Reader's Choice

Spider

By Brian Eggert |

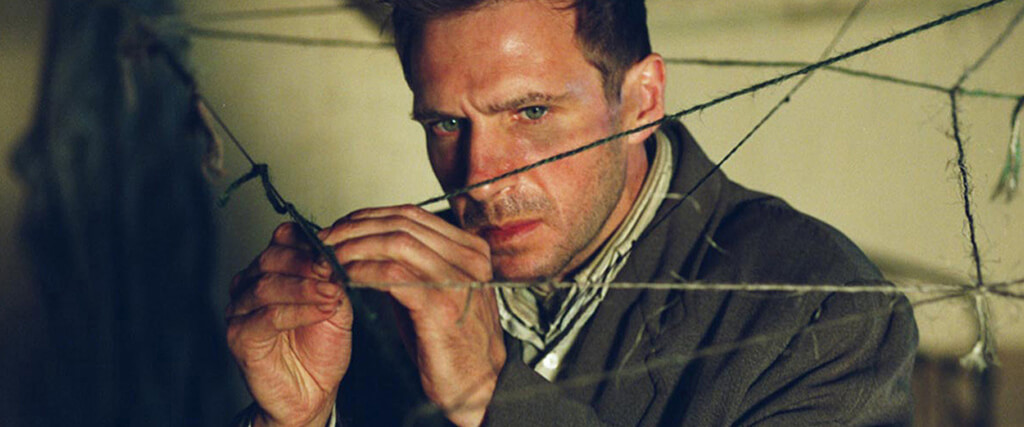

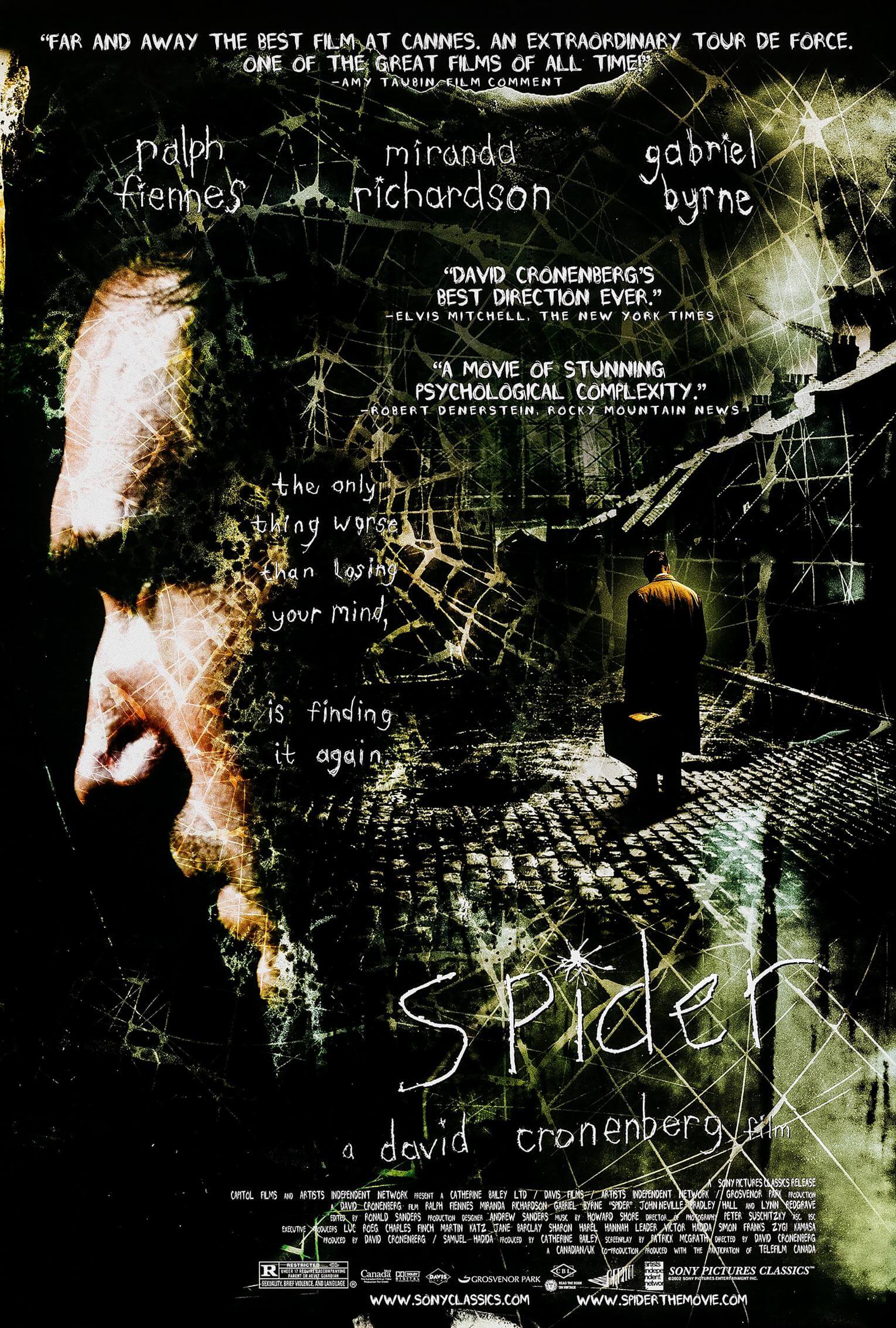

Spider is among Canadian director David Cronenberg’s most underseen, underrated, and yet sophisticated pieces of filmmaking. Released in 2002 and mostly overshadowed as of this writing, the film marks a transitional point in Cronenberg’s career, shifting away from his obsession with body horror and mind-body dichotomies into a focused interest in the psychological, which would preoccupy his career for the next twenty years. Based on Patrick McGrath’s 1990 novel of the same name, the adaptation occupies the patchwork mind of Dennis Cleg, played by Ralph Fiennes. A new arrival at a halfway house for the mentally disturbed after his stay in a psychiatric institute, Dennis, who goes by the titular nickname, weaves the loose strands of his memory and recreates them in his imagination. Strand by strand, he spins an understanding of his repressed trauma—the memory of a murder. McGrath wrote the screenplay, and Cronenberg explores the protagonist’s severe interiority through a subtle visual schema, supported by Fiennes in an understated and brilliantly committed performance of mumbles and micro-gestures. Spider unfolds through the lens of Dennis’ disturbed mind, fractured by Freudian neuroses. No other film in Cronenberg’s career has felt so entrenched in his protagonist’s subjectivity.

Generally, Cronenberg’s cinema lends itself to psychoanalytic readings; after all, he made the Carl Jung and Sigmund Freud drama A Dangerous Method (2011). But he’s literate and conscious about such matters, insomuch that he seeks out material that interests him intellectually. And if his earliest interviews as a filmmaker—rife with discussions of psychoanalytic theory—give any indication, his intellectual perspective has informed his work since his earliest body horror B-movies. Yet, no Cronenberg film lends itself to a psychoanalytic reading more than Spider. Its drama plays out with an almost textbook understanding of Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams, where