Spencer

By Brian Eggert |

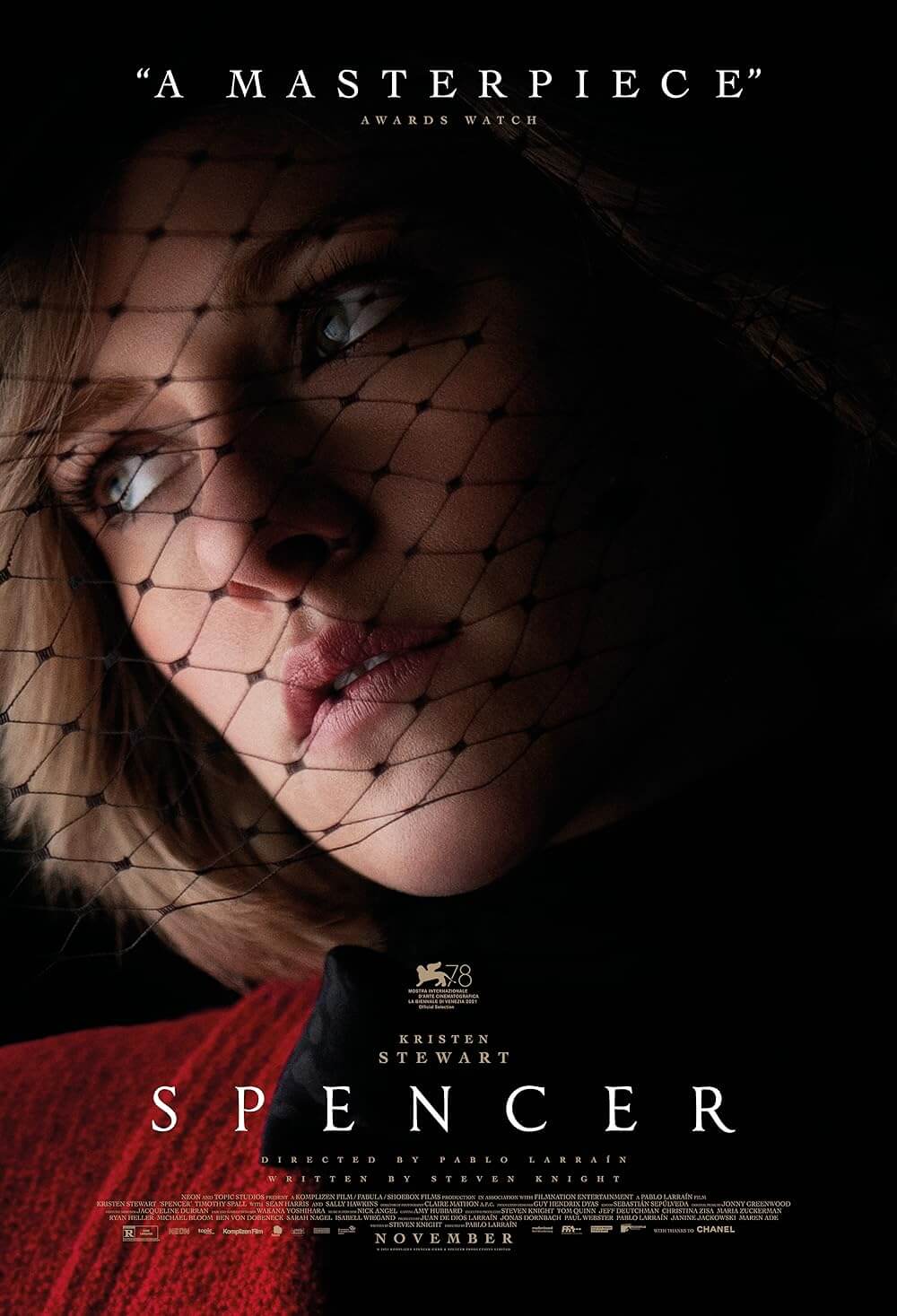

Spencer, Chilean director Pablo Larraín’s film about Princess Diana, avoids the traditional biopic structure and looks at a few days in the subject’s life. Titles explain the story as “a fable from a true tragedy,” which gives the proceedings a fatalistic quality not limited by documented history. The screenplay by Steven Knight begins on Christmas Eve and ends on Boxing Day, though the drama is neither festive nor jolly. Rather, the film captures the initial grim mood of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. The screen story unfolds around Sandringham House, a modest 600-acre estate in Norfolk (called a “country house” by the royal family). Inside, a whole contingent of veritable Scrooges demands adherence to tradition and balk at turning up the heat. The chilly old residence also contains ghosts—Diana’s taxed mind overflows with memories of a freer childhood and the looming presence of Anne Boleyn. Kristen Stewart stars as the late Princess of Wales, whose maiden name lends the film its title, giving a performance that isn’t so much an embodiment as a spirited interpretation. Like Scrooge in the Dickens story, Stewart’s Diana spends the film ruminating on her past, hindered by her present, and dreading the future. And given Diana’s fate, Spencer could hardly have the miraculous turn that Scrooge did, but the film offers something that could be called miracle-adjacent.

Perhaps Knight had the Dickens story in mind after penning a television miniseries adaptation of A Christmas Carol in 2019. Spencer isn’t a true Dickensian tale, of course, but it weighs similar themes of class and privilege against a Christmas backdrop. In one of the first scenes, we see a cavalcade of military vehicles deliver rectangular crates that look like they should contain missiles and machine guns. Then the house chef (Sean Harris) and staff emerge to open the containers, filled with an array of chilled produce and proteins, selected according to the royal family’s particular and extravagant taste. “Once more unto the breach,” declares Harris, who, quoting Henry V, treats meal preparation like a battle to the death. When Diana finally arrives late to the party—and worse, in her Porsche and unaccompanied by her security detail—she’s greeted by Major Alistair Gregory, played by Timothy Spall, an otherwise warm actor taken to cold-hearted roles in recent years (see Denial). Gregory, hawkish and always watching, has been enlisted by “the family” to keep Diana in line and out of trouble. He insists on a traditional “bit of fun,” where each member of the royal family must be weighed before and after the holiday—to measure the excesses. Diana refuses. But Gregory warns, “No one is above tradition.”

