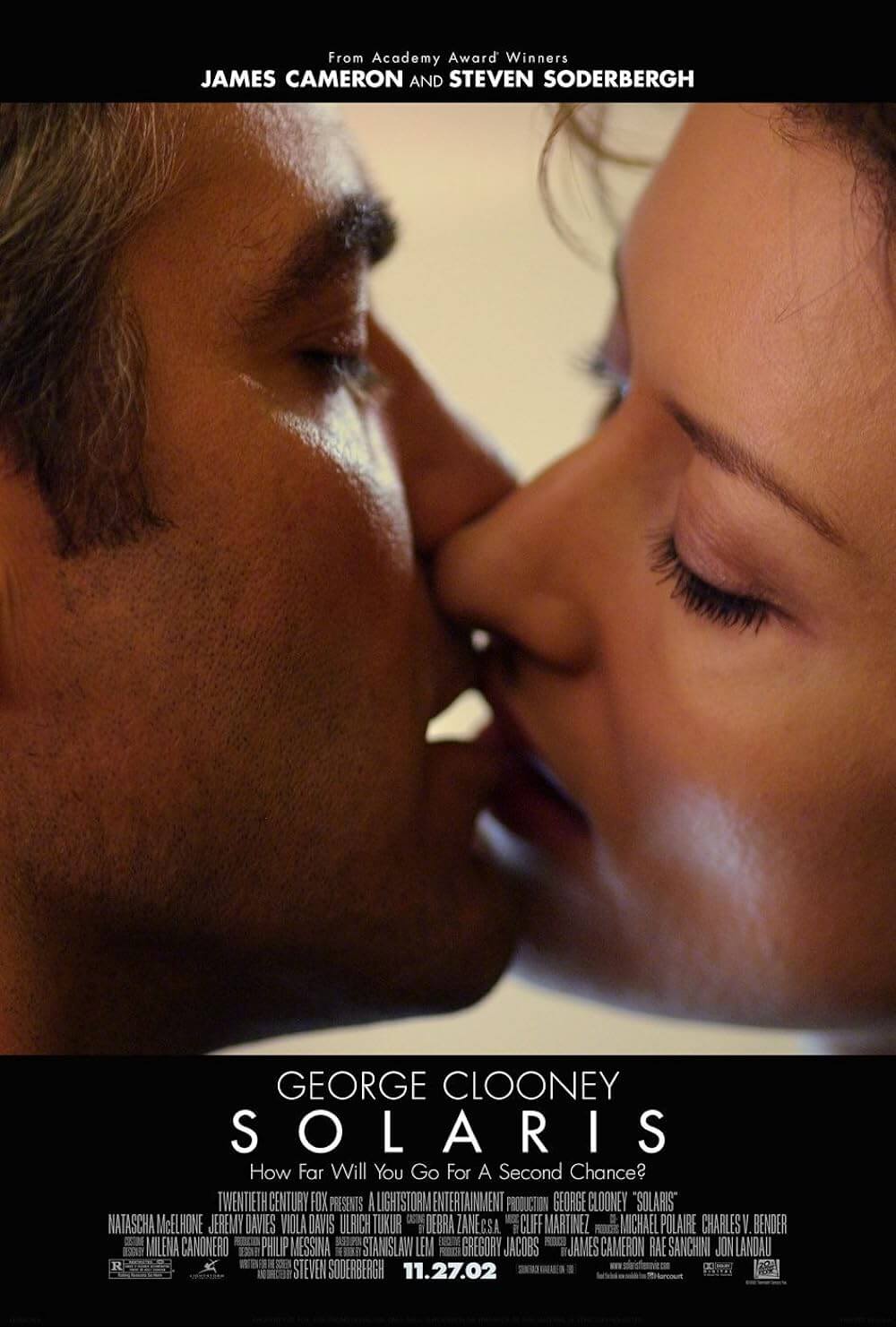

Solaris

By Brian Eggert |

Though not much is revealed about the proposed science-fiction art film from Italian auteur Guido Anselmi (Marcello Mastroianni), the artistically and emotionally blocked protagonist of Federico Fellini’s 8 ½ (1963), when I imagine what it would be, I think of Steven Soderbergh’s Solaris from 2002. Based on the same 1961 novel by Polish author Stanisław Lem that inspired Andrei Tarkovsky’s masterful 1972 adaptation, Soderbergh’s film is about love, guilt, and memory. It’s an expensive, A-list production starring George Clooney at the height of his celebrity. Nonetheless, it belonged on arthouse theater screens, not in the multiplexes where it went underseen and misunderstood by mainstream audiences. Critics, too, received the project with lukewarm praise at the time, but upon reassessment, this pensive and melancholic picture challenges its audience in the most substantive of ways. And of course, Soderbergh’s treatment of the material is technically efficient, yet always affecting. He embraces the science-fiction elements of the story, sets aside Tarkovsky’s intricate formal meditation on time, and creates a thoughtful, emotionally raw picture that achieves the loftiest ambitions of the science-fiction genre.

