Skincare

By Brian Eggert |

Skincare belongs to a subgenre of films about people who will do anything to become rich and famous. These films usually involve an ingénue or outsider trying to break into Hollywood, such as All About Eve and Sunset Blvd. in 1950, or more recently, Mulholland Drive (2001), Maps to the Stars (2014), and Babylon (2022). But there’s a seedier contingent where the fame sought proves lower level, which amplifies the stakes and makes the situation even more desperate and pathetic, yet also more human. Films such as Boogie Nights (1997) and The Bling Ring (2013) show their characters going to ridiculous lengths for a modicum of attention. Among this category of films about personal compromises and fragile egos, Skincare most closely resembles To Die For (1995), featuring Nicole Kidman as a suburban woman whose dream of becoming a news anchor leads to manipulation and murder. However, she justifies her behavior and choices with a twisted internal logic that she finds perfectly reasonable. Here, Elizabeth Banks plays a similar role—a self-proclaimed victim whose behavior suggests some seriously warped rationalizations.

A “fictional story inspired by true events,” the film draws from the sordid tale of Dawn DaLuise, who ran a small but thriving facial and waxing studio in West Hollywood, with clientele ranging from Jennifer Aniston to Hillary Clinton. In 2014, the 55-year-old aesthetician began receiving lewd texts and disturbing, stalker-y videos on her phone. Then, someone slashed her tires and posted false Craigslist ads with poorly Photoshopped pictures of her, offering all manner of sexual favors to anyone who responded. As the stranger-than-fiction tabloid story unfolded, much of what happened to DaLuise also happens to Banks’ character in the film. However, DaLuise’s story continues beyond where the film ends, with a complex legal trial and questions about culpability. Both in real life and the film, her response to these attacks blurs the line between victim and perpetrator. Such definitions remain ambiguous in Skincare, resisting any unequivocal statements about who’s the right or wronged party, though I cannot condone anyone’s behavior here.

