Reader's Choice

South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut

By Brian Eggert |

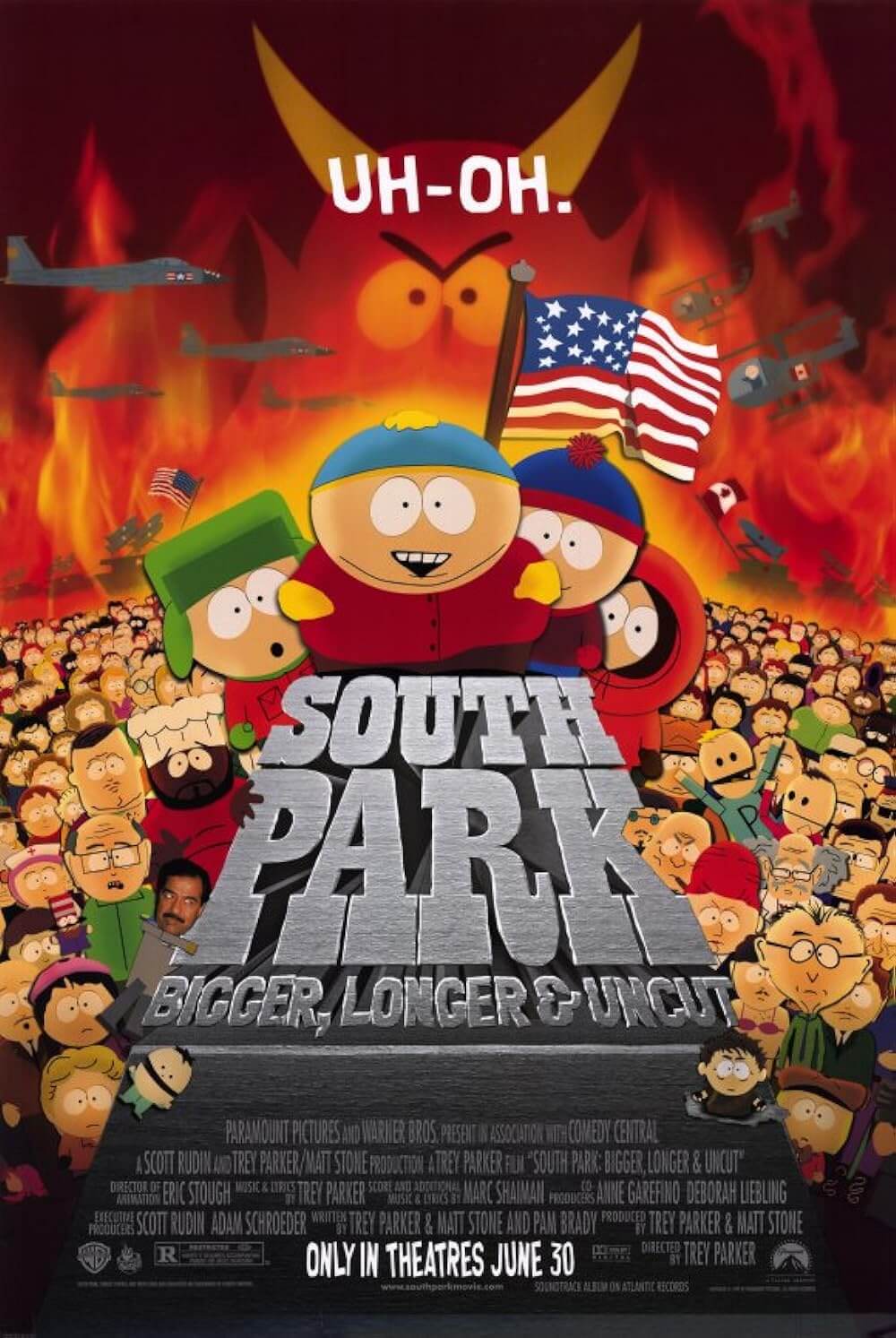

Some movie theater experiences you never forget. It was the summer of 1999, and I had just received my driver’s license and started to explore my newfound freedom on the road. Soon I would get my first job, hawking overpriced VHS tapes and DVDs at Suncoast at the mall. In a few months, I would enter my senior year of high school. But for now, my summer would be spent at the movies with American Pie, Eyes Wide Shut, Run Lola Run, The Sixth Sense, The Thomas Crown Affair, and The Muse. The list goes on and on. It was an unforgettable year for film, widely regarded as one of the greatest ever. And so, on a sleepy Friday morning, I settled into my new ritual of seeing movies by myself on opening day, usually at the earliest matinee. That day in late June, I would see South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut. A few other teenagers and some rough-looking middle-aged men entered the theater, but mostly the audience was comprised of parents with their young children. Did they not know about South Park? Had they not seen the MPAA rating?