In the mid-1990s, James Cameron’s production company Lightstorm Entertainment pursued the rights to Lem’s novel, as the director of The Terminator (1984) was interested in tackling a new adaptation. When Cameron became immersed in other projects (several post-Titanic undersea documentaries and the TV series Dark Angel), he sought another filmmaker to take the helm. Steven Soderbergh had emerged from his experimental period in the ’90s with a series of commercial hits. He demonstrated that George Clooney had major movie star charisma with Out of Sight (1998), helped earn Julia Roberts her Oscar for Best Actress on Erin Brockovich (2000), and that same year earned himself the Best Director Oscar for Traffic. After delivering a blockbuster with his all-star heist-comedy Ocean’s 11 (2001), Hollywood was willing to take risks on Soderbergh’s more unusual ideas, even if they occasionally proved to be failures (see Full Frontal, 2002). Soderbergh pitched his version of Solaris to Cameron in 1999, and after an enthusiastic response from Cameron’s team at Lightstorm, the production went into development with Soderbergh as writer-director.

Ever the economic and precise filmmaker, Soderbergh’s production, which cost around $47 million, began principal photography in May 2002 and was released the following November—a staggeringly short turnaround for this scope of a film. Clooney, who was not Soderbergh’s first choice for the role (Daniel Day-Lewis was busy shooting Martin Scorsese’s Gangs of New York), but who committed himself to the emotional preparation required for the character, would become the focus of the film’s marketing campaign. More specifically, Clooney’s butt. The actor himself admitted that the distributors didn’t know how to sell the film, so they resolved to publicize how Clooney’s bare bottom makes an appearance in this cosmic love story. Audiences weren’t interested in Clooney’s butt, as it turns out. The film earned only $30 million in U.S. box-office receipts, perhaps influenced by the mixed critical reception. Using words like “sophisticated” and “cerebral” in their assessments, the critics who favored Solaris—among them Roger Ebert, Andrew Sarris, J. Hoberman, and Kenneth Turan—did little to sell the picture to Average Joe Moviegoer. The dissenters were more aligned with audiences, such as Stephen Hunter of the Washington Post, who called the film, “One for the graduate students who know everything about movies except how to enjoy them.” Indeed, the commercial expectations of most could hardly digest the intricacies of Soderbergh’s adaptation, nor did they want to.

To call Soderbergh’s adaptation different than Tarkovsky’s would be an understatement. Soderbergh concentrates on the story and its emotions. His efficient writing and scenes do not linger; his camerawork is intimate; he cuts through the same narrative material as Tarkovsky’s 165-minute epic, using a mere 98 minutes to deliver a more accessible, but not less complicated story. Tarkovsky never embraced the story and its genre. He used the material to continue his formal examination of how time and memory can be represented with the cinematic apparatus. Tarkovsky was intrigued by the formal possibilities facilitated by the story—where time, memory, and emotion could be manipulated and evoked within a single shot. He nonetheless remained resistant to the science-fiction tropes that drove the material. “I do feel that Solaris is the least successful of my films,” Tarkovsky said later, “because I was never able to eliminate the science-fiction association.” Tarkovsky’s low view of the genre speaks to his interests in cinema as a formal art first, a narrative art second. Soderbergh’s approach is just the opposite; he creates a unity between the narrative and genre so they remain inextricable from one another. With Tarkovsky’s film, the viewer might forget they’re watching a work of science-fiction; in Soderbergh’s version, there’s no mistaking the genre.

