TV show.” As mentioned above, Corliss praised the acting, specifically Stewart, writing, “As he delivers [a] line with a majestic ferocity worthy of a Royal Shakespeare Company alumnus, the audience gapes in awe at a special effect more imposing than any ILM digital doodle.” These weren’t the typical sort of reviews for a Star Trek picture, as many critics didn’t see Star Trek: First Contact as another in the ongoing series, but rather as a fresh entry point for the inexperienced and a solid film on its own merits. Much in the way that 2009’s Star Trek amassed fans that might never have watched such a film, the scenario speaks to anyone through its pace and simplicity. The plot may involve complex ideas of time travel, the Borg, and the general futurist setting, but the technical jargon remains at a minimum, leaving the conflict to arise through concise cinematic language so that anyone can grasp the stakes, no matter their experience with Star Trek.

Never mind how easily time travel or the Borg’s infiltration are accomplished, because that’s not the concern—what matters is how effortlessly the experience flows as a piece of entertainment, as well as Star Trek canon. Braga and Moore contrast an alien invasion on the Enterprise with the launch countdown on Earth, balancing thrills with light humor and suspense, a perfect concoction for general audiences. Equaled only by The Voyage Home and J.J. Abrams’ revision, Roddenberry’s creation has seldom been so accessible. Star Trek: First Contact represents a remarkable and uncommon occasion where the franchise chooses to be more than another space opera, and instead, it advances into a cinematic breakthrough. Frakes’ effort earned its keep not by presenting just another entry into a series, but by completing a work that transcends the fandom and cultural phenomenon, and succeeds in being just a great film.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review