Snowpiercer

By Brian Eggert |

Inside a mobile dystopia running across the icy wasteland of Earth, the inhabitants of the “Rattling Train” or Snowpiercer live in a class-segmented microcosm of human society. The planet has been frozen and uninhabitable ever since a plan to prevent further global warming went horribly wrong, when world powers released the chemical CW7 into the atmosphere and incited a new ice age by mistake. What’s left of the human race rides on this high-speed train. Originally built by an eccentric futurist as a sustainable, ever-mobile ecosystem of amenities galore, now this perpetual motion machine keeps out the sub-zero cold and keeps humans in, with nowhere else to go. The privileged few live in luxury cars toward the head of the train, while squalor and hunger run rampant at the grimy tail end. By design, any attempted revolt in the rear cars is separated from the front, and these bloody uprisings serve only to thin out the numbers in the lower classes. Indeed, all the worst social and political atrocities conceived by the human race have been locked up in a series of train cars in Snowpiercer, an ambitious and visionary film.

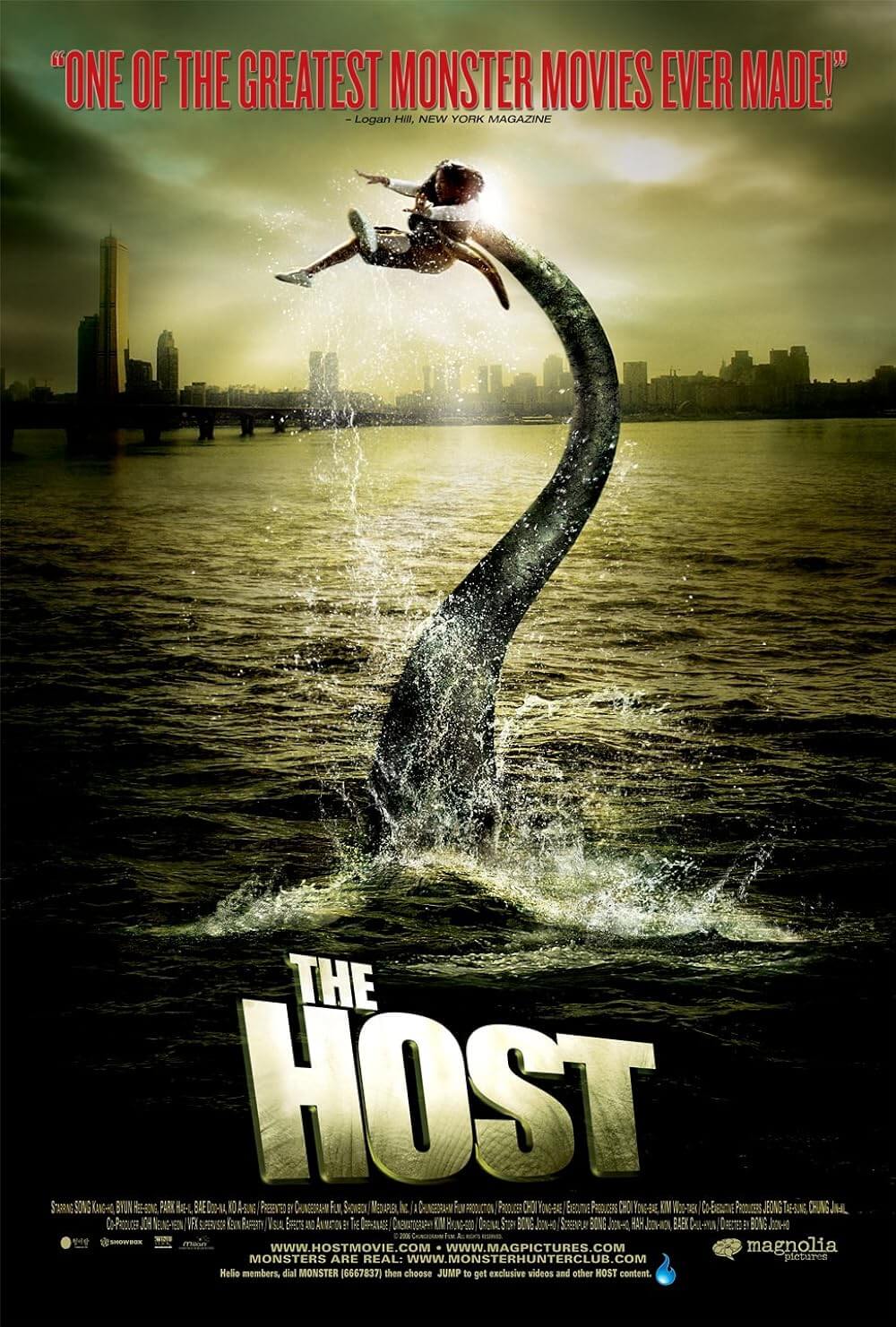

Based on the French graphic novel series Le Transperceneige from 1982 (authored by Jacques Lob, Benjamin Legrand, and Jean-Marc Rochette), Snowpiercer marks the first English-language production from Bong Joon-ho, the South Korean director behind box-office champs The Host (2006) and Memories of Murder (2003). Bong and Kelly Masterson (Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead) adapted the material and primary investors at CJ Entertainment developed the $40 million independent production outside of Hollywood, a rarity for an epic science-fiction tale featuring an all-star cast, among them Captain America himself, Chris Evans, and S. Korean star Song Kang-ho. Snowpiercer opened internationally in 2013 through various companies, but U.S. distributors at The Weinstein Company fought with Bong over which cut would be released stateside. And while Bong was victorious in fending off Harvey Weinstein’s demands that the director cut 20 minutes of footage to better suit U.S. audiences, the film’s debut was truncated to a limited release as Bong refused to compromise his art.