Therein lies the central pressure point in Spencer, a film about Diana’s outsider status among her so-called family. Diana, an international celebrity and iconic figure, died in 1997 in a car crash while avoiding the paparazzi. Before that, her presence in the tabloid media—fuelled in part by the not-so-secret affair that her husband Charles (played by Jack Farthing here) was having with his future wife—resulted in a fissure between herself and the royals. Knight, a screenwriter who often layers his scripts with heavy metaphors and symbolism, turns Diana into an unsubtle analogy to Anne Boleyn. Just as Henry VIII gave up Anne for Jane Seymour, Diana can sense Charles will eventually give her up for Camilla. But, of course, Henry didn’t merely carry on with an affair that was the worst kept secret in court; he accused Anne of infidelity and had her executed. Accordingly, Diana’s not-unfounded feelings of paranoia are furthered by her bulimia, hints at self-mutilation, and apparent persecution—evidenced by the Anne Boleyn biography that someone in the house has placed strategically on Diana’s bed. Before long, Diana begins to see Anne and talk to her in hallucinatory moments.

Who better to play Diana, someone fraught with insecurity, than Stewart, who has specialized in roles filled with anxiety and inner torment? If she doesn’t disappear into the role, Stewart’s more diminutive stature (by five inches) nonetheless reflects Diana’s mental state—shrunken by constraint from the royals, her failing marriage, and the ever-hounding press. However, the performance captures Diana’s breathy voice, her tendency to look up from a downturned head, and the way she looks at the world from a tilted angle. Yet, Spencer actively resists realism in favor of capturing Diana’s rebellious spirit and yearning for authenticity. For instance, Stewart maintains a grounded and somewhat anti-establishment public image, and that quality bleeds over into the performance. Similarly, her Diana has a line about being “quite middle-class” in her love of fast-food and Andrew Lloyd Webber musicals. Given her aristocratic airs and advantages, the line is an anachronism, to be sure. But it frames Diana as someone who doesn’t fully conform to the tastes and superior sense of self that her fellow royals do.

