Smile 2

By Brian Eggert |

Rinse, recycle, repeat. That’s writer-director Parker Finn’s approach to Smile 2, the sequel to his 2022 hit. Paramount Pictures couldn’t resist fast-tracking another one after the original earned $217 million at the box office on a $17 million budget. Finn delivers precisely that—just another one about a monster that passes from person to person through witnessed trauma. The victim is then “systemically infected, possessed, and murdered by some metaphysical being,” as one character explains in a moment that feels written for the trailer. With the entity intent on driving the protagonist to the brink with hallucinations—often in the form of people with a sinister smile—the movie deploys a familiar array of maddening situations that find Naomi Scott’s character losing her grip on reality. Thanks to Finn’s evident formal control and a much larger budget, Smile 2 may not deepen its predecessor’s mythology but reproduces the same material with confidence and potent results. And much like the first one, the sequel delivers a few chilling and memorably gory scenes wrapped in an atmosphere of relentless dread and paranoia.

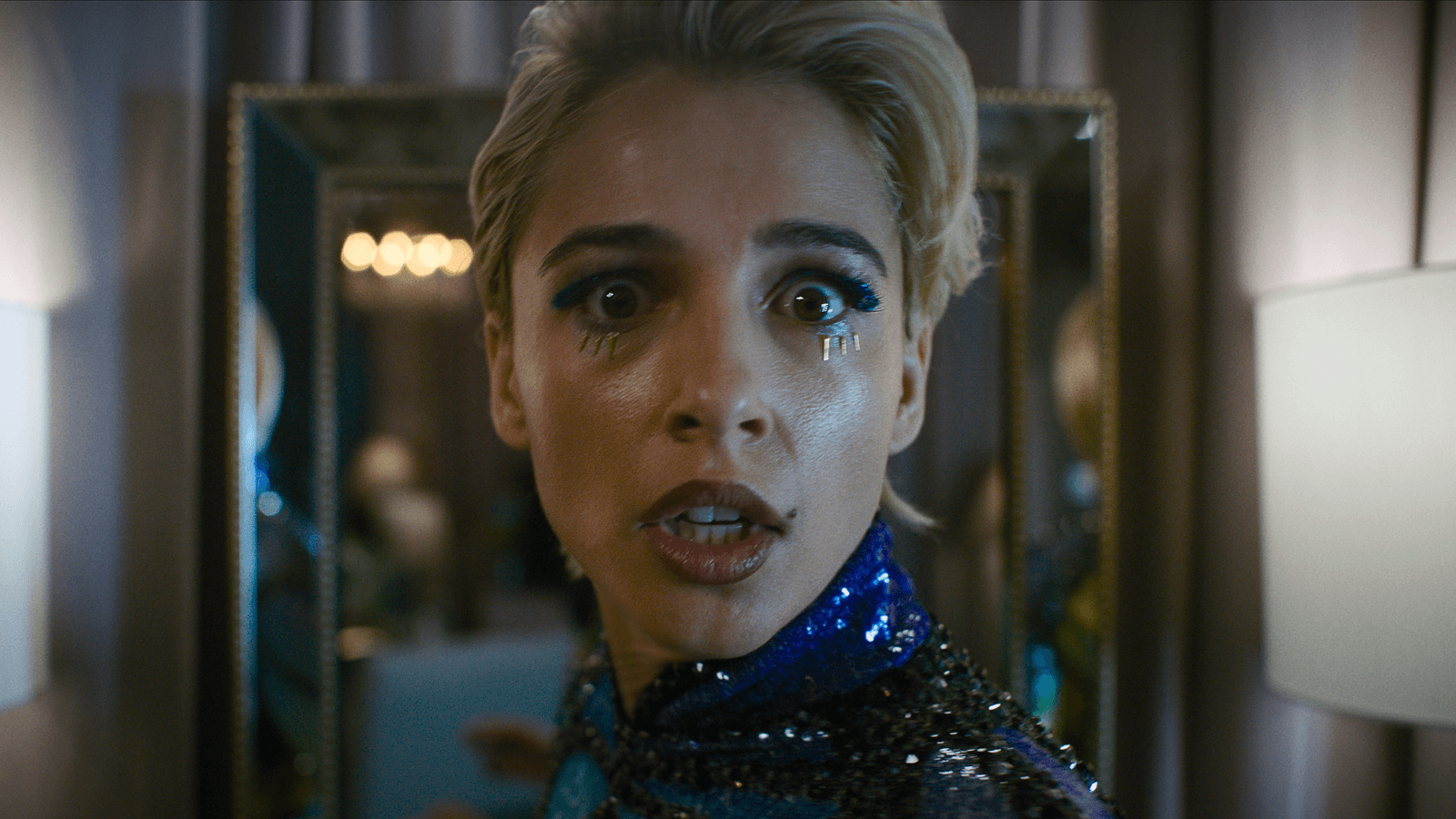

After a quick and visceral prologue that closes a chapter on the previous movie’s sole surviving character (Kyle Gallner), Smile 2 picks up with Grammy-winning pop star Skye Riley (Naomi Scott). A recovering addict, Skye struggles with her disease, which, a year ago, led to a traumatic car accident, a lengthy recovery, prolonged guilt over her past behavior, and a career shake-up. When we meet her, Skye is barely holding it together, if not borderline unhinged with a mild case of trichotillomania (pulling her hair out from anxiety). Yet, Skye’s oppressive manager-mother (Rosemarie DeWitt) has encouraged her to start a new tour. Still reeling from a back injury obtained during the accident, one night, Skye sets out to score some Vicodin from an old friend, Lewis (Lukas Gage), who recently witnessed some trauma and came down with a case of “metaphysical being.” Inevitably, Lewis’ grisly death passes the force onto Skye, and, as expected, it exploits her pre-existing issues to make her increasingly erratic, uneasy, and dangerous.

Finn’s screenplay is repetitive, but then, isn’t that true of most horror sequels that give audiences more of the same with each new installment? Holding that aspect over Smile 2 would be blind to how past franchises have thrived on repeating their successes. However, Finn adds to that original-to-sequel repetitiveness with his narrative structure, which winds itself around and around for the feels-long runtime of 127 minutes. Skye experiences a recurring series of creepy and messed-up hallucinations, and each one follows an identical pattern: Skye notices something strange and feels dread. The threat amplifies, leading to a shocker moment or aural jump-scare, at which point the situation reveals itself to be a delusion. Given Skye’s frantic reaction, everyone around her suspects that she’s either using again or having a nervous breakdown. If this setup occurs too often, the specifics prove effectively creepy. Take a freaky apparition where her background dancers, all sporting that unnerving downcast smile, make moves toward her in choreography from the dark side of Bob Fosse’s mind.

