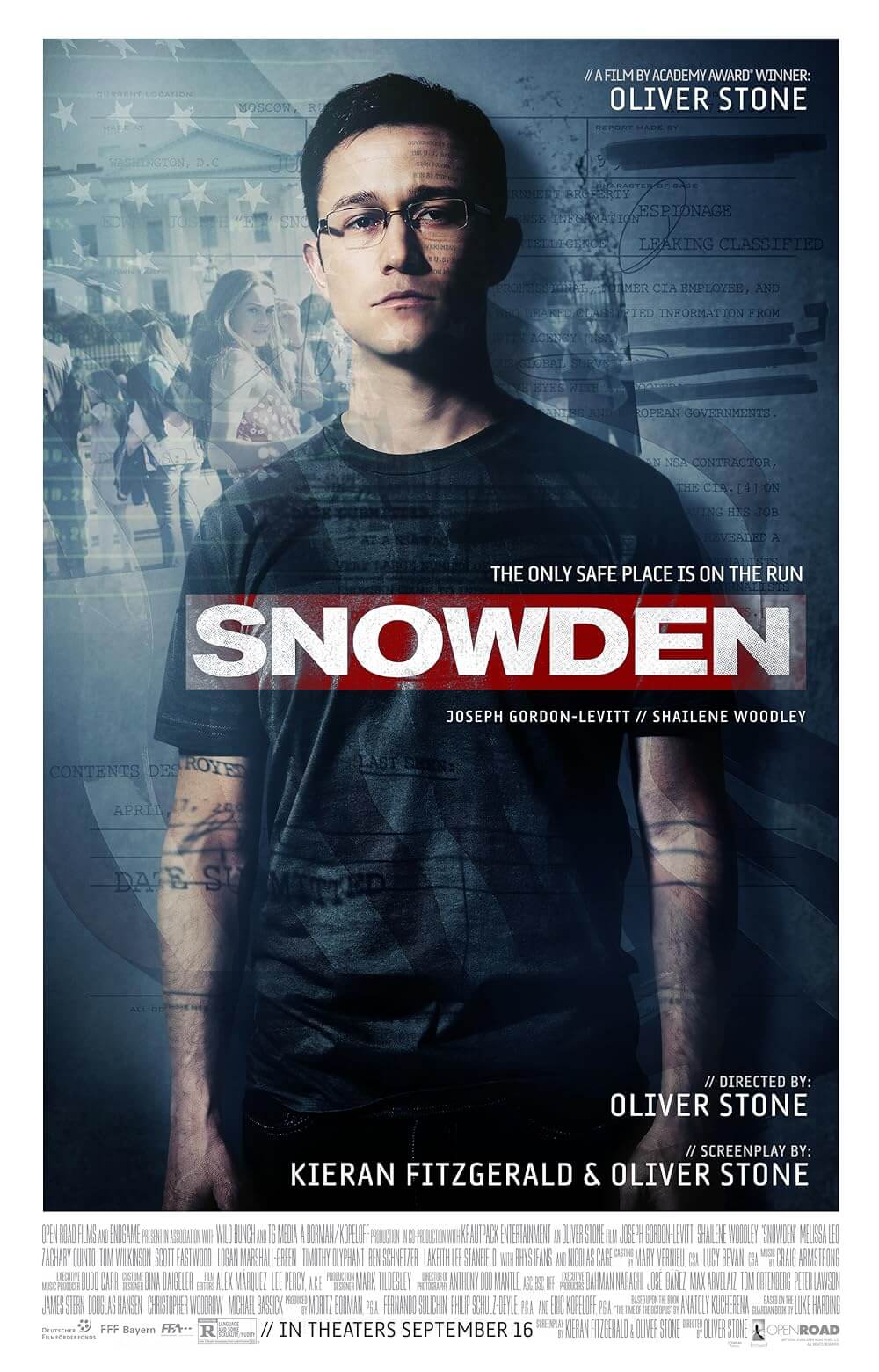

Snowden

By Brian Eggert |

Oliver Stone’s filmography includes several films about individuals who have an unshakable love for America; that is, until they learn more about their country and feel compelled to speak out against its injustices. He won two Oscars for directing pictures about young men who lose their innocence fighting in Vietnam. In Platoon (1986), Charlie Sheen’s character witnesses how U.S. soldiers become monstrous killers, and for what purpose he does not know. Tom Cruise starred as Ron Kovic in Born on the Fourth of July (1988), a paralyzed veteran who goes from a die-hard right-winger preaching “Love it or leave it” to becoming an anti-war figurehead. In his best film, JFK (1991), Stone follows Kevin Costner’s patriotic New Orleans District Attorney as he uncovers a conspiracy to eliminate the President to support the military industrial complex, thus destroying any ideals he held about his country. The examples go on and on, and the director’s long series of disillusioned idealists continues in Snowden.

Stone’s film about the former CIA and National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden returns him to the kind of material that made him an icon of political controversy and artistic provocation. In the last two decades, Stone’s output has softened from his radical days that seemed to tap into the cultural and sociopolitical consciousness of all Americans. Titles like the troubled Alexander (2004)—for which the director has released three or four subsequent cuts on home video—or the mawkish World Trade Center (2006) seem like the safe, squeaky clean products of another director. On the other hand, material that could have resulted in another of his contentious milestones, such as W. (2008) or Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps (2010), feels too even-tempered and seems to have had all teeth extracted. With Snowden, Stone at least postures himself behind the divisive figure, and the result is his best film since the 1990s.

