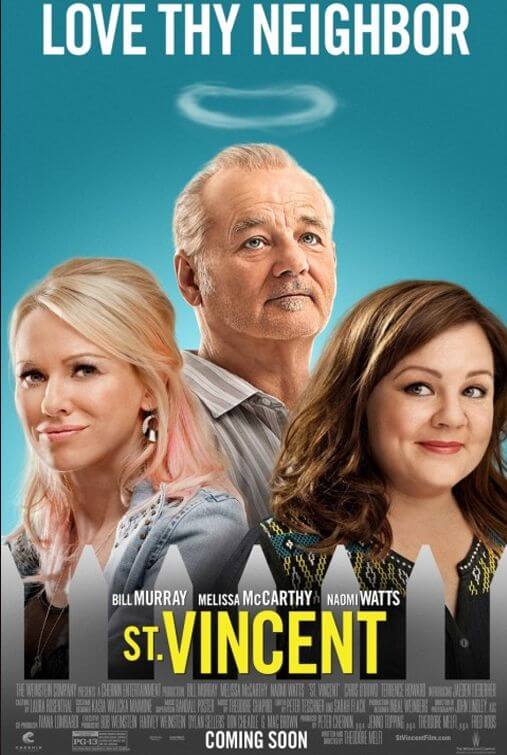

St. Vincent

By Brian Eggert |

Children who are lonely outsiders often buddy up with cantankerous old farts in offbeat indie comedies and idiosyncratic feel-good fare like The Royal Tenenbaums, Little Miss Sunshine, Up, and now St. Vincent. First-time feature director Theodore Melfi doesn’t miss a beat copying those dramedies about the bond between a child and an irascible coot in his festival favorite, which makes good use of Bill Murray’s finest strengths as a comedian and actor. Designed to rouse belly laughs and instill some tears too, the plotting may be predictable and, in the end, manipulative in a transparent way, but the strong performances from Murray and Melfi’s excellent supporting cast allow us to forgive St. Vincent‘s more obvious sentimental intentions.

Murray stars as the mean and ornery Vincent, a misanthrope who lives alone with his cat Felix and considers his only friend the Russian prostitute Daka (Naomi Watts), who visits once a week. Moving in next to Vincent’s dilapidated home are a single mother, Maggie (Melissa McCarthy), and her young son, Oliver (Jaeden Lieberher). She’s recently left her cheating husband and resolved to raise Oliver herself. But when her movers break a branch off Vincent’s tree, the grumpy old man demands financial satisfaction. After all, he’s broke and hounded by his bookie’s collector (Terrence Howard), and he can barely afford to pay Daka, who’s pregnant. What’s more, Vincent lives on a diet of sardines, saltines, and booze. With Maggie in a bind for a babysitter, she asks Vincent to watch Oliver, and after negotiating a $12-an-hour salary, he begrudgingly agrees.

Oliver is sweet, skinny, and smart, and so he’s picked on in school. Hanging around with Vincent teaches him a few tricks, not the least of which are fighting and swearing. Vincent’s idea of babysitting involves trips to the racetrack and bar, which come up later during Maggie’s custody hearing. But central to St. Vincent is the friendship that blossoms between Vincent and Oliver. Despite his cranky exterior, Vincent shows his vulnerable side when he brings Oliver to visit an Alzheimer’s-afflicted woman in a nursing home, who we learn is Vincent’s wife. And there’s more to learn and observe about the character, all of which newcomer Jaeden Lieberher does wonderfully. He’s never stiff or forced the way some child actors are, and his pairing with Murray seems naturalistic throughout.

Aside from some questions about how Vincent manages to pay the costs of living, support Daka, and cover countless other costs, Melfi also mishandles a few unresolved subplots. Is Vincent the father of Daka’s baby? After they disappear in one scene, we have to wonder what happens to the bookies Vincent owed? Why is Oliver’s father so easily forgiven later in the film? None of these story elements are thoroughly explored, but by the final scenes, it hardly matters. In the third act, Oliver’s engaging teacher (Chris O’Dowd) assigns everyone in the class a project called “Saints Among Us,” where they must pick someone in their lives who’s worthy of sainthood. By the title, it’s obvious who Oliver chooses. And Oliver’s final assembly hall speech about the deeply human, deeply flawed character Murray plays cannot help but make us tear up, even if we know we’re being maneuvered. It’s an effective moment that fills us with shame for allowing the filmmakers to operate us so.

Nevertheless, it’s a joy to watch Murray perform his deadpan irritation routine to comic effect, but also touch some sour notes that prove cutting. Melfi’s film works because his casting is flawless. Even McCarthy—who has overstayed her welcome in her typecast I’m-fat-and-I’ll-say-anything-for-a-laugh routine from Bridesmaids, The Heat, Identity Thief, and Tammy—plays against type as a pained, struggling single mother. Watts also seems to be having a great deal of fun playing a thick-accented and trashy hooker-with-a-heart-of-gold. But, again, it’s Murray and Lieberher’s show, and their warmhearted friendship becomes the stuff of schmaltziness, yet only after plenty of inappropriate humor and situations. The overall result of St. Vincent is an endearing if sappy feel-gooder made pleasant by the affable presence of Bill Murray.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review