Spotlight

By Brian Eggert |

For about the last forty years, every film about journalists investigating a complicated, world-shattering story receives comparisons to All the President’s Men. The 1976 Alan J. Pakula classic featured Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman as Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, the reporters who uncovered the Watergate scandal that led to President Nixon’s resignation. Many titles deserve such a comparison, such as David Fincher’s Zodiac (2007), a film about obsession over San Francisco’s Zodiac killer case that modeled its newspaper room scenes after those in Pakula’s film. A more recent example is 2015’s Truth, about 60 Minutes producer Mary Mapes’ investigation into President George W. Bush’s suspicious military record, a story that ended with Dan Rather’s resignation. None of the imitators have so craftily adopted the structure and energy of Pakula’s film, until Tom McCarthy’s at once thrilling and aching Spotlight, that is.

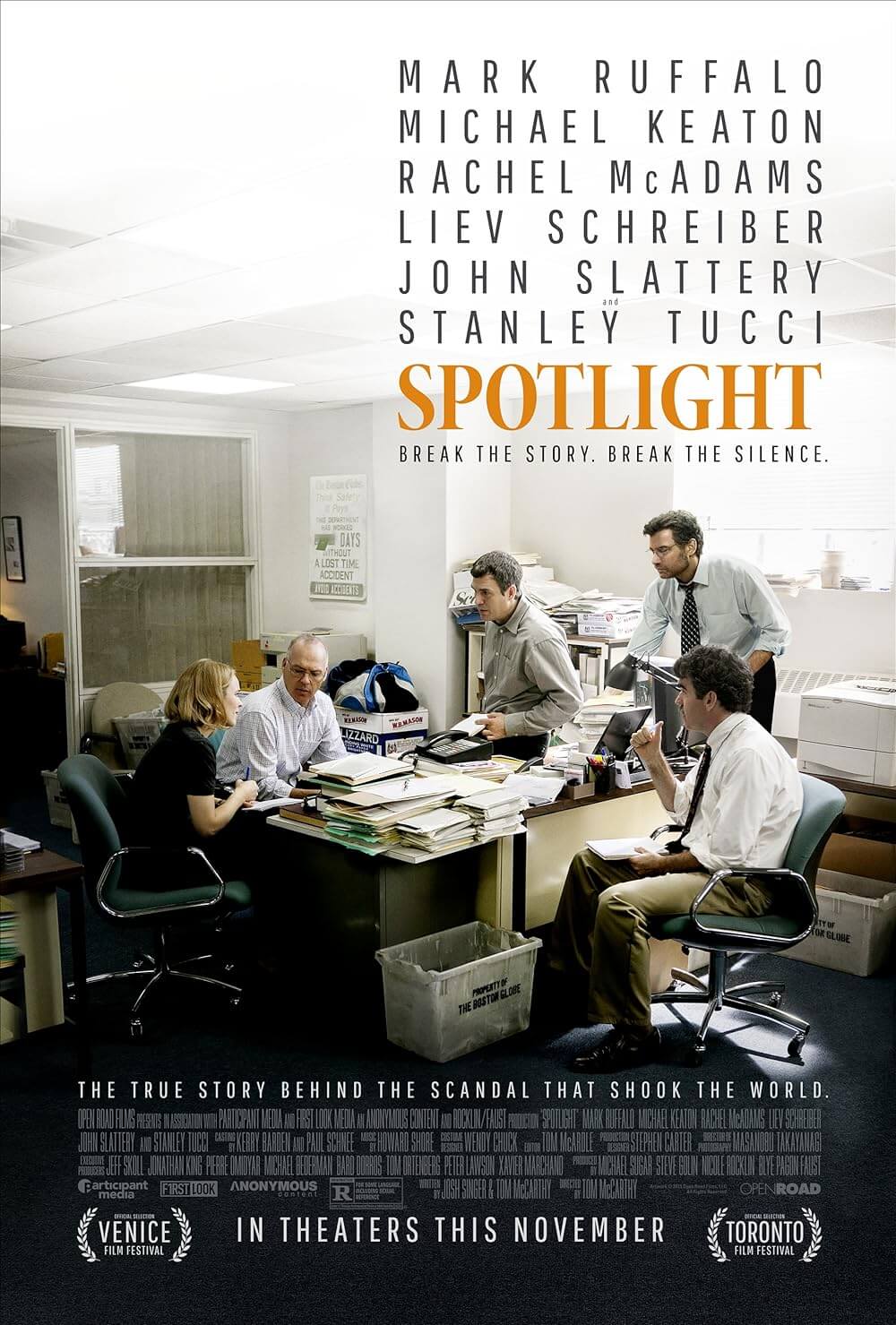

Directed by McCarthy (The Visitor) from a script he co-wrote with Josh Singer, Spotlight creates a filmic exposé out of the Catholic Church’s unsettling history of pedophilia and concealment thereof, while also questioning the morality of an institution that endeavors to cover it up. Employing that same slow-build method of All the President’s Men, McCarthy’s sobering drama affects on multiple levels, from personal to spiritual. The real-life Pulitzer Prize-winning investigation by The Boston Globe exposed a corrupt institution and the seemingly brainwashed community of Boston that suppressed it. But the film also points to a much larger, worldwide epidemic of sexual abuse conducted and systemically covered-up by the Church. And quite unlike the comic anger with which Philomena (2013) targeted the Church, Spotlight‘s integrity toward its subject makes the material all the more disquieting.