Whether you label Snowden a traitor or patriot, Stone’s film gives you much to consider. It doesn’t leave you feeling enraged as some of Stone’s earlier films might have, but it also doesn’t allow a dismissive response. Stone and his co-writer Kieran Fitzgerald based their screen story and factual details on Luke Harding’s book The Snowden Files, as well as Time of the Octopus, written by Snowden’s Russian lawyer Anatoly Kucherena. The director also met with Snowden several times over the course of the production, beginning in 2014. Being close to the material, and the man, Stone wants to portray Snowden as the modest, rational, and steady guy he seems to be—at least based on what we see of him in Citizenfour (2014), Laura Poitras’ Oscar-winning documentary about Snowden.

In many ways, Stone’s film could be viewed as a companion piece to Citizenfour, adding his tried-and-true romantic humanism to the dense factual intent of Poitras’ doc. The director has earned criticisms for placing too much theatrical emphasis in his otherwise politically charged films. But then, he’s working in drama, the purpose of which is to engage on a primarily emotional plane of understanding (if you want cold hard facts, seek out one of his own documentaries or his 10-part series on Showtime, The Untold History of the United States). His depiction of Snowden, portrayed with eerily accurate vocal intoning by Joseph Gordon-Levitt, catalogs the gradual deterioration of Snowden’s idealistic love of America and trust in its government, and all the personal implications that result from his decision to take action.

Snowden’s story begins in 2004 when he volunteers for the U.S. Army Reserve in response to 9/11. He’s a conservative who loves his country and wants to defend it, and he’s shattered when an injury leaves him incapable of being a soldier. Given his smarts, he applies to the CIA, where he’s engaged by Corbin O’Brian (Rhys Ifans), a steely recruiter who hires Snowden because he’s a gifted computer scientist, not because he would make a good spy (Snowden cites Star Wars among his personal philosophies and states it would be “cool” to have top security clearance). Reserved and in some cases socially awkward, Snowden isn’t required to be a charismatic spy in the Cold War tradition; rather, he will be preventing hackers from the United States’ future cyber enemies, China and Russia. Meanwhile, Snowden hesitates with his artsy girlfriend, Lindsay Mills (Shailene Woodley), because she dares question the Bush administration and the invasion of Iraq.

