Sorcerer

By Brian Eggert |

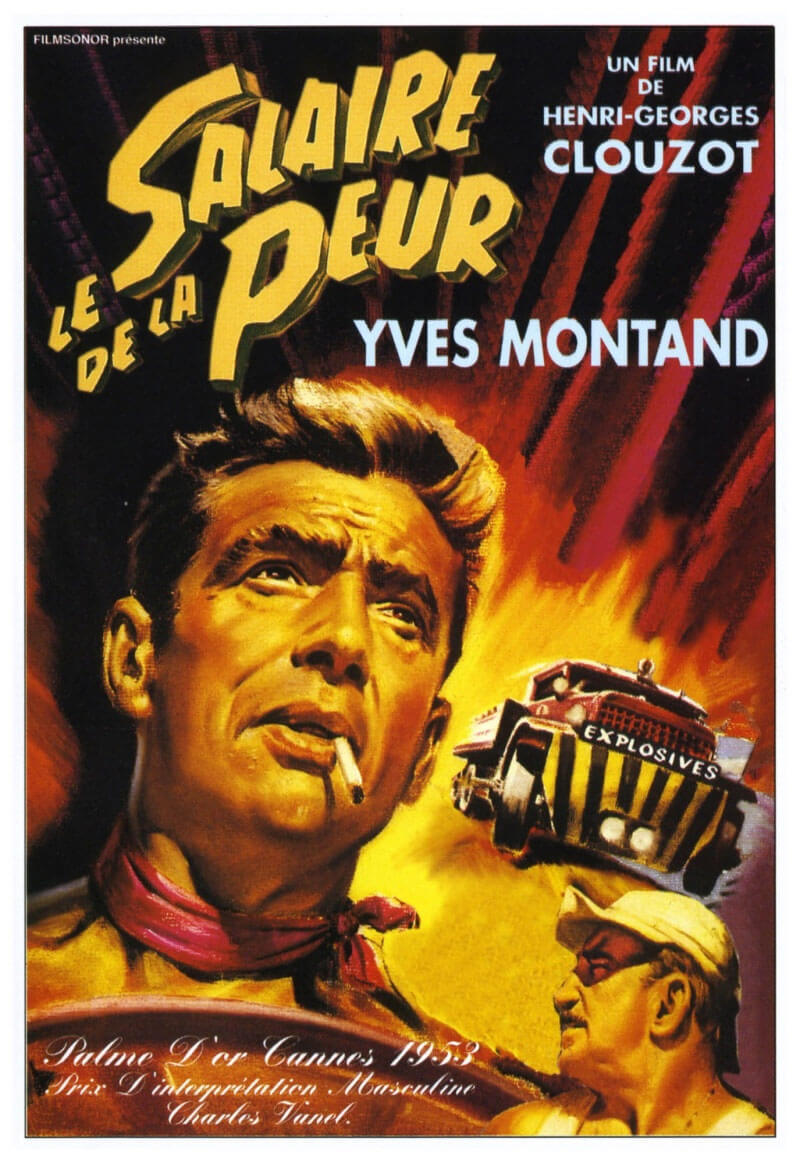

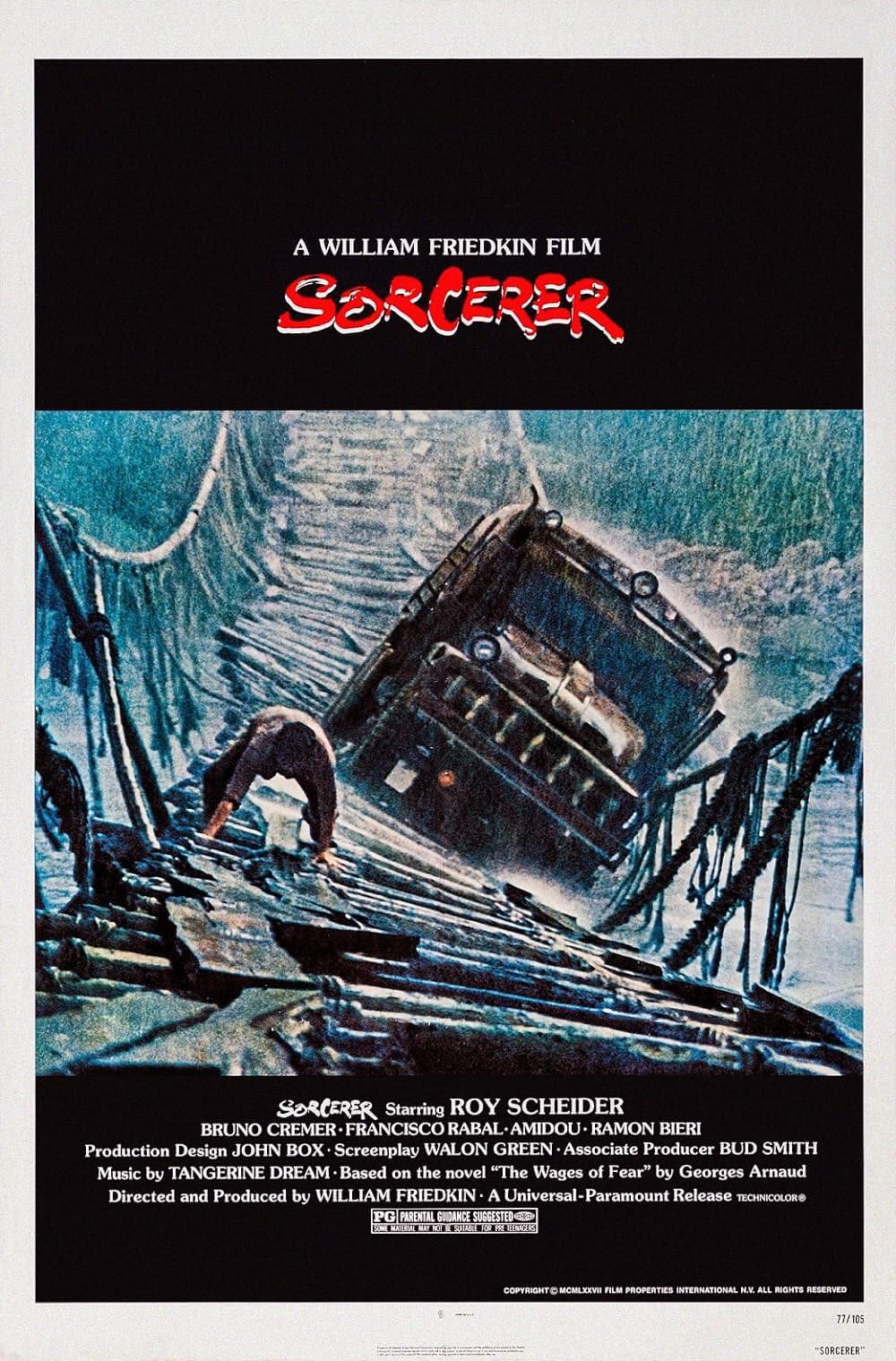

By 1976, William Friedkin had won an Oscar for directing The French Connection (1971) and had been nominated for another on The Exorcist (1973). The filmmaker’s gritty style and personal brashness earned him labels. To some, Friedkin was a chaotic maverick, a reckless master, but also a revolutionary force in 1970s cinema who was often included on lists alongside his contemporary artists like Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola. For his next project, what he considered a minor effort at the time, Friedkin resolved to “reinterpret” Henry-Georges Clouzot’s landmark French thriller The Wages of Fear from 1953, and he sought out The Wild Bunch screenwriter Walon Green to write it. Together, Friedkin and Green took the basic outline from Clouzot’s film, originally based on Georges Arnaud’s 1950 novel Le Salaire de la peur, and turned it into a politicized thriller with existential and docu-styled underpinnings. What was originally planned as a $2.5 million budgeted side project, his eventual film, called Sorcerer, ballooned into a $22 million disaster production, dismissed by both moviegoers and critics. And since its release in 1977, Sorcerer has gone unnoticed by mainstream audiences, and rarely is it entered into the canon of essential 1970s films.

