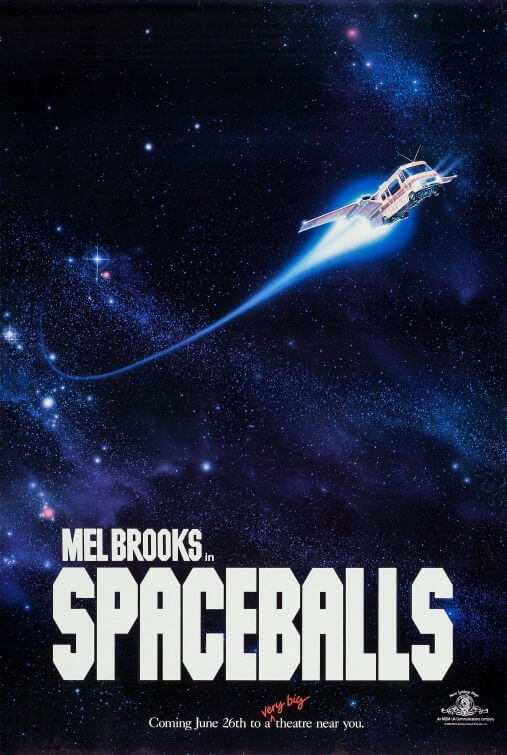

Spaceballs

By Brian Eggert |

By 1987, the Star Wars phenomenon had run its course. George Lucas’ original trilogy had been over for three years. Fans of the series were left under their mounds of Kenner action figures and movie memorabilia. Two made-for-TV movies, Caravan of Courage: An Ewok Adventure and Ewoks: The Battle for Endor in 1984 and 1985, sustained fandom a little longer, albeit badly. More toys and videogames, along with theatrical re-releases helped fan the flame too. Ten years after Lucas’ original Star Wars, Mel Brooks released his spoof Spaceballs, which was critically panned and modestly profitable in its theatrical run. In subsequent years, however, the film has become a cult hit thanks to recurrent appearances on cable television and numerous editions on various home video formats. Returning to the film today, there’re an admirable charm and nostalgia involved in screening Spaceballs, even if the jokes are rarely laugh-out-loud funny and more just silly fun.

Though he had been directing original feature-length comedies since The Producers (1968) and The Twelve Chairs (1970), Brooks’ films since Blazing Saddles in 1974 had been parodies and homages of genres and particular films from Hollywood’s Golden Age. He spoofed Universal Studios monster fare with Young Frankenstein, also in 1974. He nodded to Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton with Silent Movie in 1975; he even convinced famous mime Marcel Marceau to speak the film’s only line of dialogue. And the next year, he used a compendium of Alfred Hitchcock tropes in High Anxiety, which Hitchcock actually saw and complimented. Each film boasts an impressive formal style that perfectly mimics its target. For example, Young Frankenstein looks as if it was shot in the 1930s, using black & white photography and special FX, cheapie sets, and lighting tricks of the era. Brooks recreated the look and feel of 1950s Westerns with Blazing Saddles, complete with naïve racism and sun-bleached photography. And so on.

By the time the mid-1980s rolled around, Star Wars fatigue may have settled into critics, but its cultural influence was still very potent. Other satirists had poked fun at Star Wars in various ways, but no one had the guts to produce a barefaced spoof of Lucas’ franchise with direct references. Though it was a ballsy move on Brooks’ part, it seemed to come far too long after-the-fact; to be sure, it’s surprising no one had done this before. Before he set out make the film, he sought Lucas’ blessing. Lucas’ only stipulation was that Brooks couldn’t sell Spaceballs merchandising because the toys would look too much like those for Star Wars; and yet, the absurdity of the merchandise depicted in the film (Spaceballs dolls, bedsheets, toilet paper, flamethrower, etc.) is one of the best jokes. Playing to Lucas’ pride, Brooks also requested that post-production effect be completed at Skywalker Ranch for an authentic look. Lucas, ever willing to participate in self-abasement (see the Family Guy and Robot Chicken spoofs of Star Wars, which Lucas officially approved), agreed. Even if the story of Spaceballs was a spoof, the production would look top-notch.