The film cross-cuts between Snowden’s progressing career in the CIA and his fateful 2013 interview with journalists from The Guardian (Tom Wilkinson, Zachary Quinto) and documentarian Poitras (Melissa Leo). Set in a Hong Kong hotel room under paranoid fear that U.S. authorities could burst through the door at any moment, the scenes between Snowden and his interviewers have a desperate sense of impending justice, as they wait for the London paper to publish Snowden’s story. Having seen what the CIA does to whistleblowers, Snowden wants to avoid a drumhead trial and jail time; he would prefer a fair jury trial, which he knows he won’t get. A few years earlier, Snowden befriends a terminally dissatisfied CIA instructor (Nicolas Cage) who’s been constrained to a desk job for his own idealism. Snowden doesn’t yet realize how much the two are alike, until he begins to grasp the extent to which his government is monitoring, well, everyone.

Gordon-Levitt’s performance is perhaps the best thing about Snowden. He captures a pared manner, articulated with a monotone voice and a coolly composed presence. Though he may be a tech nerd, Snowden restrains his passions save for a few crucial moments, and otherwise carries himself as a logical, thoughtful individual who can tolerate an unbelievable amount of pressure—he often fidgets with a Rubik’s Cube, an essential component to the story, to keep his hands busy. His relationship with Lindsay remains essential to the film’s drama, as he’s unable to talk about his classified job or top secret missions in Geneva or Japan. They begin as fundamental opposites, but gradually, over the course of the film, he begins to understand why Lindsay remains suspicious of the government and, in due course, is not suspicious enough.

Scenes exposing the scope of the U.S. government’s moral, ethical, and legal cyber-crimes against world citizens contain a frightening veracity (further explored in the recent doc, Zero Days). Consider Snowden’s sudden insistence that Lindsay cover her laptop’s camera, or how he demands his reporter friends put their smartphones in the microwave. Earlier, we see why: his CIA associates can access a personal computer with a few clicks and watch or listen to anyone they want, all without the need for a warrant or any reasonable legal authority. The film outlines Snowden’s fear that by the time the government surveilles the second, third, or four-tier contacts of a target, they’re gathering data on millions of people, specifically Americans more than any other nationality. Snowden’s desire to act and expose these practices finally comes when his personal life is invaded—a moment with unsettling implications.

Stone’s desire to remind his audience how these events remain an essential discussion also leads to some of his most clumsy artistic choices. Whereas Snowden’s dramaturgy guides us through the proceedings with urgent moral trepidation, the ending sets aside the film’s narrative to showcase Edward Snowden himself, which in turn removes the viewer from the film’s story and drops us into reality. Of course, this tactic hopes to remind audiences that, at any moment, the U.S. government could be watching, and how what Snowden did still effects us today—despite ensuing laws that do little to prevent such widespread data mining. Relevancy aside, the ending quashes a wholly satisfying dramatic closure; then again, closure isn’t really a possibility with this story, given how Snowden’s story remains unfinished. To this day, Snowden and Mills remain in Moscow, exiled.

Formally, Stone’s film looks straightforward, far removed from the whirlwind blaze of his earlier pictures like JFK, Natural Born Killers (1993), or even Any Given Sunday (1999). The lensing by Anthony Dod Mantle (127 Hours, Slumdog Millionaire) presents a composed, digital sheen, while the film’s overall tenor seems respectful and subdued. As a result, many critics have said Snowden isn’t paranoid enough, but the film’s subject is less about the violations of privacy employed by the U.S. government and more about Snowden himself. The two concepts remain inextricably connected, of course, but Stone’s primary method of generating empathy is his humanist perspective, which remains compelling throughout this very effective piece of filmmaking. By the last scenes, the film accomplishes what it set out to do: Stone brings to light that our disturbed and anxious feelings about cyber-scrutiny are not paranoia, because that word suggests the menace isn’t real. Snowden’s deeply selfless act remains the brave work of a disillusioned idealist whose rebellion has made him a criminal to some, a hero to others.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review