Song of the Thin Man

By Brian Eggert |

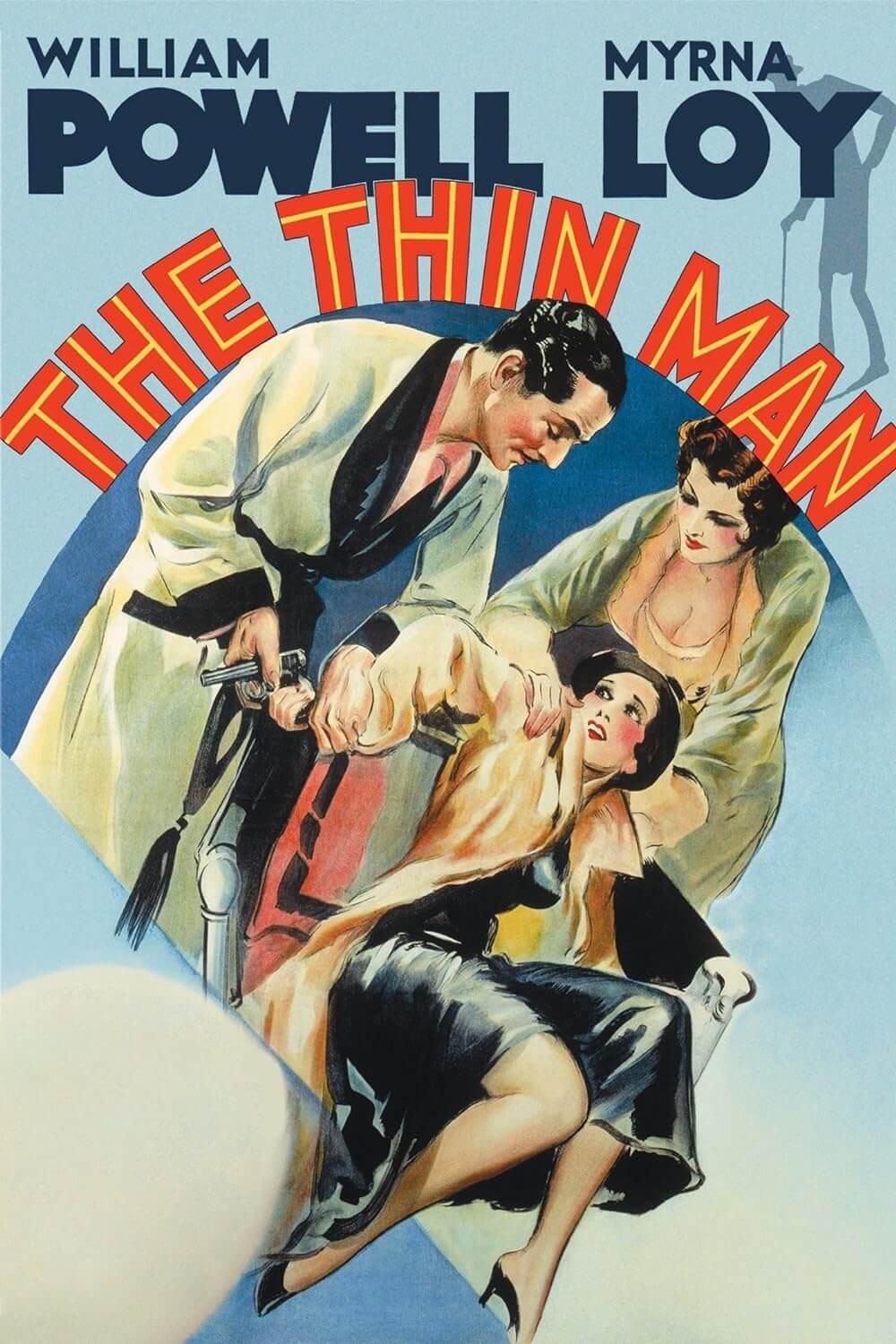

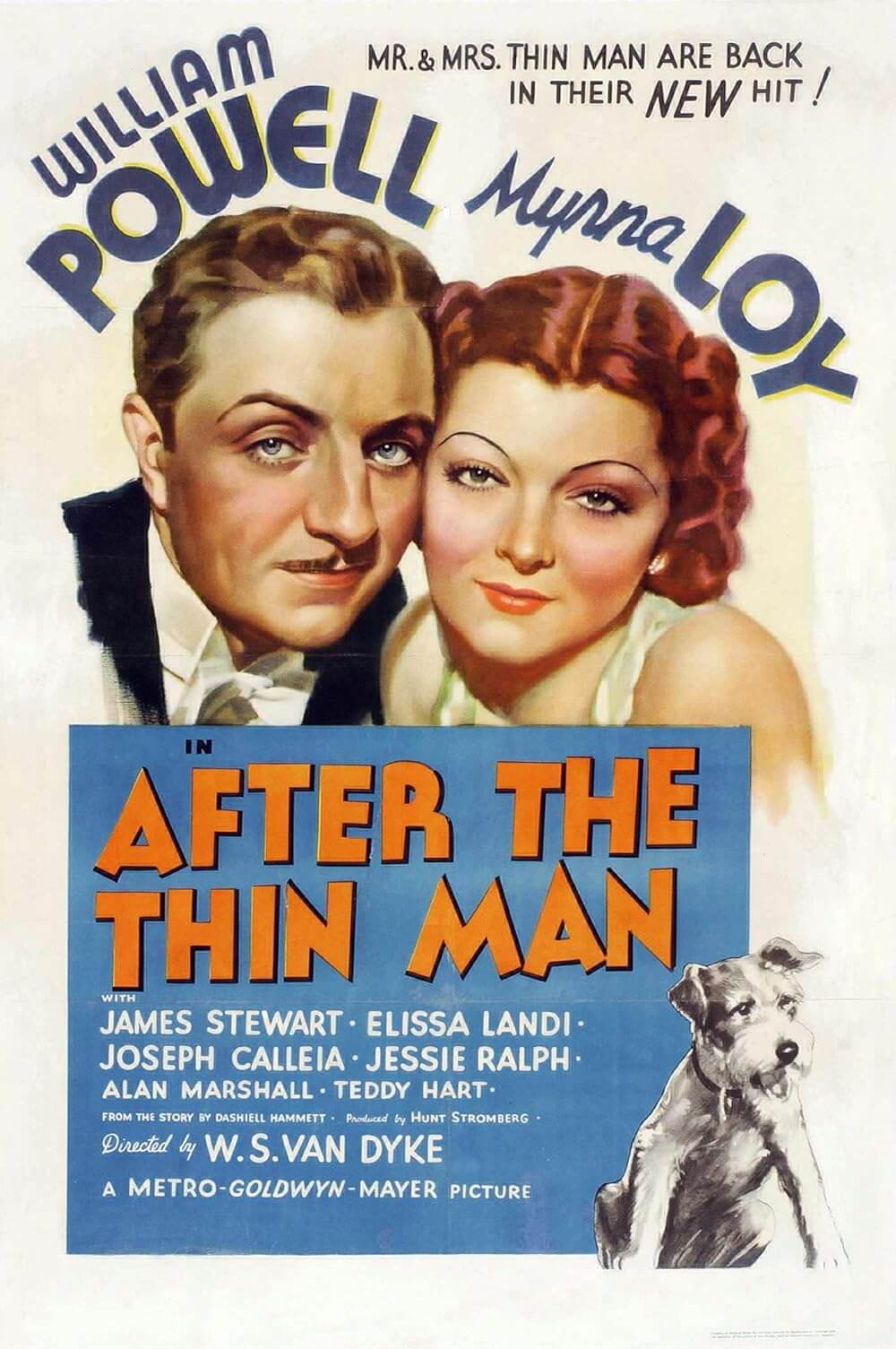

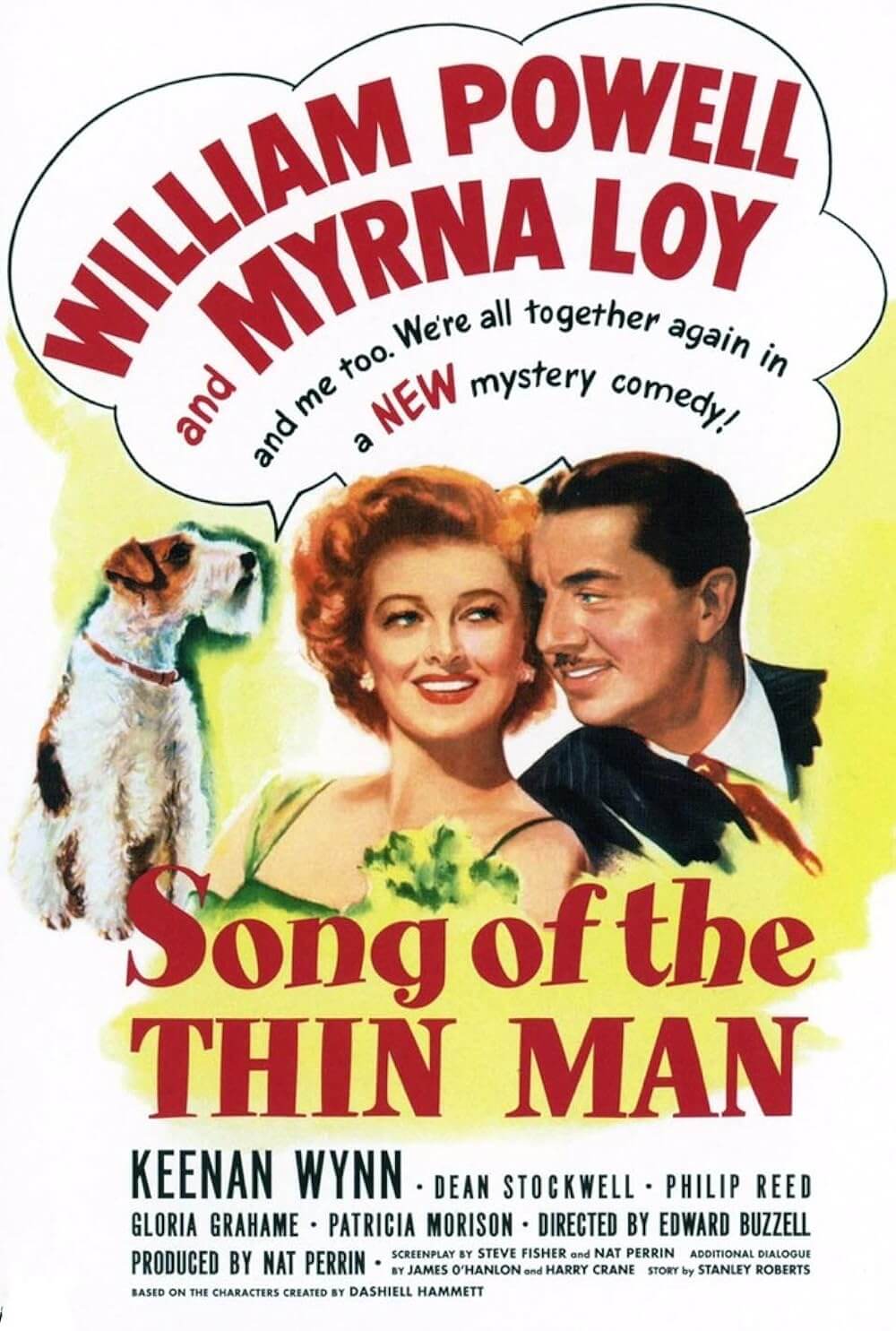

Last but not least of the mystery-comedy series, Song of the Thin Man from 1947 belongs among best of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s six-film franchise, ranking just behind The Thin Man and its first sequel, After the Thin Man. With its tightly constructed mystery and witty repartee standing as some of the best in the series, this sixth entry of “mirth and murder” disproves the theory that sequels only get worse as they go on and distinguishes itself through a unique setting and social climate for the picture, specifically a New York gambling boat and jazz subculture. Although William Powell and Myrna Loy look much older than their fresh-faced appearances in 1934’s original, they’re no less endearing or comically adept as Nick and Nora Charles, cinema’s most gentlemanly detective, and his affectionately inquisitive wife, while their boy Nick Jr. (Dean Stockwell) has become a chip off the old block, and the Charles’ pup Asta is still as sprightly (yet cowardly) as ever. Albeit an unofficial goodbye, the series could’ve hardly asked for a finer send-off.