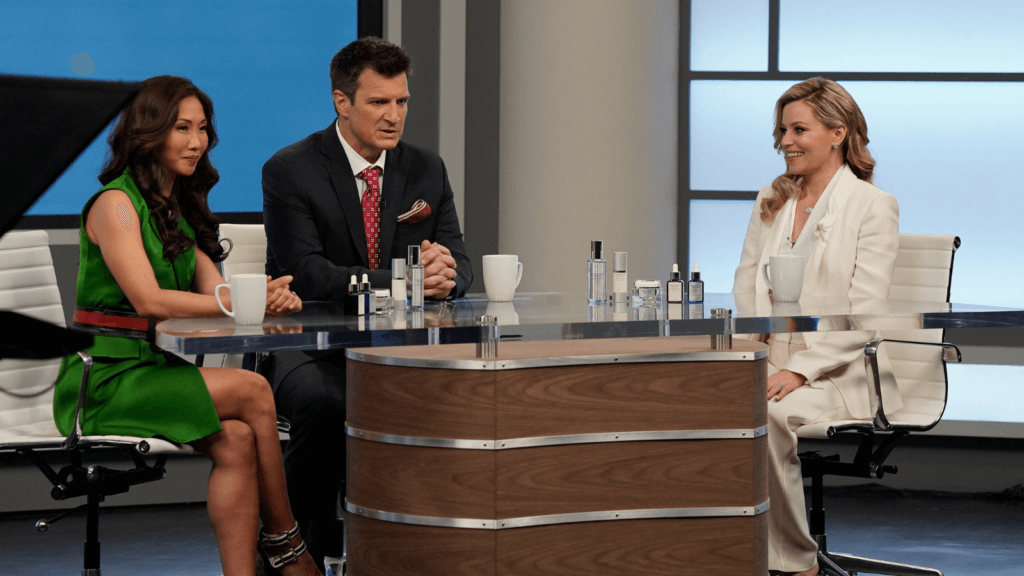

Directed by Austin Peters, the film opens in 2013, with the fictionalized version of DaLuise, named Hope Goldman (Banks), whose dreams for her business and celebrity are this close to becoming a reality. About to launch her first product line of lotions, oils, and serums, she records a television spot for a future episode of a popular Los Angeles morning show—the host (Nathan Fillion) of which will probably be a future #MeToo case. She boasts about her Italy-made products and attests, “I took everything I learned from 20 years in this business and bottled it.” Once the line launches, she can finally pay her increasingly impatient landlord (John Billingsley) his back rent. But just as she’s about to pop, a competitor opens a similar skincare shop nearby. Called “Shimmer by Angel” and boasting some NASA technology, the confident yet barbed proprietor, Angel (Luis Gerardo Méndez), begins to attract Hope’s clients after someone hacks into her email and sends out a troubling message, shaking their trust in her.

The situation escalates, threatening to ruin Hope’s well-laid plans. She desperately tries to hold everything together, but she suspects Angel has masterminded what’s happening to her. In response, she enlists the help of a twitchy life coach, Jordan (Lewis Pullman), whom she met through a client (Wendie Malick), to solve her problems. The screenplay, credited to Peters, Sam Freilich, and Deering Regan, hews close to Hope, telling the story from her perspective. She sees herself as the victim, yet the writers show her behavior as casually manipulative. Although she seems generous, giving away samples and free facials, every choice she makes is selfish. For instance, she overlooks how much her devoted assistant, Mandy (Michaela Jaé Rodriguez), has put into the business. She also takes advantage of a nearby mechanic shop run by Armen (Erik Palladino), casually flirting with him in exchange for free auto work and storing her surplus inventory in his back office. Armen clearly wants their association to be romantic, too, and Hope strings him along.

The situation escalates, threatening to ruin Hope’s well-laid plans. She desperately tries to hold everything together, but she suspects Angel has masterminded what’s happening to her. In response, she enlists the help of a twitchy life coach, Jordan (Lewis Pullman), whom she met through a client (Wendie Malick), to solve her problems. The screenplay, credited to Peters, Sam Freilich, and Deering Regan, hews close to Hope, telling the story from her perspective. She sees herself as the victim, yet the writers show her behavior as casually manipulative. Although she seems generous, giving away samples and free facials, every choice she makes is selfish. For instance, she overlooks how much her devoted assistant, Mandy (Michaela Jaé Rodriguez), has put into the business. She also takes advantage of a nearby mechanic shop run by Armen (Erik Palladino), casually flirting with him in exchange for free auto work and storing her surplus inventory in his back office. Armen clearly wants their association to be romantic, too, and Hope strings him along.

Banks is excellent at portraying this disingenuous yet complex character who might register as an outright monster if it weren’t for the fact that someone actually is out to get her. But even amid Hope’s virtue signaling and performative good-naturedness, the character never lost me entirely. That’s partly due to the performance; Banks has rarely been better. But it’s also due to a more outright menace at work. On the periphery, Méndez brings a smug yet vulnerable energy to his small role, while Pullman shows that he’s increasingly one of the most exciting character actors working today. This is also a well-assembled film, with Christopher Ripley’s crisp digital cinematography following Hope with urgent energy from one crisis to the next. With a career in music videos and documentaries, Peters demonstrates his aptitude for an immersive and paranoid experience: part satire, part thriller, and part L.A. Noir. To be sure, the scenario reminded me of the Mickey Rooney vehicle Quicksand (1950), a classic noir in which an Average Joe makes one moral compromise after another until, well, the title explains it.

While Skincare supplies a wild true story, it’s surprising the filmmakers didn’t use the opportunity to confront the uglier aspects of the titular trade. They conveniently ignore the commonplace injections, surgeries, chemical peels, plasma treatments, and various other grotesqueries of celebrity skincare. The writers could have emphasized the link between lurid physical procedures, superficiality, and ego-driven behavior more, and exploring the physical reality of what Hope does may have added an icky layer to the proceedings. But even as it is, this film is an involving experience that asks, “What are you willing to do to get where you want to be?” This is a pulpy, engaging story about the drives and ambitions that bring out the worst in people. It’s all the more tragic, comical, and chilling for the desperation around its low stakes. Skincare acknowledges that everyone has their reasons, but sometimes those reasons are selfish and awful.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review