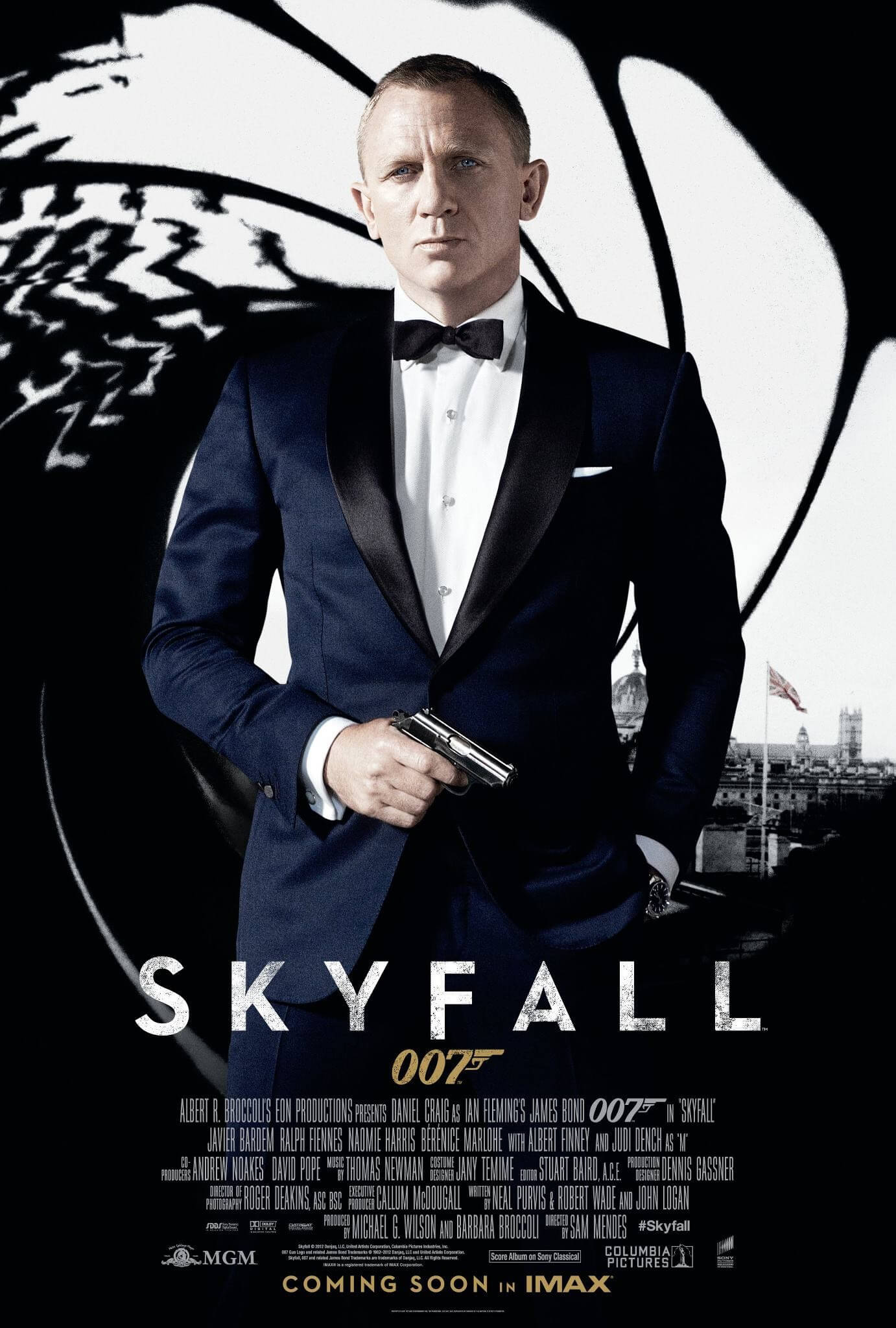

Skyfall

By Brian Eggert |

Following the decades-old formula established in twenty-two other James Bond films, the twenty-third entry, succinctly named Skyfall, reinvigorates the franchise’s customary recipe with cinematic elegance and a sense of dramatic gravity. How fortuitous then that the recent, protracted sale of the James Bond series distributors MGM incidentally delayed the film long enough, so its release coincided with the 50th anniversary of Dr. No in 1962, Ian Fleming’s first 007 novel adapted into a non-spoof film. Indeed, many of Skyfall’s narrative themes revolve around embracing tradition but also shaking up the establishment to make way for the future, whereas director Sam Mendes also incorporates a recurring visual theme of reflectivity to emphasize how the Then and Now support one another. Though, in another filmmaker’s hands, the same story could have been just a stale rehash of old ideas and familiar action sequences, Mendes’ knowing stylistic flourishes and his regal treatment of the material prove an aged franchise is still capable of entertaining us in familiar ways without feeling outdated.