the psychoanalyst discusses the inherent “psychical impulses” of children toward their parents—better known as the Oedipus Complex—and how, if not properly disconnected, the impulses can form into neuroses later in life. Freud argues these impulses take the form of a sexual desire toward mothers and hatred or jealousy toward fathers. Though scholars have questioned the legitimacy of the Oedipal Complex given Freud’s typically male-centric gender perspectives, Cronenberg’s film presents a character who exemplifies Freud’s theory. Dennis continues his obsessional impulses toward his parents into adulthood; because he does not dismiss these impulses, he becomes, as Freud would argue, “psychoneurotic”—what today would be labeled as an individual suffering from an emotional disorder.

Spider is a rare Cronenberg film that shows interest in parent-child dynamics. Not since The Brood in 1979 had the director explored the trauma parents can inflict on their children, and Spider takes place around that same period—indicated by a café sign that says “Keep Britain Tidy,” a 1970s slogan. Although, Cronenberg told Sight & Sound that he wanted the film to have an ambiguous time frame; not timeless, but not period-specific either. Note the absence of technology, television, and cars onscreen, setting the film in East London anywhere between the 1950s to 1980s, distinguished by its decrepit architecture, boarded-up windows, and skeletal gasworks tower. The period ambiguity echoes the overlap of past and present in Dennis’ mind. He experiences them in the same instant, remembering via onscreen flashbacks, while acting out those memories in the present, often in advance of the viewer experiencing them as Dennis relives them. While under the care of Mrs. Wilkinson (Lynn Redgrave) at the halfway house, Dennis attempts to remember what landed him there. He thinks back to his childhood, recalling his drunken and abusive father (Gabriel Byrne) and his seemingly angelic mother (Miranda Richardson), and gradually uncovers the events that led to his mother’s murder.

