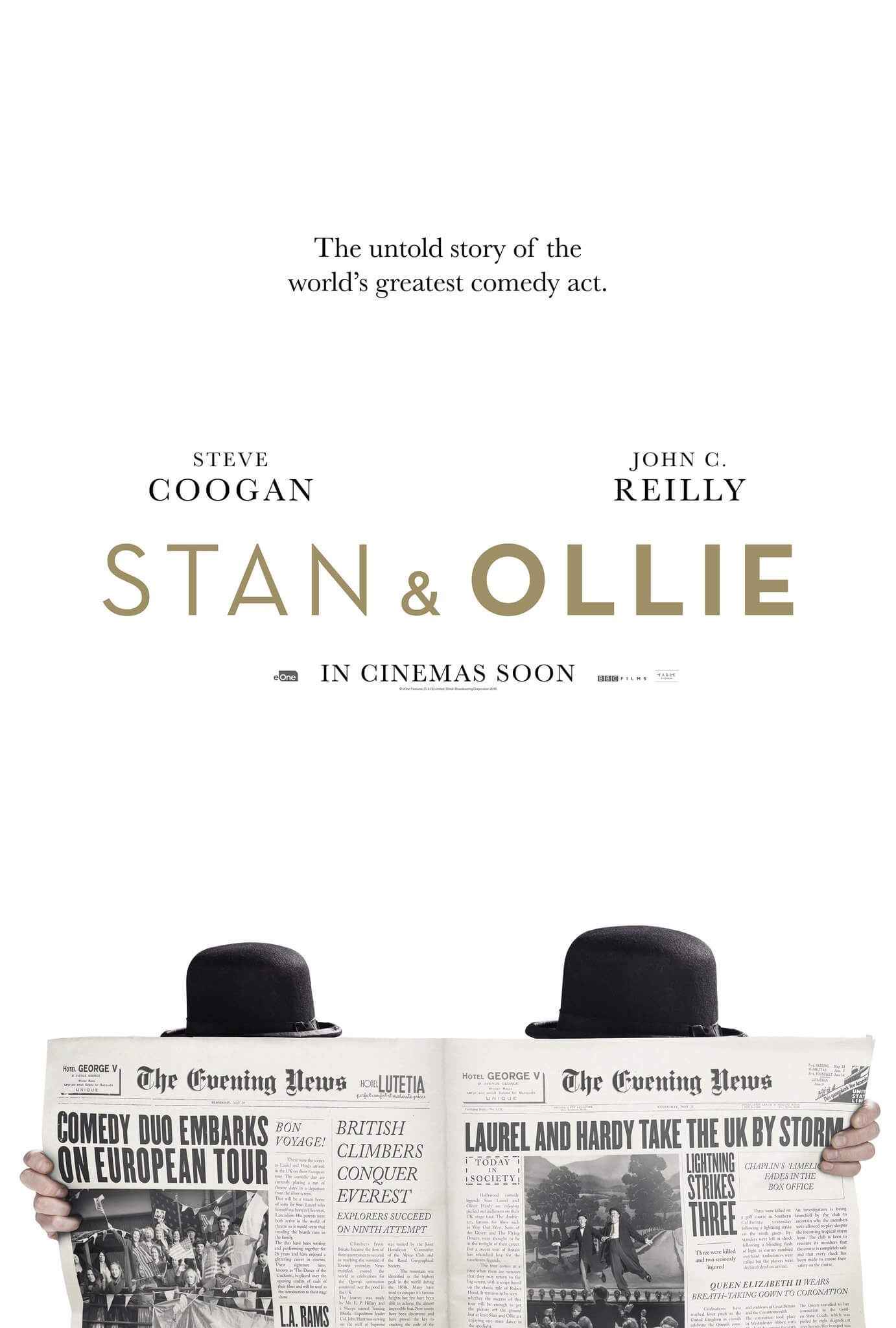

Stan & Ollie

By Brian Eggert |

Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy may occupy the fourth-rung of vaudeville comedians to become stars of the silver screen, but that shouldn’t dimish their genius. They didn’t have the sublime artistry or obsessive creative control of Charlie Chaplin, whose independently made Little Tramp pictures showcased his loveable scamp in hilarious but also heartrending situations. They didn’t have the large-scale technical virtuosity of Buster Keaton, whose stone-faced presence performed some of the most incredible stunt-gags ever captured on film. Nor did they have Harold Lloyd’s humanism that, by merely following the desires of the everyman, found him in oodles of trouble. What Laurel and Hardy had was great chemistry; their slapstick and wordplay routines remain timeless, putting Abbott and Costello to shame. Best of all, they maintained a direct relationship with the audience. For every mix-up or blunder that befalls the rotund Hardy on account of his thinner, absent-minded partner, he looks directly into the camera, connecting with the audience as a vaudeville performer might, and shares his exasperation and disdain. “Well, here’s another nice mess you’ve gotten me into.”

Stan & Ollie lovingly captures their talent, their personal mannerisms, and the enduring joy of their comedy by way of Steve Coogan and John C. Reilly, well-known actors who play well-known actors. Both disappear into their roles thanks to convincing make-up effects—Coogan behind an elongated chin to create Laurel’s signature grin, and Reilly underneath a suit that fills out Hardy’s girth. Within seconds of the film’s start, the viewer forgets about Coogan and Reilly, however, and sees only Laurel and Hardy returned to the screen more than five decades after their passing. It’s not so much an impersonation as a spiritual and physical embodiment. Coogan brilliantly recreates Laurel’s blinks, shrugs, and nasally British voice, while Reilly has the cadence, Humpty walk, and faint Georgian accent down perfectly. It’s a shame this late 2018 release didn’t receive more awards attention from the Oscars, Golden Globes, or Screen Actors Guild; these are two of the most fully realized portraits of real-life people in recent memory.