Scott’s performance is excellent and larger-than-life, which feels appropriate for this material. Her character goes to pieces, and it’s tantamount to watching Gena Rowlands unravel in A Woman Under the Influence (1974). Finn has smartly written Skye with several symptoms and quirks that could serve as a case study in trauma-related emotional dysregulation. She’s so filled with complexes and neuroses that you wonder how anyone thought she should be performing again—not to mention how she managed to write, record, and release a new album; plan a whole tour; and heal from her injuries all within the first year after her accident. Regardless, her therapist has told her to drink water whenever she needs a reminder of her fragile state, so Skye regularly downs whole bottles of Voss, and each bottle, each gulp, becomes more frenzied and representative of her mental state than the last. For others, Skye’s every outburst becomes further evidence that she’s losing it, making her claims about something supernatural sound questionable. And while spending time with Skye’s frayed mind can be a chore, it’s an implosion that’s difficult to watch but impressive for Scott’s commitment.

Smile 2 feels redundant, with so many fake outs that we soon distrust everything we see. That could be frustrating for viewers but it’s smart on Finn’s part; it puts us in Skye’s headspace, where the world before us cannot be trusted and slowly drives us mad. It also sets a horrifying precedent that manipulates the viewer into squirming in anticipation over what we know will happen. However recurrent it may be, it’s consistently scary and often shocking despite itself. Finn, who adopts the same fastidious, uncanny style as Longlegs director Osgood Perkins, teams with cinematographer Charlie Sarroff to deliver swiveling camera movements and upside-down angles to remind us that much of Smile 2 takes place in a distorted version of reality. The film’s jarring imagery is accompanied by deafening blasts on Cristobal Tapia de Veer’s score to produce an unavoidable and inevitable jump scare (a cheap if effective trick). But it’s the smaller moments, such as one where Skye struggles to forcibly pull out an IV, that made me squirm the most. Best of all, and quite dissimilar from Perkins, Finn embeds a sense of humor and levity beneath the terror that crops up unexpectedly—often courtesy of Dylan Gelula, who plays Skye’s estranged best friend.

The sequel’s use of a distressed pop star, and even some of Lester Cohen’s production design, cannot help but bring Brady Corbet’s Vox Lux (2018) to mind. But the comparison is mostly superficial, with Corbet’s film being an investigation of celebrity and Finn’s film being a metaphor for recovery, post-traumatic stress disorder, and maladaptive guilt. But like Vox Lux, Smile 2 boasts some convincing concert stages, flashy costumes, and original music (complete with catchy songs about tragedy and having a broken mind). However, if the primary function of the sequel is to scare audiences with a spookily fun time, then Finn achieves what he set out to accomplish. No matter how repetitive and familiar the sequel is when placed next to the first entry, it’s consistently scary and frequently disturbing. If nothing else, it proves that, sometimes, being a good copy can have the same result as the original.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review