Spider is a rare Cronenberg film that shows interest in parent-child dynamics. Not since The Brood in 1979 had the director explored the trauma parents can inflict on their children, and Spider takes place around that same period—indicated by a café sign that says “Keep Britain Tidy,” a 1970s slogan. Although, Cronenberg told Sight & Sound that he wanted the film to have an ambiguous time frame; not timeless, but not period-specific either. Note the absence of technology, television, and cars onscreen, setting the film in East London anywhere between the 1950s to 1980s, distinguished by its decrepit architecture, boarded-up windows, and skeletal gasworks tower. The period ambiguity echoes the overlap of past and present in Dennis’ mind. He experiences them in the same instant, remembering via onscreen flashbacks, while acting out those memories in the present, often in advance of the viewer experiencing them as Dennis relives them. While under the care of Mrs. Wilkinson (Lynn Redgrave) at the halfway house, Dennis attempts to remember what landed him there. He thinks back to his childhood, recalling his drunken and abusive father (Gabriel Byrne) and his seemingly angelic mother (Miranda Richardson), and gradually uncovers the events that led to his mother’s murder.

Spider’s opening titles feature Rorschach-style imagery on weathered concrete, alluding to the story’s layers of old and interpretable memories. As ever, Cronenberg’s direction appears controlled and aesthetically realized in every detail, including the omnipresence of moldy wallpaper, frayed linoleum, and Fiennes’ disheveled appearance. It’s a testament to the actor’s desire to push his limits that, in the years after commercial successes such as Schindler’s List (1993), Quiz Show (1994), and The English Patient (1997), he chose to play Dennis Cleg (also in 2002, he appeared in The Good Thief, Maid in Manhattan, and Red Dragon). Regardless of his varied roles at the time, Fiennes disappears into Dennis, carrying himself under four layers of tattered shirts, tobacco-stained fingers, and a hunched posture. His slow, sometimes jerky movements, accented by his often inaudible and fragmented speech patterns, seem like the behaviors of an actual mental patient, not the actorly representation of one. The discordant notes of Howard Shore’s quiet score further accent Dennis’ mental state, just as cinematographer Peter Suschitzky and production designer Andrew Sanders convey the decrepit world Dennis inhabits, split between the external and internal, and shot with rotting hues that indicate the infected space in Dennis’ head.

Both as witness and participant, Dennis lumbers about, leaving the halfway house to retrace his steps from years earlier. He visits his childhood home and falls to the ground in the garden, at the spot where, we will learn later, his mother was buried. When a remembered moment achieves clarity in his mind, he logs the interaction in his journal, another clue to the mystery of his past. Elsewhere, he weaves literal webs using twine, hence the nickname. But the negative spaces in his webs indicate how his memories are surrounded by gaps. Together, the strings form an organization of ideas, albeit with holes of forgotten events and ill-remembered truths. Dennis’ fragmented mind is the prevailing symbol here, also visualized in a flashback to his time in the institution when a window breaks, and the cracks take the shape of a spider’s web. Dennis takes one of the shards, considers killing himself, then returns the piece to the head doctor. In scenes like this, Cronenberg depicts Dennis’ disturbed mindset in the character’s behavior and subjectivity, which alternates between past and present seamlessly. Sometimes Dennis’ memories overwhelm the present-day character, and sometimes they unfold in the back of his mind, depending on the intensity of the remembered event. Of course, this makes Dennis an unreliable narrator who confuses the person responsible for his mother’s death.

As Dennis’ memories become clarified, his situation provides a case study for Oedipal obsession. Freud contends that early childhood development inherently involves “falling in love with one parent and hating the other,” and these impulses occur in the unconscious mind. In Spider, Dennis harbors the feelings Freud describes, evidenced when his memories reveal his amorous impulses toward his mother and jealousy toward his father in his youth. Dennis’ feelings have continued into his conscious adult life and appear when he makes associations between his mother and his father’s mistress—the local “fat tart” Yvonne, played by Alison Egan in one scene. But when Dennis sees Yvonne interact with his father in his mind, the scene occurs at the local pub where the boy was not present, hinting at the trick his mind has played. Later, his mind replaces Yvonne’s face with his mother’s, and Yvonne is then played by Richardson. In the present, Dennis also projects his mother’s face onto Mrs. Wilkinson and a pornographic image of two topless pinup models. Indeed, Mrs. Cleg has become the dominant symbol of feminine authority, sexualized or not. Moreover, according to Freud’s theory, Dennis’ lust for his mother is a primitive wish he seeks to fulfill, which non-psychoneurotics will dismiss by adulthood. But Dennis’ neurosis is evident when he regularly sees women as his mother; therefore, Dennis still yearns for the same “wish-fulfillment” from childhood that Freud describes, and it has infected his memory with false associations.