Although Friedkin’s heyday has long since passed—despite recent triumphs with Bug (2007) and Killer Joe (2012)—he’s maintained that Sorcerer is his favorite of his own films. Even with the home video boom of the 1990s and beyond, VHS and DVD copies of the film were distractingly fuzzy, often supplying abridged cuts and rarely in the widescreen format. Indeed, watching Sorcerer in such a state was not watching it at all. Theatrical presentations were rarer still. Only in recent years has Friedkin worked with the original distributors at Universal and Paramount Pictures, who “shared the risk” of the original production, as well as Warner Bros’ home video division, securing the rights to his long “lost” film and supervising a 4K digital restoration from the original negative. The newly restored print debuted at the Venice Film Festival in 2013, and a new Blu-ray release has beautifully showcased what tireless efforts Friedkin and his staff have committed to bringing the film to new life. After watching the Blu-ray, it becomes readily apparent that this critic has never before seen Sorcerer with such urgency or enthusiasm.

As referenced, the story follows its sources closely, whereby four desperate men on the margins of a forgotten South American town agree to drive trucks packed with explosive nitroglycerin across rugged terrain for an uncaring American oil company. Friedkin and Green complicate matters from the outset, politicizing the four outcasts by giving them backstories. Ruthless hitman Nilo (Francisco Rabal) executes a target in Veracruz; Arab terrorist Kassem (Amidou) detonates a bomb at an Israeli bank in Jerusalem; French bourgeoisie Victor Manzon (Bruno Cremer) fails to worm his way out of fraud charges; American wheelman Jackie Scanlon (Roy Scheider) botches a heist of mafia money and becomes a target for the mob. In each case, the four men have something dire to escape from in their homeland, relegating them to the shambled village of Porvenir among similarly dejected ex-Nazis and the dominating economic force of American oil. When an oil well explodes and burns uncontrollably, the foreman (Ramon Bieri) seeks drivers to transport expired, volatile dynamite across 200 miles of jungle. The pay is enough for each desperate man to escape Porvenir, but they have to survive the haul with their cargo, which is highly explosive if disrupted.

As referenced, the story follows its sources closely, whereby four desperate men on the margins of a forgotten South American town agree to drive trucks packed with explosive nitroglycerin across rugged terrain for an uncaring American oil company. Friedkin and Green complicate matters from the outset, politicizing the four outcasts by giving them backstories. Ruthless hitman Nilo (Francisco Rabal) executes a target in Veracruz; Arab terrorist Kassem (Amidou) detonates a bomb at an Israeli bank in Jerusalem; French bourgeoisie Victor Manzon (Bruno Cremer) fails to worm his way out of fraud charges; American wheelman Jackie Scanlon (Roy Scheider) botches a heist of mafia money and becomes a target for the mob. In each case, the four men have something dire to escape from in their homeland, relegating them to the shambled village of Porvenir among similarly dejected ex-Nazis and the dominating economic force of American oil. When an oil well explodes and burns uncontrollably, the foreman (Ramon Bieri) seeks drivers to transport expired, volatile dynamite across 200 miles of jungle. The pay is enough for each desperate man to escape Porvenir, but they have to survive the haul with their cargo, which is highly explosive if disrupted.

Filming in the actual locations, Friedkin demanded realism and shot scenes on busy city streets, in wild sections of Nature rarely seen by human eyes, amid actual terrorist bombings, but primarily in the sweltering jungles of the Dominican Republic. Shooting for authenticity, Friedkin’s picture went wildly over budget from $15 to $22 million, and news that Friedkin had lost control spread throughout Hollywood circles. (In this sense, Friedkin’s approach and obsession with making the film mirrored Werner Herzog’s releases Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) and later Fitzcarraldo (1982), Herzog’s obsessively jungle-shot productions.) When Sorcerer was finally released, it opened within a few weeks of Star Wars, and audiences were hardly in the mood to watch a film steeped in an exaggerated sense of reality and Friedkin’s bleak worldview—a film that alienated its audience and demanded sympathy for criminals on a suicide mission. Worse, Sorcerer‘s posters read “from the director of The Exorcist” and confused viewers who expected magic or fantasy, but Sorcerer was not it (the film’s title comes from the name given to one of the trucks carting dynamite). Variety called it “painstaking, admirable, but mostly distant and uninvolving,” and other critics had much to say about the out-of-control budget. In many ways, Sorcerer would be a precursor to Heaven’s Gate (1980), Michael Cimino’s legendary bomb that forever changed how much artistic license and budgetary freedoms would be given to otherwise proven filmmakers.

