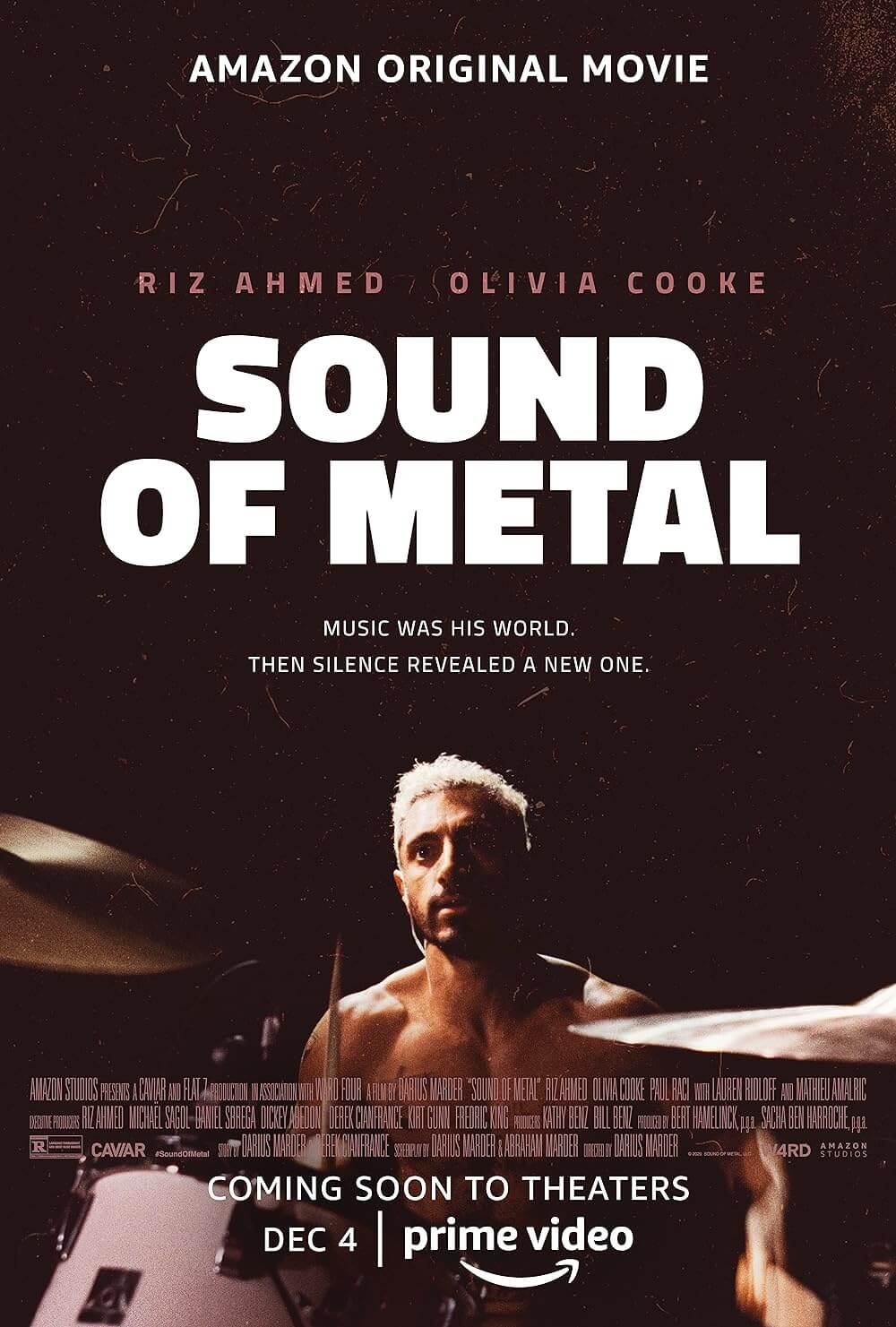

Sound of Metal

By Brian Eggert |

Using noise as a powerful metaphor for addiction, Sound of Metal offers an immersive human drama propelled by a superb central performance. Riz Ahmed plays Ruben, the drummer in a punk-metal duo, first seen bashing away at his skins during a live concert. Nearby, his partner Lou (Olivia Cooke) howls into a microphone and thrashes her guitar. His bare chest and arms covered in tattoos, his hair bleached white, Ruben beats the drums with a purpose. The decibel level drowns out any desire to keep using, and it has kept him clean for four years, living on the road and touring alongside Lou. When suddenly his hearing declines and brings him to the brink of deafness, Ruben teeters on the edge of sobriety. The directorial debut of Darius Marder, whose only feature credit is for co-writing Derek Cianfrance’s The Place Beyond the Pines (2012), the film offers inclusive storytelling about raw, distressed characters, while it also makes viewers aware of a deaf community that doesn’t necessarily believe there’s something wrong that needs to be fixed. Wherever one might fall on the issues it presents, Sound of Metal is a stirring character study about finding inner peace.