To call Soderbergh’s adaptation different than Tarkovsky’s would be an understatement. Soderbergh concentrates on the story and its emotions. His efficient writing and scenes do not linger; his camerawork is intimate; he cuts through the same narrative material as Tarkovsky’s 165-minute epic, using a mere 98 minutes to deliver a more accessible, but not less complicated story. Tarkovsky never embraced the story and its genre. He used the material to continue his formal examination of how time and memory can be represented with the cinematic apparatus. Tarkovsky was intrigued by the formal possibilities facilitated by the story—where time, memory, and emotion could be manipulated and evoked within a single shot. He nonetheless remained resistant to the science-fiction tropes that drove the material. “I do feel that Solaris is the least successful of my films,” Tarkovsky said later, “because I was never able to eliminate the science-fiction association.” Tarkovsky’s low view of the genre speaks to his interests in cinema as a formal art first, a narrative art second. Soderbergh’s approach is just the opposite; he creates a unity between the narrative and genre so they remain inextricable from one another. With Tarkovsky’s film, the viewer might forget they’re watching a work of science-fiction; in Soderbergh’s version, there’s no mistaking the genre.

The film takes place in a future constructed with flat, lifeless surfaces and drab-gray clothing, all plastic-looking, and drenched in perpetual rainfall. Clooney plays Chris Kelvin, a practicing psychologist with group therapy sessions and active patients (unlike Donatas Banionis’ version of the character, who seemed to be a psychologist in name only). Early on, Chris receives a message from his friend, Gibarian (Ulrich Tukur), a scientist on a space station orbiting the planet Solaris, to come and evaluate some strange phenomena influencing the station’s crew. Officials had already sent a security force to the station, but they have lost contact. With nothing tying him to Earth, Chris agrees. When he arrives at the station, he finds it eerily still. A trail of dried blood leads to the morgue, where he discovers three dead bodies, including Gibarian, who has committed suicide. A characteristically mannered Jeremy Davies (“Yeah… How about that?”) plays Dr. Snow, who provides vague, non-explanations for their situation: “I could tell you what’s going on, but that wouldn’t tell you what’s going on.” Another doctor was killed, another disappeared to who-knows-where, and yet another, Dr. Gordon (Viola Davis), has locked herself in her room. Also, somewhere on the ship, a small boy is loose.

The dread that subsists beneath these early scenes gives way to terror and confusion after Chris sleeps for the first time on the station. Soderbergh, serving as editor under his pseudonym Mary Ann Bernard, cross-cuts between Chris’ memories, his sleep, and the planet whose electric currents flow into one another—a planet that “knows it’s being observed,” according to one scientist. Chris’ dreams introduce us to his late wife, Rheya (Natasha McElhone), who killed herself some years earlier. When he rouses from his dream, Rheya is somehow there. They make love, perhaps because he thinks he’s still dreaming. Perhaps he is. And when he really wakes up, the sight of her frightens him out of bed. He steps away, touching the cold surfaces of his space station quarters to prove to himself he’s awake, and braces himself to look at her. With a single, wounded glance, Clooney proves he’s capable of much more emotional depth than he had shown at that point in his career. What’s fascinating about this scene is how Chris begins to dissect her presence from a psychologist’s point-of-view. He asks where she thinks she is, what she remembers, and tries to determine what he’s looking at. Is this really Rheya? He approaches the situation as a scientist would, but more urgently, trying to shield himself from the profound emotions surging beneath his façade.

Rheya is one of many “visitors” that Solaris has brought to life by mining the unconscious desires and memories of the station’s crew. But she’s also self-conscious and aware of her own deficiencies. Each of the scientists has experienced a similar visit from someone close to them. However, as many have learned by trying to kill or eradicate their visitor, Solaris simply resurrects or replaces visitors as the crew sleeps. Chris, too, discovers this after ejecting his Rheya visitor into space inside an escape pod. (“Will she come back?” he asks Snow. “Do you want her to?” is Snow’s cryptic reply.)

Of course, the next time Chris awakes from his sleep, another Rheya is waiting for him, confused about her presence on the station and stricken by the traumatic memories from Chris’ mind. Soderbergh’s most effective alteration in his version is the amount of screentime he spends in Chris’ memories, establishing the emotional basis of Chris and Rheya’s relationship. The director invests his audience by showing us how they met, fell in love, and ultimately were torn apart when, after discovering she’s pregnant, Rheya rids herself of the burden. When Chris learns of this, he abandons her. Rheya, having been established as sensitive and unpredictable, kills herself. As a visitor, Rheya remembers herself as Chris remembers her, volatile and suicidal. The visitor tries to drink liquid oxygen to end her life, but Solaris brings her back.

