Reader's Choice

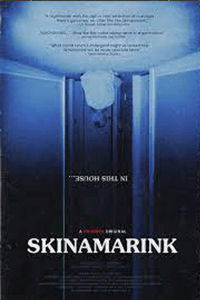

Skinamarink

By Brian Eggert |

Remember when you were very little and woke up in the middle of the night? And you searched in the dark for something familiar, arms outstretched, perhaps calling out for a parent. And every sound and light became exaggerated in the night’s emptiness, and the imagery of your most recent nightmare lingered in your half-asleep mind, reframing reality in disturbing ways. And though you probably only took a few steps or even sleepwalked, it felt like you had traversed a vast dreamscape fraught with terrors waiting to consume you. Skinamarink, named after the nursery rhyme, explores this singular concept. An experiment in analog horror, Canadian filmmaker Kyle Edward Ball crowdfunded his first feature into an intentionally paced and directed debut, released theatrically by IFC Midnight and the streamer Shudder. Although the minimalist film is admirably conceived and executed, the question is whether you have the patience for this sort of thing. The deliberate tempo and scarcity of narrative information may test your patience, as it did mine, even as you appreciate Ball’s evident skill, aesthetic confidence, and commitment to his conceptual intentions.

Set in 1995, the film doesn’t unfold like a standard horror movie but a half-conscious dream, entrenched in the perspectives of four-year-old Kevin (Lucas Paul) and his older sister Kaylee (Dali Rose Tetreault), whose faces seldom appear onscreen. After waking up one night, the children discover their parents have disappeared, and their house has been filled with a dreadful absence. They wander about in the dark, witnessing doors and windows vanish, only to see them reappear again. Lights flicker on and off, and the television glows with public-domain cartoons by Ub Iwerks and Max Fleischer. The children are seen mainly from the legs down, like humans in a Tom and Jerry cartoon, and their feet scamper on the carpet. Inaudibly whispering to each other, their voices sound muffled and, in some cases, appear subtitled. But then another voice arrives in the chasm of darkness—that of an unseen boogeyman who announces, “I want to play,” and later instructs Kaylee to “Look under the bed,” and “Close your eyes.”

Ball’s premise is the feature-length equivalent of the videos he produces on Bitesized Nightmares, his YouTube channel. There, commenters share their scary dreams, and he turns them into short films, running anywhere from 1-5 minutes long. Ball noticed a common theme among those who wrote out their experiences: Several people reported waking up and finding themselves in the dark, alone except for an unseen monster (a setup that sounds vaguely like the sleep paralysis demon explored in Rodney Ascher’s 2015 documentary The Nightmare). Exploring the idea to its limits, Ball shot Skinamarink for $15,000 in his childhood home, drawing from personal experiences and using his old toys for props. You get the sense that Ball has explored these hallways and rooms countless times before at night, and he instills a personal perspective that cannot be faked.

Shot on digital, Ball’s film maintains a formal agenda so rigorous that it might convince you there’s more happening than you can see. Skinamarink’s mise-en-scène replicates the appearance of film grain, giving the proceedings a visible texture that creates the illusion of movement. Scenes linger on a particular object or wall for what seems like an eternity, and the more you look, the more you convince yourself that something’s moving onscreen. Sometimes you’re right; other times, it’s just your imagination. As editor, Ball and his cinematographer Jamie McRae create long, unbroken shots, often placed near the ceiling or the ground. Much of the 100-minute runtime dwells on geometric compositions of walls, hallways, doors, and the floor, some of them so saturated in darkness that the brain requires a moment to process what you’re looking at. The imagery suggests a study of rectangles, like a filmic Rothko painting, and the appearance of any human figure becomes rare.

Shot on digital, Ball’s film maintains a formal agenda so rigorous that it might convince you there’s more happening than you can see. Skinamarink’s mise-en-scène replicates the appearance of film grain, giving the proceedings a visible texture that creates the illusion of movement. Scenes linger on a particular object or wall for what seems like an eternity, and the more you look, the more you convince yourself that something’s moving onscreen. Sometimes you’re right; other times, it’s just your imagination. As editor, Ball and his cinematographer Jamie McRae create long, unbroken shots, often placed near the ceiling or the ground. Much of the 100-minute runtime dwells on geometric compositions of walls, hallways, doors, and the floor, some of them so saturated in darkness that the brain requires a moment to process what you’re looking at. The imagery suggests a study of rectangles, like a filmic Rothko painting, and the appearance of any human figure becomes rare.

Behind these images is a vacuum-like omnipresence of white noise—a pervasive quiet that leads to the occasional jump-scare, signaled by a sharp audio cue, which, after so much silence and inactivity, cannot help but produce a jolt. Ball’s avant-garde presentation and minimalist approach to narrative leave the first hour or so almost devoid of progress. Kaylee and Kevin are barely characters, giving the film an ambiguous subjectivity that distances the viewer. Plus, there’s no telling what exactly happens over Skinamarink’s duration. Are they haunted by a supernatural entity? A pair of mischievous parents? Or does the viewer simply witness the half-asleep imagination of a four-year-old in the middle of the night? Then again, after we hear the father on the phone saying Kevin fell down the stairs early in the film, maybe everything to follow exists in Kevin’s concussed state. However you might interpret the film, Ball’s approach makes something like David Lynch’s Eraserhead (1977) look like an experimental film rich in character and story.

No one could blame viewers for feeling unable to connect to Skinamarink. Then again, some have already called the film one of the scariest they’ve ever seen. That predominantly online response came after the film leaked last year, and social media users reacted with predictable hyperbole. Unfortunately, the conceit barely has enough to sustain a 30-minute short, much less its 100-minute runtime. Aside from the occasional upside-down angle and object on the ceiling, the film is exceptionally slow, like watching security camera footage and waiting for something interesting to happen. Paranormal Activity (2009) took a similar approach, but that movie played like a rollercoaster ride by comparison. And while a few moments in the last twenty minutes prove jarring, they’re not enough to justify the overwhelming boredom generated by the first hour or so. It’s apparent that Ball is a talented filmmaker with control over his craft, and Skinamarink no doubt turned out just as he planned, but I struggled to maintain any interest beyond a cold appreciation for the director’s commitment.

(Note: This review was originally suggested on and posted to Patreon on February 10, 2023.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review