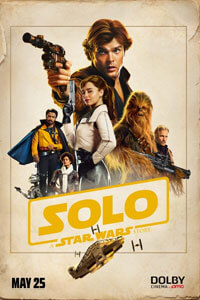

Solo: A Star Wars Story

By Brian Eggert |

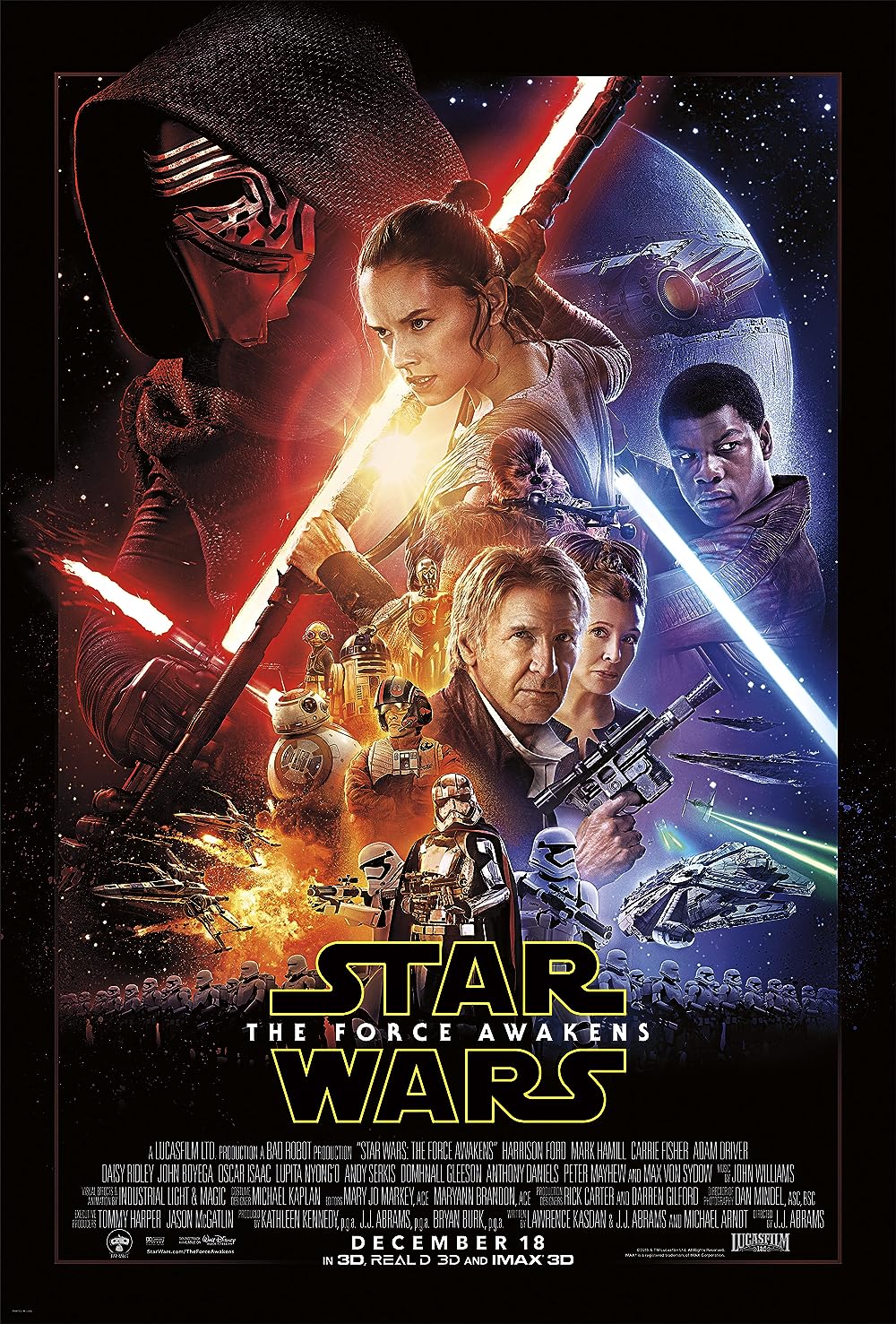

The Star Wars franchise has been through some dramatic changes since Walt Disney Studios acquired the intellectual property from Lucasfilm. Although mostly celebrated, fans accused Star Wars: Episode VII – The Force Awakens (2015) of being little more than a reboot of the 1977 original, complete with another planet-sized weapon and a promising young Jedi. Next came Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (2016), a cash-grab spinoff designed to fill in the blanks on how Princess Leia first received plans to destroy the Death Star, while offering meager contributions to the mythology. The most divisive entry yet, Star Wars: Episode VIII – The Last Jedi (2017) put forth significant changes to characters, storylines, and franchise tonality that left many angered by its departures. (If all the Star Wars films appeared on Sesame Street‘s “Which one of these doesn’t belong” game, The Last Jedi would be it.) Disney’s Star Wars films have one thing in common besides the obvious source material; they each feel like fan fiction—with filmmakers trying to approximate the look and feel of George Lucas’ Star Wars universe. But none so far proves as inessential to the mix as Solo: A Star Wars Story.

The second entry under the label “A Star Wars Story,” Solo provides an origin to the beloved Han Solo, everyone’s favorite intergalactic smuggler played by Harrison Ford, who retired from the role after the character’s death in The Force Awakens. The screenplay, penned by Lawrence Kasdan and his son, Jonathan, follows a young Han Solo, played by Alden Ehrenreich (from Hail, Caesar! and Rules Don’t Apply), as he develops from a fledgling pilot into a scruffy-looking nerf herder. But anticipation for Solo has been marred by highly publicized production troubles. Among the reported difficulties, co-directors Phil Lord and Chris Miller were replaced by journeyman director Ron Howard, after executive producer Kathleen Kennedy cited ever-ambiguous “creative differences” with the duo behind The LEGO Movie. Reports from the set suggest an initial chaotic atmosphere, while Ehrenreich was assigned an acting coach after he failed to replicate Ford’s charisma. Eventually, Howard, a consummate and experienced professional, is said to have brought a sense of relaxed control to the production’s early chaos after expensive reshoots.