Today, the film stands among Friedkin’s best, a profoundly aching work that could only be made with this level of realism and gut-wrenching fatalism in the 1970s. Clouzot’s original remains the superior film, but the distinctions between Sorcerer and The Wages of Fear, in spite of almost identical narrative pathways, are many, and the restored print brings them into finer detail. Most apparent is the film’s bright color palate to contrast Clouzot’s crisp black & white presentation—from the forest’s radiant greens to the purple skies Friedkin found when shooting rocky formations in the Badlands. Aurally, a nightmare quality exists in the picture, in large part due to the score by Tangerine Dream. Before they wrote unearthly-yet-popish music for Michael Mann’s Thief (1981) or Ridley Scott’s Legend (1985), the German synth group had been approached by Friedkin to write their first score for an English-language film. Their electronic beats and low-voltage hums add momentum in the more suspenseful scenes, whereas later, their distant and reverberating synthesizer tones echo the desperation felt by the characters. The overall effect of Sorcerer transplants the audience from any form of safety into an unrelenting cinematic world of desperation, hopelessness, and the ever-present fear of death.

Thematically, the four epilogue scenes for each character leave these individuals difficult to support, and therein Friedkin challenges his audience, daring us to care for bad men. Clouzot’s film simply presented down-on-their-luck men with no histories on the outskirts of civilization, humanity’s lower depths as seen through their desperation and the scenario’s pessimistic outcome. None of the characters in Sorcerer are particularly likable, whereas Clouzot’s film allowed his characters (especially those played by Yves Montand and Charles Vanel) some slight redemption through friendship. Here, one suspects that if Schneider had not starred as the affable Chief Brody in Jaws two years before, the film’s central protagonist would have been irredeemable. Surely the philosophizing early in the picture—”No one is just anything”—applies here, with each character designed to test our limits of empathy. As a result, Sorcerer feels more outwardly dramatized, a more intentionally enhanced slice of grim reality than The Wages of Fear, which held fewer pretensions about its characters. Friedkin, on the other hand, provokes his audience and almost seems to hope that we despise these men.

Thematically, the four epilogue scenes for each character leave these individuals difficult to support, and therein Friedkin challenges his audience, daring us to care for bad men. Clouzot’s film simply presented down-on-their-luck men with no histories on the outskirts of civilization, humanity’s lower depths as seen through their desperation and the scenario’s pessimistic outcome. None of the characters in Sorcerer are particularly likable, whereas Clouzot’s film allowed his characters (especially those played by Yves Montand and Charles Vanel) some slight redemption through friendship. Here, one suspects that if Schneider had not starred as the affable Chief Brody in Jaws two years before, the film’s central protagonist would have been irredeemable. Surely the philosophizing early in the picture—”No one is just anything”—applies here, with each character designed to test our limits of empathy. As a result, Sorcerer feels more outwardly dramatized, a more intentionally enhanced slice of grim reality than The Wages of Fear, which held fewer pretensions about its characters. Friedkin, on the other hand, provokes his audience and almost seems to hope that we despise these men.

But all this talk of fatalism and Friedkin’s veritable self-destructive approach to both the filmmaking process and his film’s themes overlooks the sheer thrills of Sorcerer, which are every bit as plentiful and excruciating as those in The Wages of Fear. Central to the piece is an ambitious sequence where the lumbering trucks plod across a rickety wood and rope suspension bridge (a scene Friedkin called “definitely life-threatening” to make), this during a violent storm over a gushing river. How simple an idea, yet it’s so incredibly well conceived and orchestrated by this master tactician. Along with an agonizing sequence where the foursome detonates a fallen tree with nitroglycerin, Sorcerer pokes and prods its audience throughout, both viscerally and existentially, forcing our complete emotional involvement and eventual exhaustion. Most significantly, this assessment comes after years of greeting the film with indifference due to a subpar video presentation. In its new form, Sorcerer is an altogether new film, and it’s easily one of the best films you’ve never seen; and if you’ve seen it before, you’ve never seen it like this.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review