The screenplay by Neal Purvis, Robert Wade, and John Logan lovingly follows the standard formula established by classic Bond pictures. Take these plot points, all surely familiar: 1) There’s another kaleidoscopic title sequence (with a song by Adele) featuring naked female silhouettes and small weaponry in a retro video collage; 2) Daniel Craig’s third appearance as Bond, after the most recent disappointment Quantum of Solace, is pitted against a villain with unique physical maladies. (One wonders why MI6 doesn’t just monitor everyone with horrible facial scars.); 3) Bond beds a villainess henchwoman only to have her die, again; while he also beds the resident, much less interesting good girl (Naomie Harris); 4) There are impressive chases, shootouts, and explosions. All standard turns. But this common actionized superspy setup comes with the same underpinned seriousness celebrated in the franchise’s 2006 reboot, Casino Royale. Nothing about the brooding atmosphere of Craig’s debut as 007 felt routine for this series, and although Skyfall’s basic outline is quite routine, the film is set apart by the significance with which these elements are handled, and also what occurs between the broad strokes.

In the opening sequence, shot in Turkey, Craig’s Bond pursues a hired gun (Olga Rapace) who’s stolen a top-secret list containing the names and secret identities of undercover agents spying on terrorist organizations. If it gets out, dozens of deep-cover agents will be exposed. At the end of a breathless chase (on car, motorcycle, and backhoe-upon-train), Bond is struck by an unintended bullet fired after M’s (Judi Dench) rash order, and he falls into a river, seemingly dead. Of course, he doesn’t die; he escapes to a beach resort to enjoy anonymity, drowning himself in drink and sorrows and women. Meanwhile, M’s career is under scrutiny for allowing MI6’s biggest security breach in British Secret Service history. It only gets worse when their office is blown to smithereens in a strategic attack. Who’s behind it all? Bond returns home to get answers, but the new branch head (Ralph Fiennes) has reservations about 007’s return. Passing the reentrance exams only because M has fixed the numbers, our hero is sent out to find the hired gun from Turkey, who leads him to the evil mastermind—a sadistic megalomaniacal super-hacker named, Silva (Javier Bardem). Both Bond and Silva have in common deeply personal resentments against M, who has shaped them both through good and bad decisions in her past. The story plays out with Silva on a blood hunt for M, and the dutiful Bond wincing through bad memories as he protects her.

In the opening sequence, shot in Turkey, Craig’s Bond pursues a hired gun (Olga Rapace) who’s stolen a top-secret list containing the names and secret identities of undercover agents spying on terrorist organizations. If it gets out, dozens of deep-cover agents will be exposed. At the end of a breathless chase (on car, motorcycle, and backhoe-upon-train), Bond is struck by an unintended bullet fired after M’s (Judi Dench) rash order, and he falls into a river, seemingly dead. Of course, he doesn’t die; he escapes to a beach resort to enjoy anonymity, drowning himself in drink and sorrows and women. Meanwhile, M’s career is under scrutiny for allowing MI6’s biggest security breach in British Secret Service history. It only gets worse when their office is blown to smithereens in a strategic attack. Who’s behind it all? Bond returns home to get answers, but the new branch head (Ralph Fiennes) has reservations about 007’s return. Passing the reentrance exams only because M has fixed the numbers, our hero is sent out to find the hired gun from Turkey, who leads him to the evil mastermind—a sadistic megalomaniacal super-hacker named, Silva (Javier Bardem). Both Bond and Silva have in common deeply personal resentments against M, who has shaped them both through good and bad decisions in her past. The story plays out with Silva on a blood hunt for M, and the dutiful Bond wincing through bad memories as he protects her.