Clooney and McElhone’s performances reveal wounded characters, visitors or otherwise, caught in a tragic, unsolvable problem. Chris, stricken with guilt over Rheya’s death, desperately wants a second chance to correct his mistake. The Rheya-visitor acknowledges her own artificiality and questions the authenticity of her being. She knows her very existence has been informed by Chris’ memories. Worse, what if Chris has remembered her incorrectly? There must be a solution, Chris believes. But Solaris wants nothing. There is no intended outcome to this situation, no objective. It’s a natural occurrence. Such complicated emotional conditions allow Clooney to become a far more expressive, passionate actor in this role than he’s ever been before or since. The same is true of McElhone. Meanwhile, Davis is giving another kind of performance as Gordon. She guards her reasons for wanting to eradicate the visitors closely. She never elaborates, and she keeps her visitor a secret. It’s enough to see Davis’ frightened expression and know that she doesn’t trust Solaris—she feels it’s manipulating them. “We are in a situation that defies morality,” she explains, trying to convince Chris to destroy the visitors and return to Earth. Elsewhere, the general twitchiness of Davies recalls his character in Ravenous (1999), especially during the scene where Chris and Gordon discover his secret.

The presentation evokes Tarkovsky’s film in its close-knit interior scenes, but more often Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) in its display of science-fiction objects: a rotating space station, geometrical shots of a shuttle docking, the spare interiors, the planet itself. Although Soderberg uses CGI to complete his effects, his modest uses have resulted in visuals that remain convincing—entracing even. The hypnotic, pulsating surface of the planet glows with bioluminescent light, its appearance echoing a spectral view of the Sun. Voluminous flares reach out from the planet, while steady currents of pink, blue, and purple light writhe on the surface. Shooting as his other pseudonym, cinematographer Peter Andrews, Soderberg’s visual approach relies on placing Solaris in the middle of the frame, while human characters seem to be just off-center. His aesthetic is subtle, resisting flashy camerawork and, as always, with a contemplative tone. The approach extends into the unassuming production design by Philip Messina, a regular collaborator with Soderbergh in the early 2000s, as well as the sound design. Notice the low hum of the space station beneath every scene, which always reminds us that we’re in a vacuum, millions of miles away from Earth.

Along with the mesmeric electronic score by Cliff Martinez, many aspects of Solaris look and feel like a Soderbergh production. Trying to pin down what that means has been a challenge for many critics and scholars. He can seem like a chameleon, changing to suit the material. In the years since the film’s release, the director has tried a number of genre experiments: a World War II drama in black and white, a political biopic, a sprawling plague epic, a Hitchcockian thriller, an action film, and a social drama with male strippers. And despite his willingness to broaden his horizons, a distinct formalism and atmosphere emerge from Soderbergh’s films—they are both present and not present in Solaris because the material demands more rumination and dissection than a typical commercial release. Soderbergh’s use of memory images, for example, might be interpreted as flashbacks. Instead, consider their uses as part of an ongoing conversation between Chris, his unconscious mind, and Solaris that embraces the non-literal associations made through montage. Soderbergh intercuts between the three during Chris’ particularly metaphysical fever dream sequence, showing the depth of his obsession and guilt, and each cut implies their symbiotic relationship. But the film never resists the origins of the genre, as demonstrated by the tense finale that finds Solaris increasing in mass, the station with low fuel, and escape vital.

Soderbergh’s ending to Solaris draws from both the genre and Lem’s ethereal connections between the mind and the physical world, encapsulated by Chris and Rheya’s recitation of Dylan Thomas’ poem “And death shall have no dominion.” The final trick, where Chris seemingly avoids disaster and finds himself back on Earth, may seem ineffective at first, and this sequence’s awkward voiceover does little to support the otherwise consistent formal approach throughout the film. But as it turns out, the passage—and perhaps even the voiceover—is another illusion of Solaris; it’s also a formal twist within a narrative one. Chris, haunted by the idea that he remembered Rheya wrong, resolves to stay. “I love you,” Rheya tells him. “I wish we just could live inside that feeling forever. Maybe there’s a place where we can. But I know it’s not on Earth.” As they embrace in the frightening final images of the station disappearing beneath the surface of Solaris, they are no longer alive or dead. They’re living in their love. It’s a strangely emotional and optimistic ending, albeit haunting and thought-provoking. Some may attempt to figure out what we’ve just seen, how it works out logically and scientifically, but Soderbergh has provided all the information necessary to arrive at a satisfying conclusion. Like the scientists trying to understand the intentions of the planet below, Soderbergh delivers the same internal experience for his viewers, which must be solved through introspection. His film amounts to a rare, absorbing science-fiction tale that uses its actors, deceptively modest formal approach, and genre to sublime effect.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review