Sinners

By Brian Eggert |

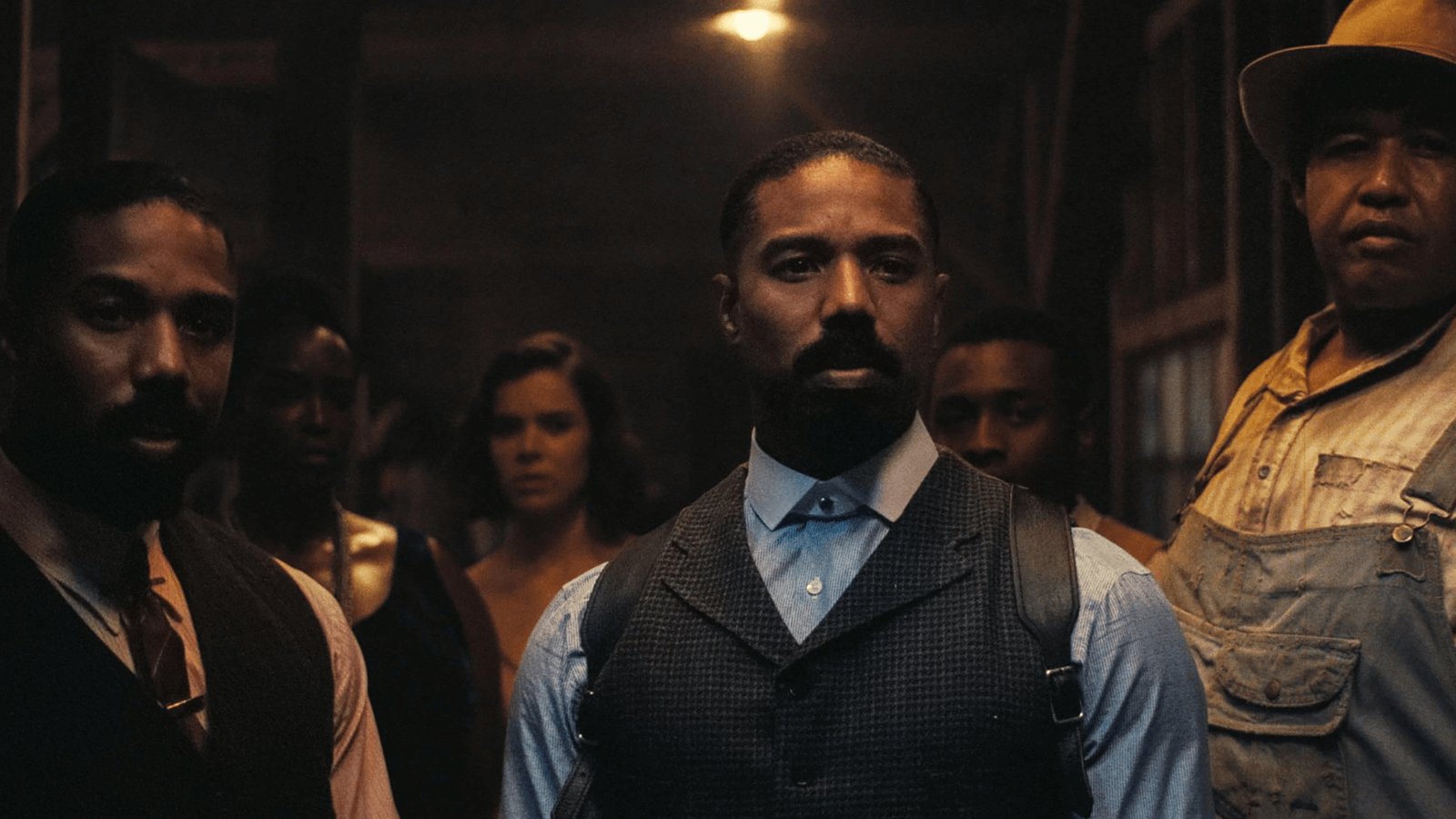

Sinners is a Trojan horse. On the surface, writer-director Ryan Coogler has acknowledged that he borrowed aspects of the scenario from Robert Rodriguez’s From Dusk Till Dawn (1996). Those familiar with the film will remember how it began as a thriller about two sibling convicts headed for Mexico, only to switch genres mid-story into a bloody vampire yarn. Similarly, Coogler’s story takes place in the Jim Crow South, following identical twin brothers, both played by Michael B. Jordan. The brothers start a juke joint and, just like Rodriguez’s movie, about halfway through, a creature of the night arrives to cause havoc—a secret the studio’s promotional department does not conceal in its marketing. The film is remarkable partly because it’s founded on patient character work, filmmaking bravura, and effective scares. Besides being an excellent vampire film, sure to please crowds, Coogler also sneaks in a potent and subversive commentary with provocative themes that, frankly, shocked, impressed, and delighted me—perhaps even more than his terrific execution of a vampire film. Sinners might be the most transgressive mainstream release by a major studio in 2025.