The title Spotlight refers to the investigative section of The Boston Globe, which might spend several months to over a year on a single story. Headed by go-getter Walter Robinson (Michael Keaton), the foursome also features squirrelly writer Mike Rezendes (Mark Ruffalo), family man Matty Carroll (Brian d’Arcy James), and thorough investigator Sacha Pfeiffer (Rachel McAdams). While searching for a new story under his managing editor Ben Bradlee Jr. (John Slattery), Walter receives his assignment from the Globe‘s new editor-in-chief, Martin Baron (Liev Schreiber). Having just arrived in Boston from a posting at The Miami Herald, Baron, a Jewish man in a city of Irish Catholics, does not shy away when he reads a recent column the Globe ran about a local priest accused of abusing children. He wonders if there could me more stories like this out there, and he devotes the “Spotlight” team’s resources to the investigation.

Meanwhile, Baron discovers the kind of landscape that has kept these secrets so well. “The city flourishes when its great institutions work together,” Cardinal Law (Len Cariou) tells Baron, at an obligatory meeting between any new Globe editor and the Cardinal, no less. There’s a lot of that going around Boston, the reporters find: people in high places turning a blind eye, or the family and friends of victims encouraging the abused to remain silent for the greater good. You begin to wonder how these people could consider such a matter is best-kept secret, but that’s what unshakable faith in an institution of flawed men gets you. It’s also common practice to turn away from unpopular stories; sadly, they discover sex scandals in the religious ranks have been buried by the Globe before. Nevertheless, by the film’s conclusion, a coda tells us over 600 stories were eventually written about the scandal by the “Spotlight” staff.

Utilizing his cast of character actors, McCarthy resists going too far into the personal lives of these journalists and never diverts away from the central story. The actors’ unique idiosyncrasies, such as Keaton’s puckered lips or Ruffalo’s cocked mouth, add small yet significant quirks that create the illusion of character depth. Not much about the characters’ lives appears onscreen, but the excellent performances make it seem like we’re seeing more than we are. Elsewhere, in dueling lawyer roles, Billy Crudup plays a slippery defender of these priests, while Stanley Tucci plays a busy crusader who devotes his life to doing the right thing—a particularly difficult quality to come by in this setting. Fortunately, McCarthy’s polished direction and script refuse to paint the Globe as heroic journalists free of blame. Boston’s community of suppression and exertion of influence extends to the media as well; fortunately, what remains important is telling the truth in the here and now.

Only one scene stands out from McCarthy’s otherwise uniform direction, but it stands out in a good way. It’s a moment when Rezendes stands watching, with a wounded look on his face, as a church choir sings “Silent Night” around Christmastime. His concern for their safety is an overwhelming blow to the viewer, but then so is the likelihood that one of the choir’s young singers has been preyed upon. This moment offers one of Spotlight‘s rare moments away from the investigative throughline, as the film remains almost exclusively, and admirably, from the reporters’ perspective. McCarthy’s sensitivity for the subject never steps over a line by depicting the actual abuse; instead, he leaves us with the haunting probability evoked through Ruffalo’s grim expression. And when the film comes to an end, the postscript tells us more than 1,000 victims came forward in Boston alone. More staggering still, McCarthy shows us several lists, row upon row of cities in which similar, large-scale scandals have been uncovered. The number of these cities is staggering, and the viewer cannot help but quickly scan to see if their hometown or state is mentioned among them.

Spotlight saturates the viewer with mountains of true details about actual cases, as reporters listen to the heartrending stories of victims. One “Spotlight” source, a former psychoanalyst for the Church (voiced by Richard Jenkins) who ran a recovery center for predatory priests and their victims, says 6% of all priests have a psychosexual condition that turns them into pedophiles. When Pfeiffer interviews one such priest at his home, he seems assured for some reason that his predatory habits were not rape (“Sure, I fooled around, but I never felt gratified myself,” he says). His confession hints that the involved process by which the Church shuffled him around the country and coached him developed into this morbid justification. If McCarthy and his film achieve anything more grandiose than an expert, engrossing drama, which they do, it’s the film’s depiction of a world shattered. The concept of a stable community, an unwavering house of the “Lord,” and a certainty of faith comes crumbling down—inextricably brought into question when something as big and awful as this is uncovered. That feeling stays with you long after Spotlight is over.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review