Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse

By Brian Eggert |

“Let’s do things differently this time,” Gwen Stacy declares in the opening of Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse. Better known as Ghost-Spider and voiced by Hailee Steinfeld, the character promises the Into the Spider-Verse sequel will turn everything on its head. The 2018 original made similar promises, but for all its glorious advances in animation, it conformed to a typical superhero origin story: the young monomythic hero learns about his world, expands his abilities, and applies his new skills against a climactic villain to arrive at a place of self-discovery. While the scenario was complicated by the multiverse and several onscreen Spider-Man variants, all of which allowed for more inclusivity, the basic structure broke no significant storytelling rules. The sequel follows this pattern with even more dazzling formal breakthroughs. However, the more you look at the film’s overall structure, the more it becomes apparent that the narrative resembles standard Hollywood conventions for the second entry in a trilogy. Rather, it’s the specifics—the character identities, the varied animation styles, the overall aesthetic schema—that break the mold. And so, when Gwen doubles down by promising, “If you think you know the rest, you don’t,” her avowal may not quite apply to every aspect of Across the Spider-Verse.

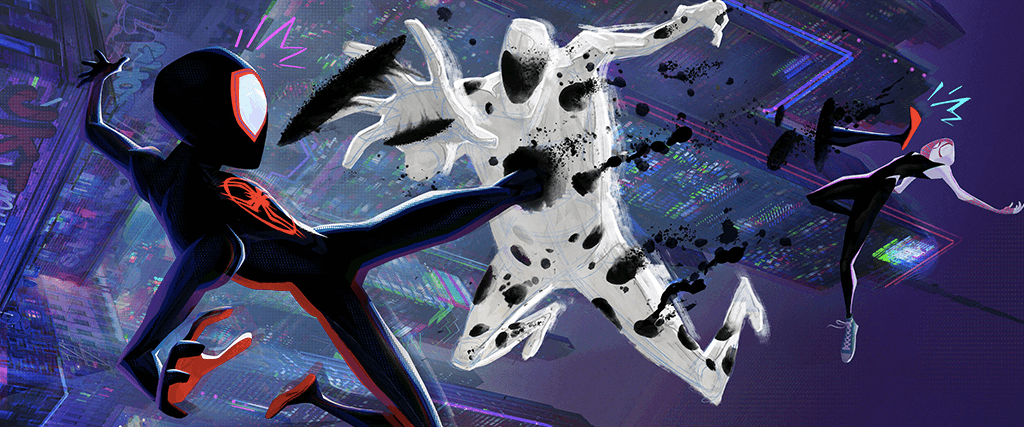

Made by three credited directors (Joaquim Dos Santos, Kemp Powers, Justin K. Thompson) and a trio of writers (Phil Lord, Christopher Miller, David Callaham), the production represents, unsurprisingly, a collaborative effort. But the celebrity voice talent and above-the-line crew aren’t the stars; the hundreds of animators who worked on Across the Spider-Verse are. Take away the stunning array of styles and visual energy on display, which alternate as the mood and situational expressivity compel them, and the sequel is standard mid-trilogy stuff: darker, more complicated, higher stakes, and deeper emotions—all capped by a grim cliffhanger finale. Fortunately, Across the Spider-Verse is a visually loaded film. Every scene contains countless details, from amusing visual gags to exposition boxes popping up onscreen. The wide-ranging character and world designs include styles that resemble impressionistic watercolors, comic-booky Ben-Day dots, sketch-like hand-drawn figures, erratic collages, expressionist monochrome inks, blocky stop-motion, and even live-action. But as the story moves in predictable directions, the animation brings every character and situation to vivid life.

The story involves Gwen and Miles Morales (Shameik Moore) grappling with their respective parents in tender subplots while also confronting the vast complexities of the Spider-Verse. It turns out that Miles inadvertently created a new baddie, named The Spot (Jason Schwartzman), who can open inter-dimensional portals. Out for revenge, The Spot targets Miles and, in a rather uncompelling motivation, is determined to become more than a “villain of the week.” That no one takes this initially goofy villain seriously in the film’s first half—including the viewer—means the stakes depend more on interpersonal conflicts. After Gwen reveals to her father, Captain Stacy (Shea Whigham), that she’s Ghost-Spider to a disastrous response, she warns Miles not to tell his affable parents (Luna Lauren Vélez, Brian Tyree Henry) about his superhero alter-ego. But they’re increasingly concerned about their son, who seems to be hiding things and distracted lately. No wonder, since Miles finds out there’s a multiverse collective of Spider-People who, together, serve as police for the integrity of the Spider-Verse.