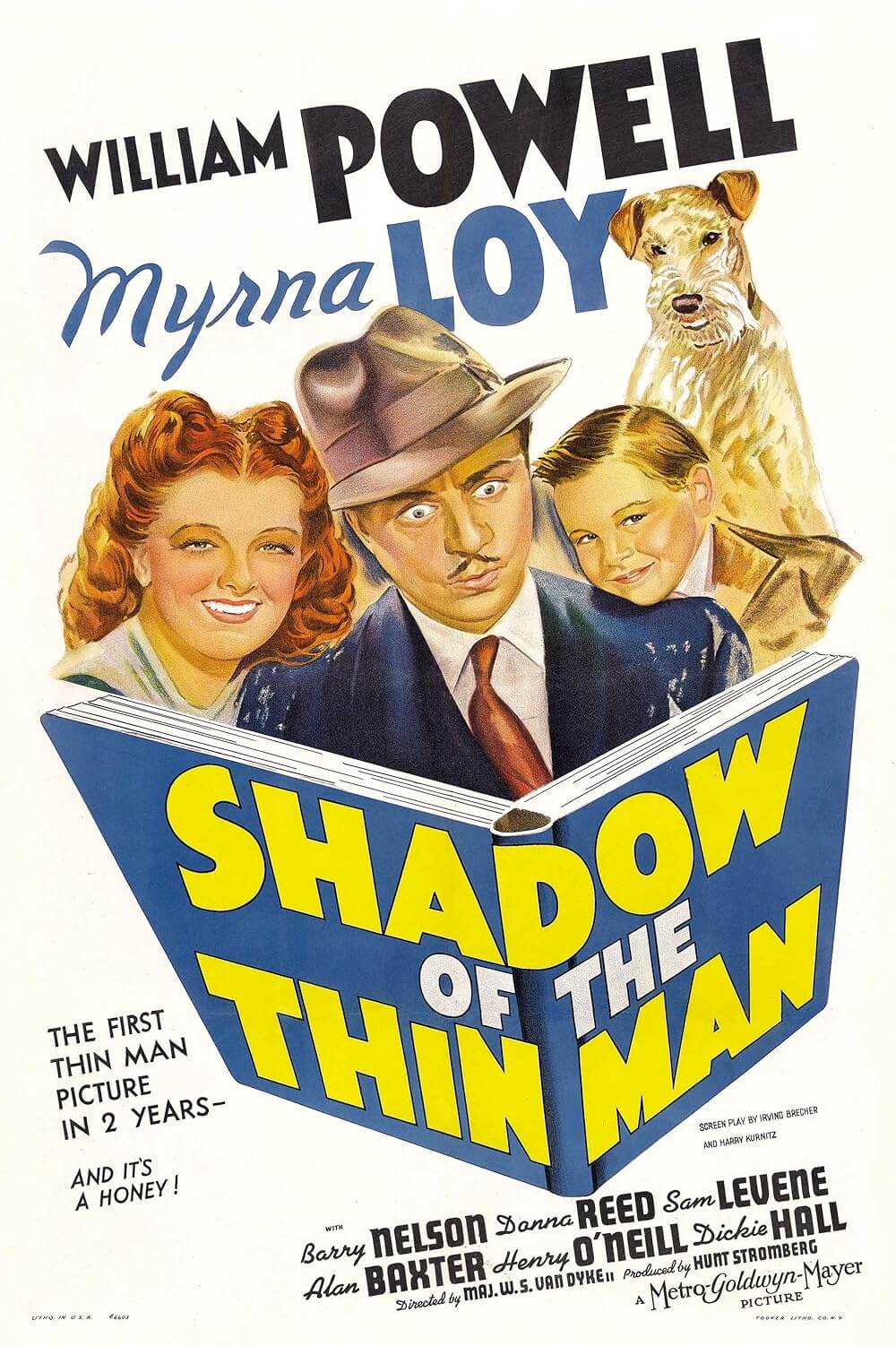

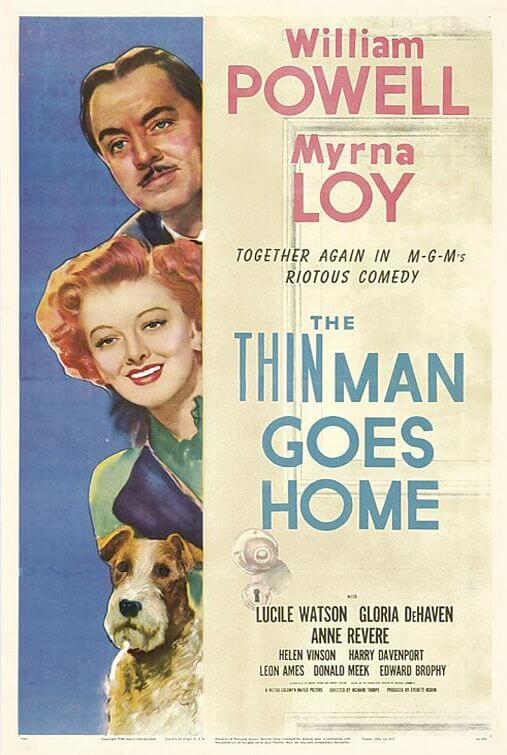

MGM’s wheels were spinning for another Thin Man film after 1945, when the fifth entry The Thin Man Goes Home was released and delivered another financial success for the franchise. Reception of Part 5 wasn’t as strong as previous entries, and so the studio approached an all-new producer to take over. Nat Perrin, who penned (often uncredited) gags and conceived story ideas for the Marx Brothers from 1931 onward, was asked to produce. Perrin also co-wrote with Steve Fisher from a story by Stanley Roberts, all of them far removed from original author Dashiell Hammett or the series’ initial husband-and-wife screenwriters, the Hacketts. As producer, Perrin wanted to appeal to modern audiences and drop Nick and Nora into the fashionable bebop era; he consulted jazz pianist Harry “The Hipster” Gibson to understand the proposed subculture. Gibson would provide the basis for Clarence “Clinker” Krause (Keenan Wynn), the jive-talking hepcat who accompanies Nick and Nora on their investigation into beatnik territory. However modern and distinct the backdrop from the other Thin Man films, it would also unintentionally emphasize how un-modern and out of place Nick and Nora were in such a setting.