Who better to play Diana, someone fraught with insecurity, than Stewart, who has specialized in roles filled with anxiety and inner torment? If she doesn’t disappear into the role, Stewart’s more diminutive stature (by five inches) nonetheless reflects Diana’s mental state—shrunken by constraint from the royals, her failing marriage, and the ever-hounding press. However, the performance captures Diana’s breathy voice, her tendency to look up from a downturned head, and the way she looks at the world from a tilted angle. Yet, Spencer actively resists realism in favor of capturing Diana’s rebellious spirit and yearning for authenticity. For instance, Stewart maintains a grounded and somewhat anti-establishment public image, and that quality bleeds over into the performance. Similarly, her Diana has a line about being “quite middle-class” in her love of fast-food and Andrew Lloyd Webber musicals. Given her aristocratic airs and advantages, the line is an anachronism, to be sure. But it frames Diana as someone who doesn’t fully conform to the tastes and superior sense of self that her fellow royals do.

Spencer doesn’t play by their rules, either. Following his superb work on 2016’s Jackie, Larraín, ever the iconoclast, delivers another of his artful anti-biopics. But where his Jacqueline Kennedy film offered a framing device and fleshed-out flashbacks to break the narrative’s immediate present, his Diana film remains entrenched in the present, except for a few momentary glimpses of Diana’s youth. Even so, Diana’s headspace occupies much of the film, and Larraín’s form follows suit. Claire Mathon’s saturated cinematography feels like a hazy relic of the past; however, the images place us inside Diana’s subjectivity thanks to handheld cameras with wide-angle lenses that follow her around the estate. Elsewhere, Larraín frames the house with Kubrickian symmetry and long shots down corridors and hallways that recall The Shining (1980)—a film he, consciously or not, evokes more than once. Watch the moment in the bathroom where Diana thinks she’s embracing one attendant but, horrifically, it turns out to be another, and try not to think of Jack Nicholson hugging a naked woman who transforms into a decrepit corpse in his arms.

If the film’s “fable” emerges in how Dickens and Anne Boleyn haunt Diana, the “tragedy” remains offscreen. Set in the early 1990s, the film sets the stage for Diana’s last few years and, in the end, finds her somewhat accepting of her antagonistic relationship with the royals. Larraín positions Diana as someone who just wants to be free, drive around, and eat the occasional bucket of Kentucky Fried Chicken with her boys, Willian (Jack Nielen) and Harry (Freddie Spry). Only with them does she let her guard down and seem genuinely happy, leading to a lovely scene of play involving military voices and revealing questions. Alternatively, she buckles against the heightened security, rigid schedules, and wardrobe changes the family demands during their dull Christmas routine. Seeing her crack under pressure, William tells her to “Switch off your mind,” while her trusted royal dresser Maggie (Sally Hawkins) tells her to “Fight them—be beautiful.” For Diana, being herself might be the only way to combat a family that believes “All you are is currency.” It’s an idea that once more recalled Dickens, especially when Johnny Greenwood’s exceptional score of dissonant notes and jazzy inflections includes subtle metallic sounds that reminded me of Marley’s chains—an aural symbol of Diana’s imprisonment.

Spencer never feels like another stodgy production designed to glorify the monarchy. Although shows like Netflix’s The Crown tend to romanticize the UK’s heads of state for all their splendor and pageantry, Spencer feels like a sharp takedown of the royal class—made by an arthouse director, a writer well-versed in exposing England’s underbelly, and a performer who has actively stepped away from mainstream Hollywood. Diana has recently been played by Naomi Watts and will soon be portrayed by Elizabeth Debicki, but there’s an edge to Stewart that makes Diana feel real. We perceive the forces working against her, sometimes indirectly—such as when she sneaks away to visit her boarded-up childhood home, where, in a twisted turn, Gregory seems to hope she will meet her demise. Because Spencer makes Diana come to life, every second she spends among the royals and their absurd ranks proves intolerable and grating. And their grotesque establishment of order and tradition makes Diana all the more appealing in her rebelliousness, from her palette of pastel blues, pinks, and yellows, to the deliriously enjoyable dancing and running montages that show Diana at her most unbridled. The film, like its subject, feels impulsive and impressionistic, and those peculiarities and deviations from the norm should be cherished—they couldn’t be more appropriate.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review