But reviewing a troubled production story isn’t the goal here, especially since the primary faults of Solo reside in the script, as opposed to the filmmaking or acting. While many cinephiles watched Steven Spielberg’s release this year, Ready Player One, and complained that it’s a feature too dependent on Easter eggs (knowing reference points to other material, inserted to please fans), Solo is a film whose plot is strung together by connecting one reference point to the next. At least the Easter eggs in Ready Player One remained superfluous, and the narrative trajectory existed on its own merits. The Kasdans’ script has been written around the details of Han Solo from previous films and answers a series of trivial questions: How did Han get his last name? Where did he meet Chewbacca and Lando Calrissian? Can Han really speak Wookie? Why does Lando pronounce our hero’s name as “Han” instead of “Hahn”? Where did Han obtain his signature blaster? How did Han acquire the Millenium Falcon? What exactly is the “Kessel Run,” and why is it significant that it was completed in just 12 parsecs? Why does the Millenium Falcon look like a bucket of bolts? Did Han always shoot first? Not one of these questions is imperative to understanding Han Solo, in part because the character was already well defined without knowing these details. As such, the screenplay’s incessant need to wink at the audience with this filling-in-the-blanks approach becomes predictable and mundane.

But reviewing a troubled production story isn’t the goal here, especially since the primary faults of Solo reside in the script, as opposed to the filmmaking or acting. While many cinephiles watched Steven Spielberg’s release this year, Ready Player One, and complained that it’s a feature too dependent on Easter eggs (knowing reference points to other material, inserted to please fans), Solo is a film whose plot is strung together by connecting one reference point to the next. At least the Easter eggs in Ready Player One remained superfluous, and the narrative trajectory existed on its own merits. The Kasdans’ script has been written around the details of Han Solo from previous films and answers a series of trivial questions: How did Han get his last name? Where did he meet Chewbacca and Lando Calrissian? Can Han really speak Wookie? Why does Lando pronounce our hero’s name as “Han” instead of “Hahn”? Where did Han obtain his signature blaster? How did Han acquire the Millenium Falcon? What exactly is the “Kessel Run,” and why is it significant that it was completed in just 12 parsecs? Why does the Millenium Falcon look like a bucket of bolts? Did Han always shoot first? Not one of these questions is imperative to understanding Han Solo, in part because the character was already well defined without knowing these details. As such, the screenplay’s incessant need to wink at the audience with this filling-in-the-blanks approach becomes predictable and mundane.