To direct, Perrin chose Edward Buzzell, having worked with Buzzell from a distance on minor Marx Brothers efforts like At the Circus (1939) and Go West (1940). Buzzell’s closest film to a Thin Man film was Fast Company (1938), a mystery-comedy about a husband and wife team (Melvyn Douglas and Florence Rice) of rare booksellers who investigate the theft of stolen books and become entangled in a murder mystery. Under Buzzell and Perrin, Song of the Thin Man would go on to make profits for MGM, but along with their Tarzan series, the studio resolved to end while they were ahead. In her autobiography Being and Becoming, Loy had much to say about the film. “[It was] a lackluster finish to a great series. I hated it. The characters had lost their sparkle for Bill and me,” she admitted, though this isn’t evidenced onscreen. “The people who knew what it was all about were no longer involved. Woody Van Dyke was dead. Dashiell Hammett and Hunt Stromberg had gone elsewhere. The Hacketts were writing other things.” Loy went on to observe the film’s favorable reception, “According to the Hollywood Reporter, ‘Most of the cricks gave a cordial welcome to old-timers Bill Powell and Myrna Loy. . . .’ I know that only because Bill sent me the article with ‘old-timers’ circled in pencil and this note scrawled at the top of the page: ‘Dear old girl! I know you wouldn’t want to miss this! Love, Willy (old boy).” Loy’s feelings about Song of the Thin Man were shared by many, but the film has aged well and, when measured up against its immediate three predecessors, contains an immediacy the others lack.