Of course, Across the Spider-Verse might also hold the biggest basket of Easter Eggs ever collected by Hollywood in one film. Given the story’s multiverse backdrop, the filmmakers exploit the opportunity to include practically every iteration of the web-slinger to appear in comic books, movies, and animated series. Since Easter Eggs derive from video games, which often provide an in-game reward for their discovery, accompanied by a visual flash and an aural bing, much of the film’s audience is hardwired to feel a burst of endorphins from uncovering them. So when Miles’ roommate Ganke (Peter Sohn) plays the excellent 2018 Spider-Man game in a self-reflexive wink, a live-action actor shows up as The Prowler, or the vintage 1980s cartoon version of Spidey appears, the viewer receives a Pavlovian buzz. It’s a cheap but effective trick. This also creates a sense that the filmmakers know the intellectual property as much as the die-hard fans, prompting waves of pleasure from knowing it’s a fan-created product and every detail in the background has been placed with care. But it would be too easy to dismiss this quality as pandering to the fanbase (which it does); the multiversal story requires variants, suggesting their inclusion is functional too.

Of course, Across the Spider-Verse might also hold the biggest basket of Easter Eggs ever collected by Hollywood in one film. Given the story’s multiverse backdrop, the filmmakers exploit the opportunity to include practically every iteration of the web-slinger to appear in comic books, movies, and animated series. Since Easter Eggs derive from video games, which often provide an in-game reward for their discovery, accompanied by a visual flash and an aural bing, much of the film’s audience is hardwired to feel a burst of endorphins from uncovering them. So when Miles’ roommate Ganke (Peter Sohn) plays the excellent 2018 Spider-Man game in a self-reflexive wink, a live-action actor shows up as The Prowler, or the vintage 1980s cartoon version of Spidey appears, the viewer receives a Pavlovian buzz. It’s a cheap but effective trick. This also creates a sense that the filmmakers know the intellectual property as much as the die-hard fans, prompting waves of pleasure from knowing it’s a fan-created product and every detail in the background has been placed with care. But it would be too easy to dismiss this quality as pandering to the fanbase (which it does); the multiversal story requires variants, suggesting their inclusion is functional too.

Still, it’s difficult not to feel that Sony has found a way to splice multiple eras of Spider-Man fandom into a single entity, mirroring the crossover synergy of similar pictures such as Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), which brought together Looney Tunes and Disney characters (or, if you prefer, last year’s Chip and Dale’s Rescue Rangers, an ode to decades of animation). Spider-Man has been part of the culture since the 1960s; the character has changed and connected with generations in various iterations. Some of us love the 1990s animated series, others will always see Tobey Maguire behind the mask, and others still prefer one of the many comic book offshoots (most of which appear in this movie). In recent years, Sony has further fractured and expanded the Spider-Man brand with a cinematic universe unto itself, resulting in the antihero spin-offs such as Venom (2018) and Morbius (2022), with more to come. Across the Spider-Verse gives most of these individual brands their due, if only for a microsecond in some cases, ensuring that everyone in the audience, young and old, sees their favorite Spider-Man represented onscreen.

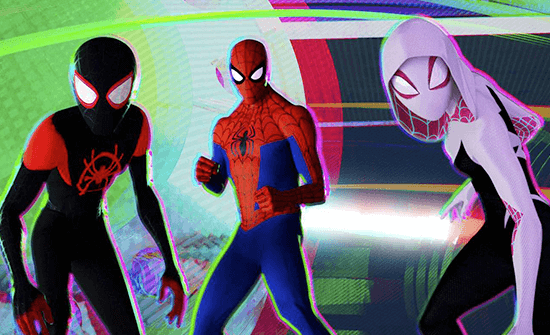

It’s tempting to dismiss these choices as pecuniary. Yet, they prove ingenious and aligned with Across the Spider-Verse’s inclusion theme, where, in the multiverse, anyone can be Spider-Man—not just white males like Peter Parker. Besides Miles and Gwen, the movie features an Indian hero (Karan Soni) from the distant future, where Mumbai and Manhattan have merged; a Black version of Spider-Woman (Issa Rae), who’s pregnant and rides a motorcycle; and the best addition, Hobie (Daniel Kaluuya), a British punk Spider-Man who embraces chaos in all its forms. However, like its predecessor, the sequel doesn’t trust its audience to interpret its inclusive message, so the characters telegraph it in obvious dialogue. In Gwen’s bookend narration, she addresses the viewer and ultimately invites everyone to join her band of Spider-rebels. If it’s ham-fisted in the method of its welcoming message, the effect cannot be faulted as a rallying cry to an audience that, no matter their race, gender, or ethnicity, will likely feel seen.