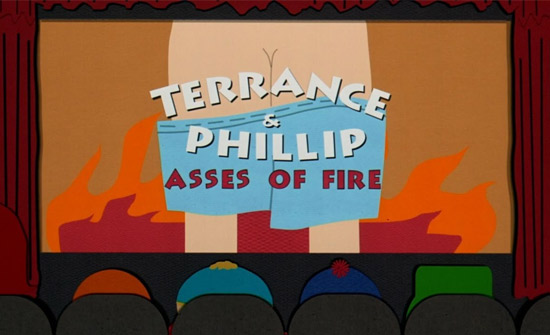

The movie started. An establishing song called “Mountain Town” proved only mildly offensive. I thought to myself, When will these parents realize they’re in the wrong movie? They had children who looked under 10-years-old. Surely they wouldn’t expose their kids to the movie for much longer. Then, on the screen, Stan, Kyle, Cartman, and Kenny paid a drunk to see the hotly anticipated Terrence and Phillip movie, a foreign film from Canada called Asses of Fire. Some parents started to scurry out with their children once the word “asses” made an appearance. Then Terrence and Phillip sang the song “Uncle Fucka,” and more parents rushed their children out of the auditorium. Even so, other parents stayed. And I think it was about an hour later, around the time that Saddam Hussein pulled out a realistic-looking dildo to taunt his gay lover Satan, that I realized, no matter what, some of these parents just don’t care what their children see. After all, the title is a dick joke. More than half of the families stayed for the entire 81-minute runtime. It was the first time I noticed how irresponsible parents could be about movies.

Then again, much like the boys in the “quiet little white-bred redneck mountain town” and their desperate need to see Asses of Fire, I wasn’t going to miss this swear-fest. Ever since Trey Parker and Matt Stone’s animated show debuted on Comedy Central two years earlier, teens had absorbed the boundary-pushing language and repeated it (usually in a bad Cartman voice) in school hallways and lunchrooms. The filmmakers knew about the phenomenon and had anticipated the reaction to their movie. Their story follows the children of South Park using Asses of Fire’s foul language at recess and in classrooms, prompting Kyle’s helicopter mom Sheila to launch a boycott of Terrence and Phillip, ultimately leading to a war between the US and Canada. Parents had rallied against the South Park show in real life before. But the movie would only be a sidebar in the omnipresent discussion saturating the zeitgeist in 1999—a debate about whether popular culture was warping the “fragile little minds” of America’s youth.

Then again, much like the boys in the “quiet little white-bred redneck mountain town” and their desperate need to see Asses of Fire, I wasn’t going to miss this swear-fest. Ever since Trey Parker and Matt Stone’s animated show debuted on Comedy Central two years earlier, teens had absorbed the boundary-pushing language and repeated it (usually in a bad Cartman voice) in school hallways and lunchrooms. The filmmakers knew about the phenomenon and had anticipated the reaction to their movie. Their story follows the children of South Park using Asses of Fire’s foul language at recess and in classrooms, prompting Kyle’s helicopter mom Sheila to launch a boycott of Terrence and Phillip, ultimately leading to a war between the US and Canada. Parents had rallied against the South Park show in real life before. But the movie would only be a sidebar in the omnipresent discussion saturating the zeitgeist in 1999—a debate about whether popular culture was warping the “fragile little minds” of America’s youth.