To direct, Perrin chose Edward Buzzell, having worked with Buzzell from a distance on minor Marx Brothers efforts like At the Circus (1939) and Go West (1940). Buzzell’s closest film to a Thin Man film was Fast Company (1938), a mystery-comedy about a husband and wife team (Melvyn Douglas and Florence Rice) of rare booksellers who investigate the theft of stolen books and become entangled in a murder mystery. Under Buzzell and Perrin, Song of the Thin Man would go on to make profits for MGM, but along with their Tarzan series, the studio resolved to end while they were ahead. In her autobiography Being and Becoming, Loy had much to say about the film. “[It was] a lackluster finish to a great series. I hated it. The characters had lost their sparkle for Bill and me,” she admitted, though this isn’t evidenced onscreen. “The people who knew what it was all about were no longer involved. Woody Van Dyke was dead. Dashiell Hammett and Hunt Stromberg had gone elsewhere. The Hacketts were writing other things.” Loy went on to observe the film’s favorable reception, “According to the Hollywood Reporter, ‘Most of the cricks gave a cordial welcome to old-timers Bill Powell and Myrna Loy. . . .’ I know that only because Bill sent me the article with ‘old-timers’ circled in pencil and this note scrawled at the top of the page: ‘Dear old girl! I know you wouldn’t want to miss this! Love, Willy (old boy).” Loy’s feelings about Song of the Thin Man were shared by many, but the film has aged well and, when measured up against its immediate three predecessors, contains an immediacy the others lack.

The film opens on the S.S. Fortune, a posh gambling boat on which Nick and Nora are introduced when a pair of Nick’s less reputable friends make eyes at Nora from behind. “Woo-whoo!” one of them says. Nick turns in reply, “In polite society, it’s not ‘Woo-whoo’. It’s pronounced ‘Woo-whom’.” When we first see them, Powell and Loy have aged much since The Thin Man Goes Home. Powell is a little wide around the midsection and there are crows feet in the corners of Loy’s eyes, but he’s still debonair and she’s as beautiful as ever. Over the course of the evening, we meet blonde vixen Fran Page (Gloria Grahame), singer for the band, which includes clarinetist Buddy Hollis (Don Taylor) and bandleader Tommy Drake (Philip Reed), who are quarreling over Fran’s affections. Tommy has enemies elsewhere too. He owes $12,000 to bookie Al Amboy (William Bishop), threatens to break his band’s contract with the ship’s owner Phil Brandt (Bruce Cowling) to tour for promoter Mitch Talbin (Leon Ames), and seems to be in bed with Ames’ wife Phylis (Patricia Morrison). When Tommy ends up dead, shot to death in Phil Brandt’s office, the suspects are many. Brandt’s new wife Janet Thayer (Jayne Meadows), whose wealthy father (Ralph Morgan) doesn’t approve of their elopement, suggests that famous former detective Nick Charles investigate.

