Source Code

By Brian Eggert |

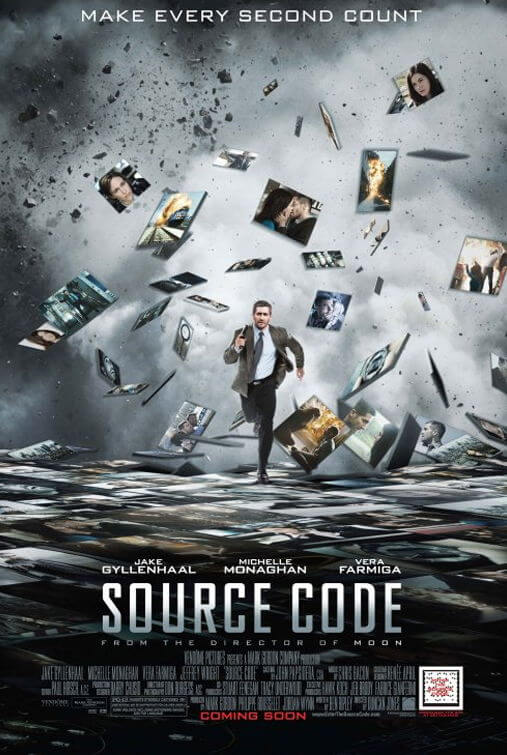

For a science-fiction thriller, Source Code delivers enough suspense to appease general audiences but lacks even coherent hypothetical science that will invite heady discussions of multiverse logic and quantum physics among those concerned about such things. (Incidentally, this review discusses such faulty logic in minor detail; those who want to be completely unspoiled have been warned.) This is, in a way, a disappointing second release from director Duncan Jones, whose Moon proved such a breakout hit among genre fans, even if the low-budget release failed to reach a larger market. In one respect, Jones’ new film forgoes plausibility to appease mainstream audience expectations; in another respect, he makes a smart career move by proving he’s capable of catering to commercial sensibilities and delivers a sharply directed thriller that will probably perform well at the box-office.

Jake Gyllenhaal stars as Captain Colter Stevens, a pilot who believes he should be flying missions in Afghanistan. Instead, he wakes up on a commuter train bound for Chicago, and the woman across from him, Christina (Michelle Monaghan), keeps calling him Sean. Disoriented, Stevens tries to make sense of what’s happening to him, and that’s when the train blows up. When Stevens comes to, he awakens in a capsule of some kind, where he’s debriefed via video screen by Goodwin (Vera Farmiga), who refuses to explain beyond the basics: Stevens is set to inhabit the body of Sean, one among hundreds of victims of a terrorist train bombing earlier that day. Stevens has the last eight minutes of Sean’s brainwaves to explore before he was killed to look for clues. If within this convoluted alternate reality known as “source code” Stevens can find out who bombed the train, then Goodwin and the program’s inventor, Dr. Rutledge (Jeffrey Wright), can help authorities stop the bomber from taking out another target. You would think this means Stevens only has access to Sean’s experiences within the 8-minute timeframe, but you’d be wrong. The “source code” curiously gives Stevens access to an entire world regardless if Sean was there or not.

At first, Ben Ripley’s screenplay unfolds like the lovechild of Groundhog Day and The Matrix. Stevens returns to his 8-minute window, again and again, noticing little differences each time. He slowly falls for Christina, and, in time, tries to stop the bomb within the “source code” rather than gather the intelligence needed to stop another bombing in the “real world”. Of course, Stevens questions the concept of what is real with Goodwin, but since we’re told the “source code” exists within the last eight minutes of Sean’s memory, and that ostensibly the whole movie is an advanced simulation, the audience never believes Stevens will “make it”. To that effect, there’s a moment in the finale where the film pauses, and had it ended there, it would’ve been a satisfying-if-tragic conclusion. However, the “happy ending” coda that immediately follows the pause stretches already loosely assembled logic beyond its breaking point and proves itself downright silly.

Jones maintains a fast-paced momentum with enough energy and talent onscreen for the audience to overlook any plot holes until that nonsensical ending arrives, or even until post-screening discussions. Gyllenhaal’s strong hero presence grabs our attention and propels the entire film, while Farmiga and Monaghan give generous personality to their peripheral roles. In many ways, Source Code and Moon share much in common: Both feature themes of repetition, a lone protagonist confined to a limited space, and crucial questions of identity. But where Jones’ debut used the nuanced performance(s) of Sam Rockwell as its main set piece, this film employs a conventional, actionized scenario about a bomb on a train and a ticking countdown. Not that the result isn’t entertaining, but unfortunately it’s not as smart as it wants to be, or could have been.

Yet, who can blame Jones for signing on to such material? He’s confirmed that he wants to make loftier science-fiction projects in the future. And so, with this calculated project he takes on mid-level material to confirm to Hollywood that he’s competent enough to generate a profitable film. It’s a deliberate career move in the right direction, but it’s also disappointing that he didn’t preserve the same level of artistic credibility displayed in Moon. And though this review may seem preoccupied with Source Code’s story and not enough with Jones’ slick direction and the involving first two-thirds, the viewer will have to ask themselves what matters more: the thrills throughout or the payoff in the end? Perhaps it’s too much to ask for a balance between presentation and story. Moviegoers out for pure entertainment value will enjoy the result, but those who struggle with defective story logic may have trouble leaping the vast distances required to scale the film’s plot holes.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review