Two months earlier on April 20, high-schoolers Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold walked into Columbine High School armed with automatic weapons, killing 12 students and a teacher before turning the guns on themselves. Politicians and the media attributed the killers’ behavior to violent video games; music by Marilyn Manson; internet chat rooms; and movies such as The Matrix (1999), The Basketball Diaries (1995), and Natural Born Killers (1994). Pundits blamed everything but the two teens who needed psychiatric help and had disturbingly easy access to firearms. Columbine marked the boiling point of a long discussion about US censorship in the 1990s. In the years before the South Park movie, the Clinton administration showed support of V-chip technology that would allow parents to restrict their children from seeing television content with adult language, violence, and sex—all with a simple device installed in the TV set. Parents groups and PTA boards now had a systemic method to protect America’s child-viewers. Still, children found ways to watch South Park episodes with titles like “An Elephant Makes Love to a Pig” and “Cartman’s Mom Is a Dirty Slut” anyway. You could just record the episodes on a VHS tape and share it with friends.

What’s so fascinating about South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut is the same thing that makes the show an enduring source of timely commentary on, and an affront to, American taboos. Parker and Stone write and animate their episodes, sometimes within the span of a week, ensuring the relevancy of their perspective—their movie even features a reference to Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace, which opened six weeks earlier. But they’re also great prognosticators. They wrote their screenplay well before Columbine, aiming their self-aware satire at the predictable reaction to their movie. They understood how their predominantly under-18 audience would respond, and their movie preemptively lampooned the response. After the boys take to the playground to display their newly colored vocabulary, Sheila puts her foot down. Cartman becomes the guinea pig for Sheila’s dastardly plan to curb children from using foul language. In a setup recalling A Clockwork Orange (1971), the powers that be install a V-chip in Cartman’s brain, giving him a nasty shock whenever he utters affronts such as “shit-faced cockmasters” or even “piss.” But Sheila’s decidedly American brand of hypocrisy rationalizes that “naughty words” should be cut from Asses of Fire, but she has no problem with graphic violence. It’s a story beat that would anticipate the outrage to follow the release of Parker and Stone’s movie.

Despite the film’s mostly positive reviews and respectable summer box-office take, South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut became a target among censorship advocates. Jack Valenti said it should’ve been rated NC-17, the death knell for any theatrical release. Some critics showed their moralist streak, including Roger Ebert. “Not since Andrew Dice Clay passed into obscurity have sentences been constructed so completely out of the unspeakable,” wrote Ebert, who rated the movie two-and-a-half stars and admitted to feeling “offended.” If the film earned a more lenient R rating because it was a cartoon, as many commentators suggested, people began to raise questions about whether ratings could be trusted. The next year, Valenti’s MPAA resolved to expand their rating to include descriptions for concerned parents—as if “under 17 requires accompanying parent or adult guardian” were somehow ambiguous. Based on what I saw in the theater on opening day, parents both ignored the rating and, once Terrence calls Phillip a “donkey raping shit eater” in the first five minutes, didn’t have the good sense to escort their children to Disney’s Tarzan in the next auditorium.

Despite the film’s mostly positive reviews and respectable summer box-office take, South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut became a target among censorship advocates. Jack Valenti said it should’ve been rated NC-17, the death knell for any theatrical release. Some critics showed their moralist streak, including Roger Ebert. “Not since Andrew Dice Clay passed into obscurity have sentences been constructed so completely out of the unspeakable,” wrote Ebert, who rated the movie two-and-a-half stars and admitted to feeling “offended.” If the film earned a more lenient R rating because it was a cartoon, as many commentators suggested, people began to raise questions about whether ratings could be trusted. The next year, Valenti’s MPAA resolved to expand their rating to include descriptions for concerned parents—as if “under 17 requires accompanying parent or adult guardian” were somehow ambiguous. Based on what I saw in the theater on opening day, parents both ignored the rating and, once Terrence calls Phillip a “donkey raping shit eater” in the first five minutes, didn’t have the good sense to escort their children to Disney’s Tarzan in the next auditorium.

What made the film so impactful for me at the time wasn’t that Parker and Stone had captured the spirit of the censorship debate, which, admittedly, I was mostly oblivious to around that time. Rather, it was that they had made musicals accessible for teenagers who were hungry for gross-out humor, more dick jokes, and yet-unimagined combinations of swear words delivered at a rapid-fire pace (even today, it’s difficult to keep up with the jokes without laughing through them). Taking the shape of a classic movie musical, South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut features clever lyrics and catchy melodies. The songs “I Can Change” and the Oscar-nominated “Blame Canada” stand alongside new versions of the TV show favorites, such as “Kyle’s Mom’s a Bitch.” It takes elements of Disney animated films, from the conventional “I Want” song to the usual ambitious villain number found in The Little Mermaid (1989) and The Lion King (1994), and imbues them with outrageous lyrics. When so many movie musicals today fail to earn a place in the memory banks, this one is composed of almost entirely unforgettable songs from start to finish.