Our hero, an amalgam of Han Solo and Luke Skywalker, is Lone Starr, played by then-unknown Bill Pullman. Alongside his furry pal Barf (John Candy), a half-man, half-dog creature called a “Mawg”, Lone Starr owes a debt to gangster Pizza the Hutt (Dom DeLouise inside a disgusting, drippy costume). Fortunately, Princess Vespa (Daphne Zuniga) of planet Druidia has just fled her marriage to the sleepy Prince Valium (Jim J. Bullock), and her father (Dick Van Patten) offers a reward to Lone Starr if he can bring her back. Meanwhile, the leader of the evil planet Spaceball, President Skroob (Brooks, who insists “Skroob” is “Brooks” spelled backward, even though it isn’t), plots to steal Druidia’s air with the help of his minions, Dark Helmet (Rick Moranis) and Colonel Sandurz (George Wyner, named after the KFC icon). After securing the Princess and running from the Spaceballs, Lone Starr eventually learns from the wise, gold-skinned Yogurt (also Brooks), that he has a destiny to become a master of the “Schwartz” (as in “May the Schwartz be with you”). By the end, Lone Starr saves the Princess (again), stops the Spaceballs’ evil plot using the Schwartz, and becomes a Prince to marry the Princess.

Several self-referential and Fourth Wall-breaking remarks keep the film a very meta experience, before such humor was virtually the basis of modern comedy. This quality also distances us from the plot. From the very first scene where the scrolling titles remark “If you can read this, you don’t need glasses,” we’re more concerned with the gags than the story. In between hilarious sequences like the VHS-within-a-film viewing of Spaceballs during Spaceballs, lesser jokes wink at the audience. Among the best is the scene where Yogurt remarks “Merchandising, merchandising, merchandising!” and takes a shot at Fox and Lucas. Still, the humor is mostly grounded in silliness. Whereas Brooks’ earlier films winked less at the audience, Spaceballs seems determined to over-emphasize its jokes. Rarely is subtlety involved. This was the beginning of a period of lesser spoofs for Brooks, all very broad and quite lazily assembled. Brooks’ Robin Hood: Men in Tights (1993) and Dracula: Dead and Loving It (1995) responded to the popularity of Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991) and Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) respectively, but they had more in common with their older counterparts, The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) and Tod Browning’s Dracula (1931).

Regardless of Spaceballs’ box-office success ($38 million earned on a $25 million budget), critics met the film with a lukewarm response. Roger Ebert said it best when he descended into the quandary of assessing a film like Spaceballs within his review: “I dunno. How do you review a movie like this, anyway? I guess by saying whether you laughed or not. I did laugh, but not enough to recommend the film.” Ebert makes an excellent point, because although Spaceballs does make me laugh, I spend a lot of time rolling my eyes and thinking how obvious this or that joke was. There’s not much wit involved in Spaceball One transforming into Mega Maid, whose two settings are “suck” and “blow”. There’s nothing clever about his version of Jawas, played by dwarves in robes, saying nothing but “dink” (slang for “dinky” or “penis”). Along with a bland soundtrack comprised of dated eighties tunes from the likes of Van Halen, The Pointer Sisters, Berlin, and most offensively The Spinners’ “Spaceballs” song, there’s a cheesy quality to the film that’s less charming than embarrassing.

Elsewhere, laughs aplenty come from Moranis and Candy, the film’s true standouts, especially next to the comic inabilities of Pullman and Zuniga. Moranis remains a hilarious addition, his small stature and large helmet (another penis joke) resulting in physical humor galore, including several references to his sense of inadequacy. Candy couldn’t be more charming, especially when he takes on more dog-like inflections; his wagging tail and perked ears manage to be cute and funny at the same time. Pullman and Zuniga fill archetypal hero and princess roles, with most of their jokes being written around them rather than through them. For example, Vespa’s superficiality (her hair dryer, nose job, and general prissiness) define her. Rivers hardly engages in her signature edgy humor of the period; she’s present seemingly to drop her standup catchphrase, “Can we talk?” Still, there are several guilt-free laughs throughout, many of them resulting from references to material other than Star Wars, such as The Planet of the Apes, Star Trek, Max Headroom, and curiously Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis (the most highbrow moment in the film).

The best of the references must be a late scene where Lone Starr and Barf stop at a greasy spoon in space. While there, a group looking suspiciously like the crew from Alien, and one of them actually played by that film’s star John Hurt, reenact the scene where the alien bursts from Hurt’s chest. The creature screams and leaps onto the countertop. Hurt resigns, “Oh no, not again.” The alien proceeds to sing “Hello, My Ragtime Gal” in the style of Merrie Melodies cartoon character Michigan J. Frog, complete with top hat and cane, and leaps through a small door on the other end of the counter. “Check please!” declare our heroes. It’s a random reference, using a song from 1899, a cartoon from 1955, and a film from 1979. But that’s how Brooks operates. In many ways, he’s making these films not for a Star Wars audience but for himself, driven by what makes him laugh, and by what has continued to make him laugh since before he started working for Sid Caesar in the 1950s. But the popularity of all things related to Star Wars would cancel out any valid criticisms of the film and make Spaceballs Brooks’ most popular release, yet far from his best.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review