Director John S. Baird works from a script by Jeff Pope, based on A.J. Marriot’s book from 1993, Laurel and Hardy: The British Tours. Situated in the mid-1950s, some sixteen years after the team split over a contract dispute between Laurel and their longtime producer, Hal Roach (Danny Huston), the film’s setting is a curious choice. It doesn’t find the comedians in their workhorse prime between the late 1920s and early 1930s, when it wasn’t unheard of to release upwards of fifteen short films and a feature in the expanse of a single year—when they were household names and unwavering box-office draws. It finds both men post-prime and hoping to rekindle their former glory by proving their brand of comedy still has appeal with a British stage tour. Booked at a series of modest venues by their unconvinced British producer Bernard Delfont (Rufus Jones), the pair, now in their sixties, steps back into familiar patterns, hoping to earn enough attention to get a new comedy about Robin Hood greenlit in Hollywood.

Laurel, ever the creative force and gag writer, toils behind a typewriter, refining and perfecting every comic scene’s meticulous timing. Hardy, always amused by his partner’s ideas, struggles to control his weight and gambling problems. Both men have put alcohol and several divorces behind them. And they receive regular scoldings from their current wives—Lucille Hardy (Shirley Henderson) and Ida Kitaeva Laurel (Nina Arianda), who remain in America while their husbands rediscover their footing. Fortunately, the wives, once they arrive in the U.K., prove to be more than a mere nagging force; they’re loving and dimensional characters that give way to a deeper relationship with these men. Meanwhile, alone together, Laurel and Hardy perform for sparse crowds until, gradually, after several promotional appearances, they’re back in the spotlight and selling out shows. But the dynamic between them extends beyond the stagecraft and comic effort; there’s a history full of bruised egos, lost opportunities, and blame to explore.

Laurel, ever the creative force and gag writer, toils behind a typewriter, refining and perfecting every comic scene’s meticulous timing. Hardy, always amused by his partner’s ideas, struggles to control his weight and gambling problems. Both men have put alcohol and several divorces behind them. And they receive regular scoldings from their current wives—Lucille Hardy (Shirley Henderson) and Ida Kitaeva Laurel (Nina Arianda), who remain in America while their husbands rediscover their footing. Fortunately, the wives, once they arrive in the U.K., prove to be more than a mere nagging force; they’re loving and dimensional characters that give way to a deeper relationship with these men. Meanwhile, alone together, Laurel and Hardy perform for sparse crowds until, gradually, after several promotional appearances, they’re back in the spotlight and selling out shows. But the dynamic between them extends beyond the stagecraft and comic effort; there’s a history full of bruised egos, lost opportunities, and blame to explore.

The 97-minute film unfolds over the course of their tour, but it feels all the more downtrodden and humble after the dazzling opening sequence. Stan & Ollie begins with a brief prologue set in 1937 as Laurel and Hardy shoot one of their best and most successful features, Way Out West. The unbroken extended take, filmed with bravado Steadicam lensing by Laurie Rose, lasts several minutes, escorting the viewer through a familiar backlot scene—extras in costumes, technicians fussing with equipment, bustling open sets, and Hollywood artifice exposed. After this, the drab music halls across the U.K. reflect their fallen status. To be sure, more people watched Laurel and Hardy shorts on television in the 1950s than in movie theaters. And on their tour, most of the (elderly) fans they meet believed they had retired or were dead. The contrast sets the melancholy tone for the film, which is frequently interrupted by Coogan and Reilly’s uncanny re-creation of the duo’s stage act.

Baird’s past work doesn’t suggest he would be the right choice for Stan & Ollie. He’s made a couple of tough British crime films, such as Cass (2008) and Filth (2013), but nothing so richly textured and certainly not this comedic. Yet, production designer John Paul Kelly and costumer Guy Speranza recreate the specific world of Laurel and Hardy’s tour from archival photographs, many of them featured over the end credits. The mise-en-scène is immersive, to the extent that the viewer stops relishing every visual detail and accepts them as the onscreen reality. This extends to the outstanding work by Coogan and Reilly, who capture the essence of Laurel and Hardy’s comedy—especially in the “two doors” bit, an amazing piece of comic persona and timing. But their comedy reaches beyond the stage into small improvisations on the publicity tour or in a waiting room, suggesting these two men were masters of their distinct brand at any given moment. If there’s a single sour note in Stan & Ollie, it’s Rolfe Kent’s generic score.

In another film, I might be skeptical about the stage performance scenes in which Baird cuts to a full audience cackling at Laurel and Hardy’s routine. We see riotous laughter and applause that elsewhere might seem over-the-top. However, I recently screened a series of their restored two-reelers in a packed theater and, much to my delight, the audience reacted similarly to what’s depicted in Stan & Ollie. It was overwhelming. Whether it was in the 1920s during their prime, the 1950s amid their swan song, or half a century later in an Alamo Drafthouse, Laurel and Hardy could make people laugh—and not just a wide grin or muffled chuckle, but a hearty belly laugh, the kind that zeroes-out all other sounds and infects the viewers around you. Coogan and Reilly’s astonishing recreation of their humor is just as funny as the real thing. It’s all the more impressive that Stan & Ollie, while a testament to these artists, also supplies a bittersweet portrait of two colleagues who finally realize that they’re best friends. With any luck, the film will inspire renewed interest and consideration of their work by serious film scholars, positioning them where they belong, alongside the likes of Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review