Rendered on computers to create the illusion of cutout animation, the film looks like living construction paper, making the result seem like the work of demented children—a technique Parker and Stone used to create their earliest versions of South Park. The show (now in its twenties) has since become somewhat more sophisticated looking, whereas the movie’s scenes set in Hell, created with outdated computer effects, haven’t aged well. Some of the humor, too, has since become, shall we say, troublesome. It’s doubtful South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut would be released in theaters today. The movie would probably get no further than Paramount+, where it would be dispersed into the ether of streaming content and less likely to offend the masses. The filmmakers target the media, politicians, the warmongering military, institutional racism, and American exceptionalism (the list doesn’t end there), and often in the most shocking ways imaginable, evidenced in its use of racial and homophobic stereotypes. Parker and Stone know they’re going to make people angry; part of their agenda is to draw attention by giving everyone something to laugh at or feel sensitive about.

The movie’s offend-everyone stance is at once refreshing and, ultimately, an armor for its own downfalls. The sociopolitical nihilism of Parker and Stone mocks anything and everything, often picking targets from the loudest voices. Defending their outpouring as jokes, so lighten up, Parker and Stone play into a vicious circle that Spike Lee investigated a year later with Bamboozled (2000)—a film that sees the value of satire, yet it warns that the message can be misinterpreted, regardless of intent. Representations of a negative idea, even if intended as a joke, can be harmful, because once the image or nasty remark is out there, the intended context doesn’t matter. It’s the audience’s now, to use in whatever ugly way they see fit. And while it’s easy to dismiss those who don’t get the jokes as idiots, it’s more difficult to ignore the movie’s homophobic or anti-Semitic remarks in a time when such sentiments have increased in America. When you’re seventeen and the world still seems like a sane place, these jokes feel gleefully anti-everything. When you’re coming up on 40 and you see these ideas materializing more and more, it’s harder to conjure laughter for them.

The movie’s offend-everyone stance is at once refreshing and, ultimately, an armor for its own downfalls. The sociopolitical nihilism of Parker and Stone mocks anything and everything, often picking targets from the loudest voices. Defending their outpouring as jokes, so lighten up, Parker and Stone play into a vicious circle that Spike Lee investigated a year later with Bamboozled (2000)—a film that sees the value of satire, yet it warns that the message can be misinterpreted, regardless of intent. Representations of a negative idea, even if intended as a joke, can be harmful, because once the image or nasty remark is out there, the intended context doesn’t matter. It’s the audience’s now, to use in whatever ugly way they see fit. And while it’s easy to dismiss those who don’t get the jokes as idiots, it’s more difficult to ignore the movie’s homophobic or anti-Semitic remarks in a time when such sentiments have increased in America. When you’re seventeen and the world still seems like a sane place, these jokes feel gleefully anti-everything. When you’re coming up on 40 and you see these ideas materializing more and more, it’s harder to conjure laughter for them.

As I’ve gotten older, both the South Park show and this movie have continued to remain cutting edge, despite missteps and some occasional self-atonement by Parker and Stone. Every election year, I laugh when they characterize the voter’s choice between a “giant douche” and a “turd sandwich.” Some things never change. Likewise, the movie’s funniest humor is timeless. Take the running gag about Stan asking Chef what it takes to make a woman happy. In his customarily inappropriate way, Chef replies, “That’s easy, you just gotta find the clitoris.” Stan’s journey leads him to the mythical clitoris: a floating wad of flesh with the voice of Glinda the Good Witch. The story, while culled from a preoccupation in the ‘90s with censorship, is still germane. Its defiant attitude, relentless laughs, and soundtrack of well-composed songs still manage to make the 81-minute runtime feel breezy. But the movie remains significant for me as one of a number of moviegoing experiences forever chiseled into my mind from the summer of 1999. For a foul-mouthed cartoon based on a Comedy Central show, it managed to draw connections between musicals, politics, censorship, cinematic ideology, and base humor in ways that I could not have expected and will never forget.

(Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thanks for your continued support, Dustin!)

Powered by

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review