Given what made it to the screen, Bong’s clash with the Weinsteins and even the film’s limited release were well worth it. The director has achieved something every bit as innovative and supremely polished as the works of Christopher Nolan or James Cameron, and each moment feels integral, measured, and carefully realized to his uniquely dark, yet comic, sensibilities. As the squalid masses in the caboose fight their way to the “sacred engine” in the film, the closest comparison belongs to the BioShock series of the gaming realm, in that each section of the icebound train offers a new, increasingly disturbing environment and series of obstacles for our heroes in rear passenger cars to overcome, all of it designed as a utopia by its billionaire-industrialist maker. Of course, all utopias are ultimately dystopias, and this nightmarish locomotive is no exception. To be sure, Wilford (Ed Harris), the train’s unseen designer presiding at the frontmost car, is worshiped like a god but has more in common with the Wizard of Oz.

Given what made it to the screen, Bong’s clash with the Weinsteins and even the film’s limited release were well worth it. The director has achieved something every bit as innovative and supremely polished as the works of Christopher Nolan or James Cameron, and each moment feels integral, measured, and carefully realized to his uniquely dark, yet comic, sensibilities. As the squalid masses in the caboose fight their way to the “sacred engine” in the film, the closest comparison belongs to the BioShock series of the gaming realm, in that each section of the icebound train offers a new, increasingly disturbing environment and series of obstacles for our heroes in rear passenger cars to overcome, all of it designed as a utopia by its billionaire-industrialist maker. Of course, all utopias are ultimately dystopias, and this nightmarish locomotive is no exception. To be sure, Wilford (Ed Harris), the train’s unseen designer presiding at the frontmost car, is worshiped like a god but has more in common with the Wizard of Oz.

After brief explanatory titles in the opening, Bong thrusts us into his train’s Dickensian rear compartments, where plans for a rebellion have already begun to form. Seventeen years have passed since the world froze over, and various people tried raids and failed to overthrow the Powers That Be, none of them getting more than a few cars forward. But the rear-class leader, no doubt deliberately named Gilliam (John Hurt), has received encoded messages in their food supply—slimy-looking protein bars made out of… well, you’ll just have to see. The messages suggest the train’s security designer, currently detained in the morgue-like prison car, can engineer their way passed the security doors. Gilliam relies on a leader-in-the-making, Curtis (Evans, in his best performance yet), and his young protégé, Edgar (Jamie Bell) to guide the revolt. But even as the plan commences, we get a taste of this twisted world when comically fascistic spokesperson Mason (Tilda Swinton, behind grotesque dentures and a thick Yorkshire accent) arrives with armed guards to oversee the seizure of several children. Two single parents, Tanya (Octavia Spencer) and Andrew (Ewen Bremmer), are forced to watch as their younglings are torn away for Wilford’s yet-unknown plans.

Once the rear passengers launch their attack and begin to move forward from their grayed-out monochrome world, they see colors they’ve never seen; some of them have never looked outside at the white-covered landscape of skeletal buildings sealed in ice (a world animated by admittedly just-serviceable CGI, nothing spectacular). Many have struggled to survive so long that they’ve never thought to ask where their food or water comes from. When they reach the prison car, they find Minsu (Song), the security designer, and his daughter Yona (Ko Ah-sung, who also played Song’s daughter in The Host). The former, irascible, self-preserving engineer speaks only Korean and must communicate through a translator box; the latter is more cooperative and uses her telepathic abilities to help Curtis’ mission. Both Minsu and Yona are drug addicts and agree to help in exchange for Kronole, an industrial waste byproduct sniffed like super-glue for a high. With Song and Ko, the film’s well-rounded international cast never ceases to impress, however playful their characterizations, from Spencer’s lively mother role to Romanian actor Vlad Ivanov, who plays Wilford’s most dangerous henchman.

Once the rear passengers launch their attack and begin to move forward from their grayed-out monochrome world, they see colors they’ve never seen; some of them have never looked outside at the white-covered landscape of skeletal buildings sealed in ice (a world animated by admittedly just-serviceable CGI, nothing spectacular). Many have struggled to survive so long that they’ve never thought to ask where their food or water comes from. When they reach the prison car, they find Minsu (Song), the security designer, and his daughter Yona (Ko Ah-sung, who also played Song’s daughter in The Host). The former, irascible, self-preserving engineer speaks only Korean and must communicate through a translator box; the latter is more cooperative and uses her telepathic abilities to help Curtis’ mission. Both Minsu and Yona are drug addicts and agree to help in exchange for Kronole, an industrial waste byproduct sniffed like super-glue for a high. With Song and Ko, the film’s well-rounded international cast never ceases to impress, however playful their characterizations, from Spencer’s lively mother role to Romanian actor Vlad Ivanov, who plays Wilford’s most dangerous henchman.