Bardem’s portrayal as the menacing, blonde-haired, monologuing madman outshines an ensemble that offers otherwise terrific performances. From his first appearance, where he challenges Bond’s sexual identity by making an aggressive homoerotic pass, to later scenes behind a Hannibal Lecter glass cage where he reveals his damaged history, Bardem renders Silva into one of the best, most intimidating, most unforgettable entries in the James Bond rogues gallery. It’s an Oscar-caliber performance from an actor capable of instilling horror, humor, and depth into a creepy role. On the flipside is Craig, grim-faced and dark, whose stubble has been peppered with gray. We learn more about this Bond’s past and why Craig’s rendition remains an unstable “damaged goods” presence, which reinforces the film’s temporal themes of past and future. Then again, Craig’s gravitas is counteracted by Skyfall’s one major failing—it’s re-embrace of another Bond-ism: comic one-liners. Silly quips and flirtations and sexual puns galore litter the script, some successful and others not. Though necessary to pay full homage to the classic Bond formula, it’s an aspect of the franchise that has never charmed this critic.

What must be noted is how unlikely Mendes and his crew seem for a James Bond picture, and why their presence makes Skyfall something great. A helmer of often emotionally devastating and challenging drama such as Jarhead and Revolutionary Road, Mendes has never made an action movie; but his manners behind the camera lend the proceedings dramatic weight in every scene, as though there’s something more to every character. There’s no black-and-white comic book heroism or villainy here. The film takes place in a gray area. In conveying as much, Mendes and editor Stuart Baird linger on their shots and resist the now-standard frenetic cutting style of action movies, allowing the audience to fully absorb the gorgeous cinematography by Roger Deakins. Deakins, too, is an unlikely choice for an actioner. Having shot nearly every Coen Brothers film—and, among his best work, the grave Western The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford—Deakins has an incredible eye for composition and creating textures with light. There are shots in Skyfall’s enthralling finale of a house burning on a Scottish moor at night, the flames illuminating the thick fog and setting the atmosphere ablaze. It’s stunning. Deakins also resists shaky-cam and composes beautifully framed action scenes that are thrilling yet easy to follow.

Globetrotting as James Bond films often do, Skyfall makes fantastic use of each locale and incorporates each with sly influence from classic cinema. During an interlude in Shanghai, Bond enters a dark room filled with glass walls and doors, all lit from the glowing and reflecting false images projected from the neon signs outside the building, not unlike the famous hall of mirrors sequence in Welles’ The Lady from Shanghai (1947). In the film’s finale at the aforementioned Scottish manor—another intimate, unlikely choice, replacing the climactic assault on the villain’s lair of most Bond films—Bond finds himself scarcely armed and defending his territory from Silva’s oncoming goon attack, recalling Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971). It should also be noted that the Scottish house attack begins with Silva riding a helicopter that sounds music at its imminent victims, straight out of Apocalypse Now (1979). The helicopter later destroys Bond’s coveted car, the same Aston Martin DBS from Goldfinger (1964) and Thunderball (1965), a moment that stirs up a particularly enraged scowl from Craig.

Globetrotting as James Bond films often do, Skyfall makes fantastic use of each locale and incorporates each with sly influence from classic cinema. During an interlude in Shanghai, Bond enters a dark room filled with glass walls and doors, all lit from the glowing and reflecting false images projected from the neon signs outside the building, not unlike the famous hall of mirrors sequence in Welles’ The Lady from Shanghai (1947). In the film’s finale at the aforementioned Scottish manor—another intimate, unlikely choice, replacing the climactic assault on the villain’s lair of most Bond films—Bond finds himself scarcely armed and defending his territory from Silva’s oncoming goon attack, recalling Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971). It should also be noted that the Scottish house attack begins with Silva riding a helicopter that sounds music at its imminent victims, straight out of Apocalypse Now (1979). The helicopter later destroys Bond’s coveted car, the same Aston Martin DBS from Goldfinger (1964) and Thunderball (1965), a moment that stirs up a particularly enraged scowl from Craig.

Whereas Casino Royale was something completely and wonderfully different, and Quantum of Solace was little more than a lackadaisical sequel to Casino Royale, the ambitious Skyfall is, in a way, more significant than its predecessors in that it doesn’t require alterations to the typical formula to make it a resounding success. The film embraces the 007 blueprint, reintroducing coveted characters such as Moneypenny and Ben Wishaw’s Q, and even improves upon those traditions through its expert treatment. This is a film not presented in 3D, but there are multiple dimensions for moviegoers to savor. The quality of the production, its pristine lensing, carefully considered action sequences, and the layers behind the characters and storytelling make it a rich action movie experience and among the best entries in the James Bond legacy. Perhaps most important is how, thematically, it reminds audiences that, despite a healthy serving of both ups and downs over the years, this 50-year-old franchise remains something that can still, on rare occasion, surprise us.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review