In past Thin Man films, the writers saw Nick Jr. as a nuisance and included the character only because they couldn’t ignore him (then again, that’s just what The Thin Man Goes Home did) after the Hacketts saddled the Charleses with a child. Song of the Thin Man makes the most of the character in a hilarious if somewhat cartoonish sequence over breakfast. Nick Jr. demonstrates that his father’s streetwise wiliness has rubbed off, referring to a woman as a “broad” and then later shirking his studies to go play. Nick is begrudgingly forced to reprimand the boy with a spanking, but with Nick Jr. over his knee, Nick hesitates and daydreams, remembering fond father-son bonding moments in a dream bubble over Nick Jr.’s bottom. As Nora looks on disappointedly, all at once, Nick recalls when he fell off a bike and Nick Jr. laughed at him—and then proceeds to enthusiastically correct the boy with a newspaper, only to discover Nick Jr. has padded himself with a baseball glove. “That was very clever of you,” Nora concedes approvingly. As parents, the carefree Nick and Nora find themselves apologizing to their son for their late nights out and gallivanting about town, but when Nick Jr. is believed in danger, the hour-long train ride home shows the parents in desperation.

Song of the Thin Man‘s story structure allows the usual Thin Man formula to play out naturally. Rather than call the usual suspects to an enclosed room for a grand finale, Nick arranges for everyone to gather on the S.S. Fortune again—an equally condensed space—where our hero solves the whodunit by pulling the strings on paranoid characters. Nora has her moment of resourcefulness too when, earlier in the film, she slips away to interview the key witness, Buddy, who’s gone barmy in a sanitarium. She finds herself alone with a madman. Taylor’s manic-eyed performance as Buddy and Grahame’s turn as the resident femme fatale (before her roles in The Big Heat and In a Lonely Place) decked out in a sleek gold-lame dress, become two of the film’s most interesting performances. Still, the graceful charm of Powell and Loy reminds us why they’re the screen’s most venerable, most sophisticated duo. Any detractors accusing Powell and Loy of not having their hearts in their performances aren’t watching closely enough. At the time of the film’s release, Powell and Loy were doing some of their best screen work, Powell in Life With Father (1947) and Loy in The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), and their talent isn’t wasted here.

Song of the Thin Man‘s story structure allows the usual Thin Man formula to play out naturally. Rather than call the usual suspects to an enclosed room for a grand finale, Nick arranges for everyone to gather on the S.S. Fortune again—an equally condensed space—where our hero solves the whodunit by pulling the strings on paranoid characters. Nora has her moment of resourcefulness too when, earlier in the film, she slips away to interview the key witness, Buddy, who’s gone barmy in a sanitarium. She finds herself alone with a madman. Taylor’s manic-eyed performance as Buddy and Grahame’s turn as the resident femme fatale (before her roles in The Big Heat and In a Lonely Place) decked out in a sleek gold-lame dress, become two of the film’s most interesting performances. Still, the graceful charm of Powell and Loy reminds us why they’re the screen’s most venerable, most sophisticated duo. Any detractors accusing Powell and Loy of not having their hearts in their performances aren’t watching closely enough. At the time of the film’s release, Powell and Loy were doing some of their best screen work, Powell in Life With Father (1947) and Loy in The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), and their talent isn’t wasted here.

Despite the danger of making Nick and Nora look outdated when compared to the contemporary jazz underground, today, it’s evident that Song of the Thin Man looks on with comic misgivings and instead aligns with our enduring married couple. In one sequence at a late-night jam, Nick and Nora pose as hipsters amid a smoky, bopping party of musicians and jazz aficionados. Though they clearly don’t belong, the camera moves from the Charleses, across a room of gyrating musicians, to a familiar bust resting on a piano—it’s Beethoven, holding his signature scowl, seemingly aching over the organized aural chaos around him. Indeed, jazz culture itself is suspect, while Nick and Nora are their hallmark selves, as delightful and timeless as the best screen couples along with Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, and Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn. William Powell and Myrna Loy would make one more film together, the forgettable The Senator Was Indiscreet, also from 1947, but Song of the Thin Man would sing a more appropriate farewell. Once the murder is solved, Nick says, “Now Nick Charles is going to retire.” Nora asks, “You’re thru with crime?” “No,” says Nick. “I’m going to bed.”

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review