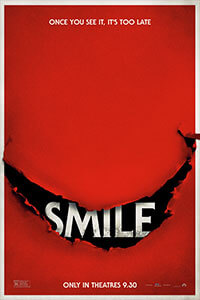

Smile

By Brian Eggert |

Writer-director Parker Finn’s Smile does what many good horror films do: it twists something pleasant into a source of terror. Take Stephen King, who has spent much of his career turning things we love into frightening distortions, from Saint Bernards in Cujo (1981) to clowns in It (1986) to antique shops in Needful Things (1991). In Finn’s debut feature, the title’s welcoming and contagious gesture becomes the source of an unseen evil entity that spreads trauma from one victim to the next (“hurt people hurt people” might be the movie’s motto). The fundamentally absurd premise is sold thanks to the filmmaker’s expert control of his schematic presentation, with haunting sound design, a disorienting score by Cristobal Tapia de Veer, and a steady visual treatment that feels crafted by an intentional artist. Best of all, Sosie Bacon leads the movie and delivers a performance that requires her to come apart before our eyes. If you allow Smile to work you over as intended, you will feel unnerved and justifiably haunted by the final shot.

In the cold open, the overworked Dr. Rose Cutter (Bacon) sees one last patient at the end of her shift at the emergency psychiatric hospital—a place decorated in pink pastels like an Easter nightmare. She meets Laura (Caitlin Stasey), who, panicked, claims to be haunted by something evil. Laura says it wears people’s faces like masks, even people she knows, “Only it’s not a person.” A moment later, Laura sees the entity in the assessment room (we do not), and she slashes herself from the left side of her face down across her throat—all while flashing a Kubrick smile. Later, the shot over her corpse in the morgue reveals that blood has soaked through the sheet in a distorted grin shape. The incident cannot help but leave Rose shaken, so much so that, not long after, she begins to see what Laura described: strangers with the same smile, horrific dreams from her past, and apparitions of Laura. When her administrator (Kal Penn) tells her to take a week off to recover, she uses that time to investigate what happened to Laura and what’s happening to her.

Finn and cinematographer Charlie Sarroff approach Smile with a controlled formalism that evokes Alfred Hitchcock by way of James Wan. Their bird’s-eye-view and upside-down angles convey an other-worldly element at play, but most shots remain close within Rose’s subjectivity. Instead of showing the viewer what Laura saw before her suicide, Finn offers Rose’s perspective, and she sees only a disturbed patient whose mind is manifesting terrible things. By that same formal logic, we soon see the haunting figures that appear to Rose but no one else. Finn and editor Elliot Greenberg stage scenes that unfold as vignettes of masterfully sustained tension and disbelief, including a false security alarm, a missing cat, a traumatic birthday party for her nephew, and strained encounters with a manic patient. In each case, Rose sees something that others do not. Since her fiancé (Jessie T. Usher) and amusingly domesticated sister and brother-in-law (Gillian Zinser, Nick Arapoglou) refuse to listen to her claims that something supernatural is happening to her, she meets with her own therapist (Robin Weigert), who diagnoses Rose with unresolved trauma.

An elevated horror buzzword, “trauma” has become the default theme for self-serious horror. Whereas Ari Aster had the good sense to not openly discuss his theme in therapeutic sessions for his characters in Hereditary (2018) and Midsommar (2019), films like this year’s requel Scream and Smile make trauma a topic the characters openly discuss at length. While the Psychology 101 discourse becomes a tad too obvious, it nonetheless deepens Rose’s backstory and provides Bacon a chance to display her range. The film’s first scene shows a preadolescent Rose discovering her mother dead from an apparent overdose of drugs and alcohol. Her therapist claims these lingering feelings have caused stress and compelled her current manifestations. Such details mean Bacon must spend the entire film emotionally fried by her past and terrified by present circumstances, and she portrays every scene marvelously—to the extent that, for the first half, we entertain the possibility that Smile might be about the overworked, under-rested Rose’s trauma-induced delusions.

An elevated horror buzzword, “trauma” has become the default theme for self-serious horror. Whereas Ari Aster had the good sense to not openly discuss his theme in therapeutic sessions for his characters in Hereditary (2018) and Midsommar (2019), films like this year’s requel Scream and Smile make trauma a topic the characters openly discuss at length. While the Psychology 101 discourse becomes a tad too obvious, it nonetheless deepens Rose’s backstory and provides Bacon a chance to display her range. The film’s first scene shows a preadolescent Rose discovering her mother dead from an apparent overdose of drugs and alcohol. Her therapist claims these lingering feelings have caused stress and compelled her current manifestations. Such details mean Bacon must spend the entire film emotionally fried by her past and terrified by present circumstances, and she portrays every scene marvelously—to the extent that, for the first half, we entertain the possibility that Smile might be about the overworked, under-rested Rose’s trauma-induced delusions.

But soon enough, the terror kicks into high gear. Rose discovers that Laura witnessed her professor bludgeon himself to death with a hammer while wearing the same smile; before that, the professor also witnessed a suicide. Upon investigation, with the help of her ex-boyfriend (Kyle Gallner)—a detective, conveniently enough—Rose uncovers a contagion of suicides that goes back a long way. In each case, the victim has four to seven days before they kill themselves. As Rose’s mission becomes one of stopping the cycle, the genre-savvy viewer may catch whiffs of horror classics. Note the hints of Ringu (1998) and It Follows (2014) in Finn’s treatment of invisible monsters, countdowns, and curses. Late in the protracted climax, one thinks of A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), when Rose must use the power of her mind and imagination to overcome her tormentor. Without the movie making any direct references or overt visual nods, it’s evident that Finn knows the genre and has been inspired by it.

Some moviegoers will refuse to meet Smile on its terms and dismiss the central concept as silly. At a certain point in my screening, a portion of the audience turned on the movie and chuckled through it. Others, I sensed, had been caught in Finn’s spell. Count me among them. If the last third begins to drag, with Rose realizing she’s in a hallucination a few too many times, Finn and Bacon manage to create a convincing character whose fraught emotional state remains in the foreground of an otherwise preposterous idea. When Rose starts using some of the same language that Laura used in the beginning, Finn resists underlining the fact and allows Bacon’s performance to guide us through the moment. Whatever quibbles one might find in the overreliance on trauma as a surface-level theme and saggy 115-minute runtime, Smile is a confidently directed and acted film that demonstrates a clear vision. It’s the kind of debut that should make horror fans excited about what Finn does next.

(Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this review listed the release year of Ringu as 2008. This has been corrected to 1998.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review