As Dennis’ memories become clarified, his situation provides a case study for Oedipal obsession. Freud contends that early childhood development inherently involves “falling in love with one parent and hating the other,” and these impulses occur in the unconscious mind. In Spider, Dennis harbors the feelings Freud describes, evidenced when his memories reveal his amorous impulses toward his mother and jealousy toward his father in his youth. Dennis’ feelings have continued into his conscious adult life and appear when he makes associations between his mother and his father’s mistress—the local “fat tart” Yvonne, played by Alison Egan in one scene. But when Dennis sees Yvonne interact with his father in his mind, the scene occurs at the local pub where the boy was not present, hinting at the trick his mind has played. Later, his mind replaces Yvonne’s face with his mother’s, and Yvonne is then played by Richardson. In the present, Dennis also projects his mother’s face onto Mrs. Wilkinson and a pornographic image of two topless pinup models. Indeed, Mrs. Cleg has become the dominant symbol of feminine authority, sexualized or not. Moreover, according to Freud’s theory, Dennis’ lust for his mother is a primitive wish he seeks to fulfill, which non-psychoneurotics will dismiss by adulthood. But Dennis’ neurosis is evident when he regularly sees women as his mother; therefore, Dennis still yearns for the same “wish-fulfillment” from childhood that Freud describes, and it has infected his memory with false associations.

Similarly, Freud argues that conscious jealousy over the father’s sexual relationship with the mother is another sign of this neurosis. Sure enough, Dennis exhibits anger about his mother directing her affections toward his father, particularly when the boy stomps away after seeing his father groping his mother, or when his mother buys a new nightgown in an attempt to look sexy for his father. Freud suggests that a normal person would “live in ignorance” of these impulses; however, Dennis is attuned to his jealousy. His mind even fabricates tawdry scenes where his father, a plumber, visits Yvonne’s apartment like a scene out of a bad erotic fantasy (“You gonna do me pipes or what?” says Richardson’s Yvonne). Freud’s theory implies that Dennis’ awareness of his impulses propels him toward committing murder. He also notes that, when faced with the repressed or unconscious impulses of sexuality or jealousy toward their parents, a person will respond with feelings of guilt or even “self-punishment.” During childhood, Dennis does not show guilt about his conscious impulses. However, in adulthood, Dennis’ shame manifests, causing him to consider suicide. To be sure, Freud suggests “feelings of repulsion” are natural about these impulses, and Dennis acknowledges that these impulses are shameful, even if he cannot completely dismiss them.

In order to avoid future neuroses, Freud states that a child must set aside any sexual impulse toward his mother by also forgetting about the jealousy of his father. Freud argues that once people recognize their sexual impulses toward their mother and jealousy toward their father, people can “close our eyes to the scenes of our childhood.” But Dennis remains all too aware of his childhood impulses—they have shaped his life. He cannot close his eyes to his memories, which show that his father murdered his mother after she caught her husband with Yvonne, who then moves into their house to serve as a maternal replacement. So the young Dennis plans to kill his mother’s replacement, using his twine to create a line from the kitchen gas lever to his bedroom. When she returns from the pub, he pulls the twine and gasses her. Dennis acts out Freud’s assertion that the Oedipus Complex materializes in hatred for the father by murdering Yvonne to punish his father for killing his mother. And while Dennis has acted against what he believes is the third party, his memories gradually reveal that Yvonne never replaced his mother. His anger over his mother’s sexuality, directed at his father, created a new identity for her, transitioning her from the Madonna to the whore, a distinction so pronounced that she appeared to Dennis as another person: Yvonne. Upon realizing that he killed his own mother, Dennis recognizes his inability to disengage his Oedipal feelings in adulthood, not to mention the trauma of realizing he killed his own mother. At the end of the film, he returns to the mental institution from the halfway house.