Coogler weaves his iconoclastic ideas into a popular milieu, disguising but never underplaying them. This is no surprise from the Black Panther (2018) director, who managed to comment on the history of colonialism, Black heritage, and racial oppression with an anticolonial revenge plot in a Marvel feature. Coogler’s perspective has been embedded into his films from the start with Fruitvale Station (2013), a remarkable debut about the police killing of Oscar Grant in 2009. From there, his career has come to resemble the trajectory of Christopher Nolan. Both filmmakers started with small, independently produced original features, followed by a period of masterminding major, distinct commercial successes for studios based on established intellectual properties. Both also finally earned enough clout with executives to develop original storytelling on a blockbuster-sized scale.

Sinners takes its time to build characters and give them dimension before Coogler turns his story on its head. The year is 1932 in Mississippi, and Sammie (Miles Caton), his clothes bloodied and face scratched as if by a claw, arrives at the church where his pastor father gives his Sunday sermon. Sammie’s father pleads with his brilliantly talented son to put down his prized guitar, the broken neck gripped in his hand. “You keep dancin’ with the devil, one day, he’s going to follow you home,” he’s told, accurately enough. A day earlier, ambitious and relentless brothers Smoke and Stack (Jordan) return to town after seven years to buy an old mill to establish a juke joint. This comes after fighting in the First World War, followed by a period of robberies, pimping, and working for organized crime bosses in Chicago. They purchase the building from the rotund Hogwood (David Maldonado), who promises no trouble from local factions. “The Klan doesn’t exist anymore,” he promises, prompting a collective eye roll from the audience and suspicions that remain unconfirmed until the cathartic finale.

Afterward, the twins organize “a real ring-a-ding-ding” for that Saturday night. It’s fueled by a stockpile of Irish beer and Italian wine in their truck, help from a husband-and-wife team of Chinese grocers (Li Jun Li, Yao), and music by Sammie and Delta Slim, an alcoholic blues man (Delroy Lindo, giving a performance that could earn him the Oscar he should have gotten for Da 5 Bloods, 2020). Coogler’s patience and the outstanding cast ensure no character feels one-note, including Stack’s former lover Mary (Hailee Steinfeld) and Annie (Wunmi Mosaku), a hoodoo conjurer whose fiery past romance with Smoke smolders again upon his return. Then, Coogler cuts to a man named Remmick (Jack O’Connell), who seems to drop in out of nowhere, sizzling like he’s fresh from the grill of a greasy spoon and pursued by a group of Choctaw men. Buzzards usher him to a small country house where a KKK couple, Joan and Bert (Lola Kirke, Peter Dreimanis), fall victim to Remmick’s bite. Before long, Remmick’s new trio arrives at the sweaty, sultry, joyous party thrown by Smoke and Stack, asking to be invited inside—a vamp calling card. When they eventually reveal their intentions, what follows is an intense bloodbath.

From a horror aficionado’s perspective, specifically concerning the vampire subgenre, Sinners ranks among the best ever made—the rare example of a genre effort that takes itself seriously as art. It belongs in the same conversation as Neil Jordan’s Interview with the Vampire (1994) and Byzantium (2011), Bill Gunn’s Ganja & Hess (1973), and Park Chan-wook’s Thirst (2009). Coogler is an evident fan, yet he creatively innovates and repurposes vampire motifs, such as Remmick adding knowledge and experience to a veritable hive mind with each new member he turns to his collective. This leads to the inevitable scene referencing The Thing (1982)—or, in keeping with the Rodriguez homage, The Faculty (1998)—where a few survivors munch on garlic to reveal who among them is a bloodsucker. Coogler’s vampires are vicious creatures who sing, dance, kill, and contort with nightmarish intensity. They loom in the shadows, their eyes glowing metallic red among the fireflies, before revealing the convincing practical makeup and vampire effects, from nasty bites to burning corpses.