The film opens on a Dickensian planet of Corellia, where young, waifish thieves operate in a dark underbelly for a Fagan-like centipede crimelord. Han (Ehrenreich) and his love, Qi’ra (Emilia Clarke), attempt to escape together, but they’re separated—Han flees and joins the Imperial army to become a pilot so he can return and rescue Qi’ra, while she remains in the clutches of Corellian goons. After a stint in the army and fighting in the trenches, Han deserts and teams up with a ragtag group of bandits to carry out a train robbery for a gangster. Inevitably, their robbery goes south and requires them to carry out an even more dangerous, potentially disastrous plan filled with twists and turns. Solo’s screenplay was decidedly shaped by a combination of classical Westerns and gangster pictures, following a nobody on his rise to become an outlaw. The atmosphere of shady personalities, double-crosses, and pure adventure does much to pull the viewer into the proceedings.

But more interesting than Han himself is the cast of the supporting characters, foremost being Chewbacca (played by Joonas Suotamo) who, somehow, through throaty moans and intense hand-to-hand combat, exudes heart and devotion. When the two partner with Tobias Beckett (Woody Harrelson, who never disappears into his role), a criminal gang leader, Han finds his mentor. Beckett’s crew consists of his wife Val (Thandie Newton), a no-nonsense professional thief, and the CGI character Rio Durant (voiced by Jon Favreau), their four-armed alien pilot. They’re soon joined by Lando (Donald Glover, doing a fine impression of Billy Dee Williams) and his companion L3-37 (Phoebe Waller-Bridge), a self-aware droid who’s determined to achieve equal rights for droids everywhere. They’re all working to obtain the film’s McGuffin, the high-powered fuel coaxium, for a ruthless overlord named Dryden Vos (Paul Bettany, having fun with his role).

Howard’s direction, as always, proves capable, if also generic and unexceptional. Scenes of action have serviceable energy to them, and the score by John Powell, heavily informed by John Williams’ themes, keeps the viewer fixed in the Star Wars milieu. The problem has nothing to do with form or execution; the film is a $250 million production, and it looks like it. The problem, as stated, subsists in the script and, perhaps, the basic concept of a Han Solo prequel story. The dull requirement to demystify the character and transcribe for the audience every mysterious detail associated with him robs the material of its joy and originality. For instance, consider Han’s last name and how it’s achieved. “Solo” is already an on-the-nose moniker, given the character’s frequent declarations of independence (“I take orders from just one person: me.”). How he came by his surname is even more bromidic. The film suggests that, when Han joined the Imperial army, a random admittance guard asks Han his last name, but he doesn’t have one. The guard ponders this and then, quite pleased with himself, types in S-O-L-O. (Get it? Because he’s solitary, on his own, unaccompanied, friendless, stag, and by himself.) How deeply uninspired. Solo is a film strung together by moments such as this, and the few wrinkles and revelations in the plot cannot overcome their hokeyness.

The continued devotion among moviegoers to the Star Wars franchise remains baffling, even odd to me. Omitting the conveniently forgotten TV movies Caravan of Courage: An Ewok Adventure (1984) and Ewoks: The Battle for Endor (1985), there are now ten Star Wars films. Out of those ten, only four titles have been (for the most part) universally praised by fans, including the original trilogy and The Force Awakens. More than half of the titles have incurred indifference, disappointment, or downright loathing. This leaves a franchise that has a lousy track record but still commands the allegiance of millions of viewers the world over. It’s a phenomenon that becomes increasingly difficult to explain as the years pass and the films continue to be inconsistent or underwhelming. Disney adds to the growing disenchantment by loading their production schedule with a new Star Wars film every year, making each new entry a little less precious, and therein robbing the franchise of its status as a cultural event (instead, there’s just a wincing sense of “What next?”). Of course, my cynicism and views on the state of Star Wars is a minority opinion and should be taken as such.

Solo: A Star Wars Story doesn’t advance the legacy of the franchise or even make Han Solo more beloved; quite the opposite. Han Solo is less interesting by the end. Given that an audience already knows what becomes of Solo, Chewbacca, and Lando later in life, the stakes in the film remain limited. It’s not as though scenes of peril will be deadly for anyone involved, except the newly introduced characters, most of whom die and, of course, have no bearing on the existing films. Much like the other Disney-produced entries, the result plays like expensive fan fiction by existing within a limited narrative bubble that allows the characters insufficient room to maneuver or grow. Moreover, Solo demonstrates that demystification by prequel is Hollywood’s most banal trend at present, and it’s ruining Disney’s Star Wars output. The film, while capably made by Howard and playfully performed by the cast, has little consequence, and this is quickly becoming the case with each of Disney’s Star Wars films.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review