The intellectual and psychoanalytic flavor of the film earned an enthusiastic response from some critics, but that did not translate to favorable box-office results. In an otherwise positive review, Roger Ebert complained, “The story has no entry or exit, and is cold, sad and hopeless”—not the makings of a crowd-pleaser. Made for a modest sum of $10 million, and one of the only films that Cronenberg shot outside of Canada, Spider earned back just over half of its budget. It would mark the second flop in a row for Cronenberg, after eXistenZ (1990), and remain ignored for much of his career. Still, at the Toronto Film Festival, Spider earned the prize for Best Canadian Feature, and it lingers as one of Cronenberg’s most underrated films, ushering in a new era of his work concerned with mental processes that have real-life consequences. In a way, that has always been Cronenberg’s interest, leaning into how sexual desire, repulsion, anger, and anxiety have horrible effects on the body. But Cronenberg’s work in the current century accompanies that theme with a concentration on the entangled spaces, compartmentalizations, and repressions in the mind outside of the horror genre. His more psychologically informed films continued with A History of Violence (2005), Eastern Promises (2007), A Dangerous Method, Cosmopolis (2011), and Maps to the Stars (2015).

The intellectual and psychoanalytic flavor of the film earned an enthusiastic response from some critics, but that did not translate to favorable box-office results. In an otherwise positive review, Roger Ebert complained, “The story has no entry or exit, and is cold, sad and hopeless”—not the makings of a crowd-pleaser. Made for a modest sum of $10 million, and one of the only films that Cronenberg shot outside of Canada, Spider earned back just over half of its budget. It would mark the second flop in a row for Cronenberg, after eXistenZ (1990), and remain ignored for much of his career. Still, at the Toronto Film Festival, Spider earned the prize for Best Canadian Feature, and it lingers as one of Cronenberg’s most underrated films, ushering in a new era of his work concerned with mental processes that have real-life consequences. In a way, that has always been Cronenberg’s interest, leaning into how sexual desire, repulsion, anger, and anxiety have horrible effects on the body. But Cronenberg’s work in the current century accompanies that theme with a concentration on the entangled spaces, compartmentalizations, and repressions in the mind outside of the horror genre. His more psychologically informed films continued with A History of Violence (2005), Eastern Promises (2007), A Dangerous Method, Cosmopolis (2011), and Maps to the Stars (2015).

Spider might also be one of the director’s most personal films. Cronenberg likened Dennis to an artistic archetype who creates “passionately and obsessively and with great attention to detail in a language that’s incomprehensible to anybody else and maybe even to himself.” The director links his romanticizing of interiority to Samuel Beckett’s novel Malloy, which he first mentioned at the Cannes Film Festival press conference after the film’s debut, and which shaped much of the critical discussion around the film at the time. But it also recalls Fyodor Dostoyevski’s Notes from Underground and the protagonist who declares, “I am writing this just for myself.” Dennis keeps his journal secret, hidden, jotting down his ideas in a format only readable to him. What is more, Spider’s astounding inwardness eschews any other character that would help Dennis resolve his mental preoccupations, leaving him to work through his neurosis and self-prescribe a solution. Cronenberg compared himself to Dennis in Sight & Sound: “I could see myself walking the streets muttering to myself and what I was saying would have meaning for me but for nobody else.” The director has always been independent, making films in a style and method all his own. Fortunately, Cronenberg continued making films well after Spider’s commercial failure, leaving audiences to consider how it launched a shift in his admirably independent films toward the raveled psychological characters that would come to define his twenty-first-century output.

(Note: This review was originally suggested on and posted to Patreon on February 24, 2022.)

Bibliography:

Beard, William. The Artist as Monster: The Cinema of David Cronenberg. University of Toronto Press, 2006.

Browning, Mark. David Cronenberg: Author or Filmmaker? Intellect, Ltd., 2007.

Freud, Sigmund. “The Interpretations of Dreams.” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. Ed. Vincent B. Leitch et al. W.W. Norton and Co., 2010, 807-824.

—. “Fetishism.” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. Ed. Vincent B. Leitch et al. W.W. Norton and Co., 2010, 841-845.

Jackson, Kevin. “Odd Man Out.” Sight & Sound, January 2003. http://old.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/feature/72. Accessed 18 February 2022.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review