This is what great storytelling looks like from both structural and formal perspectives. Working with cinematographer Autumn Durald Arkapaw, Coogler shot Sinners on 65 mm celluloid and printed it on 70 mm, giving the picture incredible detail and luminous colors. The visuals have the kind of textures only a photochemical process can deliver, with heavy shadows and earthy colors in the vivid scenes of dancing, erotic sex, and gory chaos. The palette evokes the past and never has the digital sheen of most movies in the 2020s. Some scenes, mostly the exteriors captured on various locations in Louisiana, were shot in an immersive IMAX frame, resulting in an aspect ratio that shifts or switches depending on the circumstances. For a climactic battle, the screen opens up, prompting the viewer to lean in with the expansion. Coogler’s approach to audio is just as engaging. More than once in the film, a character tells a story about a past trauma, and echoes of the incident play under the scene like a memory pressing on the back of the mind. Moreover, a haunting score by Ludwig Göransson and music performed by Caton, a genuine musical prodigy, ring out among the film’s many musical genres.

Like most technical aspects of Sinners, Coogler reinforces his themes with music. Sammie and Delta Slim play the blues, which the latter describes as the only true Black music, not something thrust upon them by the white community. Remmick and his vamp lackeys, too, sing harmonious but stringy Irish folk songs, such as “Wild Mountain Thyme,” to an impressed audience. When his fanged posse gathers in the night for an Irish vampire dance, it’s both impressive and unnerving enough to intimidate Michael Flatley. Elsewhere, inside Smoke and Stack’s nightspot, an inspired and wildly anachronistic sequence unfolds to Sammie’s music, which transcends time and sounds “so true it can pierce the veil between life and death.” Suddenly, amid this Southern Black community in the 1930s, performers, dances, and rhythms spanning hundreds of years play out in a layered audiovisual polyphony. It ranges from African tribal music to contemporary hip-hop to a ballet dancer—an overwhelming look at the evolution of Black music conjured by Sammie’s supernatural sound. The playfully dreamlike sequence soon finds everyone dancing amid the mill in fiery ashes, a symbol of the bliss art can bring even amid a devastated infrastructure.

Sinners is all the more potent given Warner Bros.’s decision to release it, after much reshuffling, on Easter weekend. It’s a confronting choice for a film that thumbs its nose at organized religion and links the methods of Christians to the groupthink mentality of Remmick’s vampires—even the collective mindset of the Ku Klux Klan. The central question in the film is whether Sammie will pursue his passion to play music or set aside his uncanny skill to follow in his pastor-father’s footsteps. More to the point: Coogler questions what, if anything, must be sacrificed to give the illusion of freedom and inclusion. Indeed, it’s tempting to join the open arms of organized religion or other such groups. But Remmick notes how they attempt to shape and mollify Black anger to their cause, despite not giving their community any real power or fellowship. However, Remmick’s offer of freedom is no less an indoctrination. More than once in the film, characters mention how white people “forced words upon us,” referring to Christian mythology and prayers. Remmick is an alternative, but no less rooted in conditioning; he converts people by stealing their lives and brainwashing them into his hive.

Coogler’s film warns against believing the hype of organizations, political groups, or religions proclaiming to champion freedom. One group’s definition of freedom often means the oppression of another group. This reality is playing out in the United States today, and it’s urgently present in Sinners without overstating the connection. Coogler argues that the only absolute freedom lies in that which you create, from works of art to the passion between two people. Sammie’s blues music becomes a key sound for Coogler because African Americans developed it in the years after the Civil War; it wasn’t part of a white cultural colonization as Christianity was. Almost as transgressive to his film’s remarks about organized religion (Christian or vampire), Coogler openly celebrates female pleasure, with a focus on oral sex, in several brief asides, suggesting a sly dig at certain religious and ultra-conservative groups that deem non-vaginal sex unnatural or, to use the title’s root word, sinful. In the film’s terms, our heroes are sinners because they play the music they want and have sex that feels good, especially for women.

Watching Sinners feels like an electric charge. It’s the kind of film that’s so assured, so well-executed, so thematically full, and so engaging that I was left with goosebumps. In the way only filmmakers such as Stanley Kubrick, Steven Spielberg, and Christopher Nolan have, Coogler takes an overdone genre and delivers a spectacle that’s a technical wonder and an intellectual gift. That’s been his unique skill since he first arrived on the scene over a decade ago, blending popular formats with topical issues and political engagement. Coogler ultimately walks the walk in the same way Sammie finds freedom through his music—not by adopting and repeating the lessons of some imperialist, colonizer, or religious proselytizer, but by creating something that feels unique to him. Even while delivering the requisite thrills and chills of a vampire yarn, Coogler’s passion, energy, and politics pulse through every frame of Sinners, one of 2025’s most entertaining and intelligent films.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review