Desperate to correct his condition, Ruben learns that his so-called solution might be cochlear implants, which cost thousands more than he has. Lou, meanwhile, scrambles to find a place where Ruben might find some clarity. They both behave as though, without his musical outlet, Ruben is a time bomb, ticking away until the moment he returns to his drug of choice: heroin. Fortunately, they locate a deaf community secluded in the country and operated by Joe (Paul Raci), a recovering alcoholic who lost his hearing in Vietnam. Joe, who has seen people like Ruben before, gives him access to learning paths that teach him sign language and provide living conditions designed to help him confront his addiction. But staying under Joe’s roof also means isolation, requiring Lou to leave and stay with her father (Mathieu Almaric). The story becomes one of Ruben rallying against his new deafness, unwilling to accept what he sees as a limitation and the deaf community does not. At the same time, he’s meant to be identifying the self-destructive elements in his life, whether it’s his past drug use or addiction to touring with Lou.

Under the surface, Marder’s screenplay, co-written by his brother Abraham from an idea conceived in part by Cianfrance, Sound of Metal addresses the distinction between deafness as a state of being or a problem to be corrected with therapy or surgery. Joe’s community believes the former—that they can exist in a world of sign language and shared experience. Ruben’s time among them feels like he’s a tiger behind bars, pacing and unable to settle. He calms himself enough to teach a class or play with children at a local school for the deaf, but back at Joe’s shelter, he’s unable to write or “just sit,” as Joe instructs. Instead, Ruben smashes his breakfast and screams into the silence. But Joe understands that his community of former addicts needs inner peace more than an aural sense. From these scenes of Ruben alone, it becomes evident that Marder’s film is, arguably, less an eye-opening drama about the deaf community than a story about addiction. Ruben remains afflicted by a constant mental agitation that leaves him unable to slip into a state of stillness and quiet. Whether he numbs that agitation with heroin or drowns it out with punk-metal, it lingers in his mind.

Then again, Marder’s most daring conceit remains the subtitles that, depending on where you watch Sound of Metal, will appear onscreen. When seen theatrically or at festivals, the film came with subtitles that captured what Ruben could and could not hear. The device has two functions: First, it creates awareness. Outside of the occasional captioned screenings, members of the deaf community often feel isolated by moviegoing, which requires them to ask a theater employee for an awkward device that provides subtitles—a feature designed to be helpful, yet it cannot help but make a deaf person feel different. Second, it enhances the drama’s effect by helping the viewer empathize with Ruben’s situation and that of every deaf person who watches movies. However, if you watch Sound of Metal at home, some streaming services will allow viewers to shut off the subtitles, which misses the point. If you have the option, I recommend leaving them on.

Then again, Marder’s most daring conceit remains the subtitles that, depending on where you watch Sound of Metal, will appear onscreen. When seen theatrically or at festivals, the film came with subtitles that captured what Ruben could and could not hear. The device has two functions: First, it creates awareness. Outside of the occasional captioned screenings, members of the deaf community often feel isolated by moviegoing, which requires them to ask a theater employee for an awkward device that provides subtitles—a feature designed to be helpful, yet it cannot help but make a deaf person feel different. Second, it enhances the drama’s effect by helping the viewer empathize with Ruben’s situation and that of every deaf person who watches movies. However, if you watch Sound of Metal at home, some streaming services will allow viewers to shut off the subtitles, which misses the point. If you have the option, I recommend leaving them on.

Admittedly, Sound of Metal was triggering for me. For most of my life, I’ve dealt with chronic ear infections, blaring tinnitus, and at one point, deafness in one ear, requiring mastoidectomies and ongoing rounds of semi-permanent tubes. Although I have never experienced anything like what Ruben or the other members of his deaf community go through, my hearing has been a constant source of concern, from near-deafness to hypersensitivity. The film became somewhat more relatable for those reasons, while Marder’s sound design proved haunting and familiar. Marder does an exceptional job of putting the viewer in Ruben’s subjectivity, hearing, and, more importantly, not hearing, everything the character does. The effect, combined with Daniël Bouquet’s urgent handheld cinematography, makes us feel present in Ruben’s journey. Of course, Ahmed captures that better than any formal instrument. From Nightcrawler (2014) to HBO’s The Night Of (2016) to The Sisters Brothers (2018), Ahmed has disappeared into his roles, offering complex characters with palpable inner lives.

Both British actors playing Americans, Ahmed and Cooke supply terrific performances, but it’s Raci’s understated, matter-of-fact quality that brings about the biggest emotional outpouring when Joe recognizes that his community cannot help Ruben—or rather, Ruben won’t allow them to help. Although Ahmed and perhaps Cooke will likely receive awards attention for their showier roles, Raci offers credibility by drawing from his personal experience. A curious amalgamation of Joe and Ruben, Raci served in Vietnam, spent some time as a heavy metal musician, and was also the hearing son of deaf parents. He grew up around sign language and the feeling that deafness isn’t an impairment, just a different lifestyle. “Don’t try and fix it,” Joe tells Ruben at one point, and you can see that Raci means it. For hearing members of the audience, that concept may be the most challenging idea in Sound of Metal, and one that continues to resonate long afterward.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review