Meanwhile, Curtis struggles to accept himself as a leader, and when we learn why in a late scene during an equally heart-rending and horrifying monologue by Evans, everything about what came before is enhanced tenfold. In a similar way, Bong’s vivid uses of violence and gristly, unforgiving imagery (both real and imagined)—specifically those concerning cannibalism and a number of shocking deaths—take far more risks than a Hollywood production would have. But the death and violence serve a very specific purpose once all is revealed and we meet the man behind the curtain. Those familiar with Bong’s earlier films, or those of Snowpiercer‘s co-producer (director Park Chan-wook of Oldboy infamy), will anticipate a particularly merciless, nihilistic attitude toward death, whereas a major studio would’ve never allowed so many notable characters and familiar faces to lose their lives. Bong also injects pitch-black humor into the proceedings with a pointedly S. Korean finesse that will challenge some viewers; the style compares to something like the expressive, ultra-violent works of Paul Verhoeven (RoboCop, Total Recall).

In spite of the bloodshed, Bong evokes Terry Gilliam’s Brazil and 12 Monkeys through Snowpiercer‘s broad post-apocalyptic imagination and mischievous aesthetic details, which have been labored over and leave everything onscreen completely engrossing. The train itself, built on a series of rotating soundstages, deserves the highest regard as an accomplishment in production design by Ondrej Nekvasil (The Illusionist, 2006). Each car has a distinct look and believable space, such as the most grisly sequence in the film when security doors open to reveal dozens of Wilford’s soldiers armed with axes and blunt instruments, leading to a bloody battle that soon goes dark when the train enters a tunnel. A later car was evidently modeled after The Shining‘s Overlook Hotel, complete with the posh upper-crust looking ghostlike and Al Bowlly singing “Midnight the Stars and You” on the soundtrack. But the most frightening car must be the elementary school, overseen by Alison Pill’s eerily enthusiastic schoolmarm, a sharp and cheery contrast to what came before, and invariably touched with an undercurrent of something sinister.

For any kind of meaningful finale, Curtis needs not only to command the train but stop it; however symbolic it may be to “take the engine,” it’s not enough to occupy and maintain the train’s carefully sustained life cycle. Curtis wants answers, and there are no easy answers or resolutions to be had. Stopping the train means certain death and perhaps a narrative resolution that flows against what U.S. audiences have grown accustomed to in their romantic Hollywood productions. But Bong’s last few films each have an ending that defies standard commercial expectations, and Snowpiercer too attempts to tie up several thematic and narrative strains within a few brief scenes at the end—in part by becoming overtly symbolic and even self-reflexive once we meet Wilford in the flesh, who’s all-too-aware of the ironies and symbolism of his creation. Still, the film juggles these ideas into a philosophically gratifying conclusion pregnant with meanings that reflect capitalistic societies and, to a greater extent, the unfortunate patterns of the human race.

For any kind of meaningful finale, Curtis needs not only to command the train but stop it; however symbolic it may be to “take the engine,” it’s not enough to occupy and maintain the train’s carefully sustained life cycle. Curtis wants answers, and there are no easy answers or resolutions to be had. Stopping the train means certain death and perhaps a narrative resolution that flows against what U.S. audiences have grown accustomed to in their romantic Hollywood productions. But Bong’s last few films each have an ending that defies standard commercial expectations, and Snowpiercer too attempts to tie up several thematic and narrative strains within a few brief scenes at the end—in part by becoming overtly symbolic and even self-reflexive once we meet Wilford in the flesh, who’s all-too-aware of the ironies and symbolism of his creation. Still, the film juggles these ideas into a philosophically gratifying conclusion pregnant with meanings that reflect capitalistic societies and, to a greater extent, the unfortunate patterns of the human race.

Like every Gilliam film, Snowpiercer should be seen at least twice: once to absorb the film’s intricate details and grow accustomed to the director’s wonderfully outlandish style, and another to consider the sometimes unsubtle ways in which the film seeks to subvert various authorities (politics, gods, and even nature) through the course of the narrative. It’s a disturbing and fascinating world that Bong has created, realized through impeccable craftsmanship and verisimilitude, and always nuanced character-building. High-concept science-fiction outside of the Hollywood studio system has rarely, if ever, been so visionary and accomplished. Had Snowpiercer been released in a larger format, the film could have been a major breakthrough for Bong; instead, its following will surely develop over time as the right audiences discover it and spread positive word-of-mouth. And a few years from now, everyone will wonder why The Weinstein Co. resolved to sweep the film under the carpet, as it becomes a cult hit and hopefully more. Thoughtful, provocative, and far more enjoyable than your average blockbuster, Snowpiercer‘s pure entertainment value is outmatched only by its sobering commentary on the continual inhumanity of the human race.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review