The filmmakers take the notion even further by questioning traditional story structures within the diegesis by introducing a canonical web that links all Spider-People by their similar experiences. According to the rules, all Spider-People must have gone through certain canonical events, such as the loss of Uncle Ben, the doomed romance between Spider-Man and Gwen Stacy, or the death of Captain Morales. At least, that’s according to the “Spider Society” overseer, Miguel O’Hara (Oscar Isaac), better known as Spider-Man 2099—a high-tech vampire hero who monitors the Spider-Verse in a role analogous to the Time Variance Authority in the MCU’s Loki series. These tangled particulars become somewhat overfamiliar in their deployment of the multiverse, multiverse cops, and those who refuse to conform to their rules. With similar ideas driving Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021), Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022), and the recent winner of the Oscar for Best Picture, Everything Everywhere All at Once, the novelty of multiverses, hero variants, and multiverse police has started to feel overplayed, both in superhero movies and beyond.

The filmmakers take the notion even further by questioning traditional story structures within the diegesis by introducing a canonical web that links all Spider-People by their similar experiences. According to the rules, all Spider-People must have gone through certain canonical events, such as the loss of Uncle Ben, the doomed romance between Spider-Man and Gwen Stacy, or the death of Captain Morales. At least, that’s according to the “Spider Society” overseer, Miguel O’Hara (Oscar Isaac), better known as Spider-Man 2099—a high-tech vampire hero who monitors the Spider-Verse in a role analogous to the Time Variance Authority in the MCU’s Loki series. These tangled particulars become somewhat overfamiliar in their deployment of the multiverse, multiverse cops, and those who refuse to conform to their rules. With similar ideas driving Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021), Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022), and the recent winner of the Oscar for Best Picture, Everything Everywhere All at Once, the novelty of multiverses, hero variants, and multiverse police has started to feel overplayed, both in superhero movies and beyond.

Moreover, the filmmakers seem so enthralled by the endless possibilities that they’ve crammed oodles of story into a 135-minute feature, which is bound to leave most viewers exhausted—hopefully in a good way. Like many superhero movies today, Across the Spider-Verse, quite appropriately, adopts a structure that disposes of the conventional three-act model and instead divides the second act into multiple individual acts. Recent blockbusters use this model to give the movie a sense of epic scope and plot intricacy. Here, the narrative layering builds toward a cliffhanger finale that will be resolved with next spring’s Beyond the Spider-Verse. Meanwhile, the sequel follows in the tradition of The Empire Strikes Back (1980)—the trilogy template that inspired the down-note endings in The Dark Knight (2008), The Desolation of Smaug (2013), and The Hunger Games: Catching Fire (2013)—complete with a “Luke, I am your father” twist. The specifics of the finale aren’t predictable. But the part-two setup that leads to a final chapter adheres to the Hollywood trilogy template in a manner that proves disappointing for a film thematically committed to disrupting archetypes.

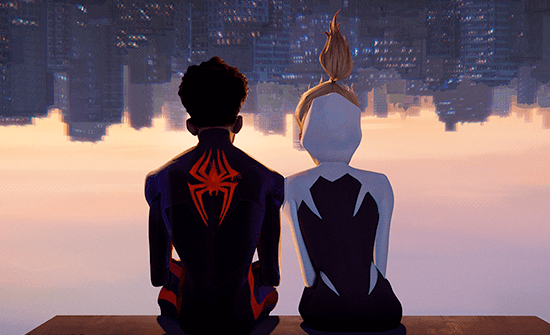

Setting aside its predictable sequel structure and tired multiverse milieu, Across the Spider-Verse offers a wealth of energy, humor, well-drawn characters, and inspired animation. Just when its elaborate web-slinging battles start to run on too long, the filmmakers slow things down for affecting scenes between Miles and Gwen or Miles and his parents, which remind us why we’re so invested in the action. It’s an unquestionable fan-pleaser, bound to tickle Spidey devotees with its bottomless font of meta-humor and self-awareness, spanning many Spider-Man iterations on television and film. Surely, it deserves to be called a step forward from its predecessor. The animation alone pushes the already impressive boundaries established by Into the Spider-Verse, achieving new heights that have set a new Hollywood benchmark for the form. The full consequence of Across the Spider-Verse cannot be fully assessed until the trilogy wraps, but until then, this is an entertaining and ambitious sequel.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review