Sinister

By Brian Eggert |

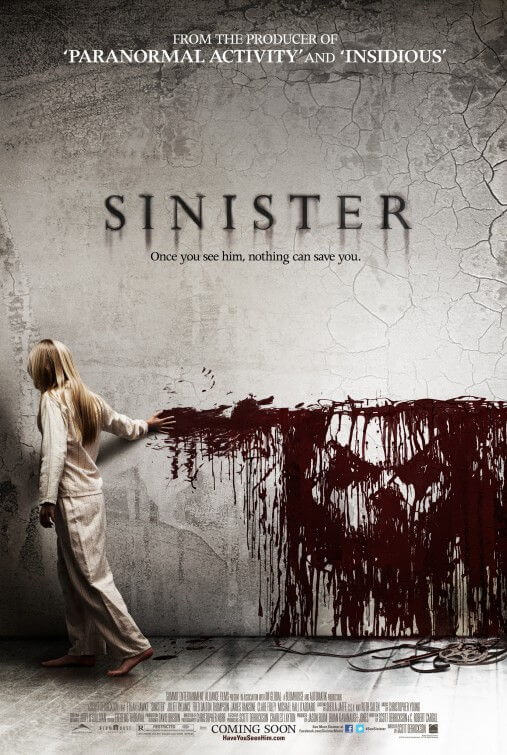

Hair-raising but not substantial enough to compensate for its downfalls, the slow-burning horror movie Sinister offers numerous eerie moments that effectively creep under the viewer’s skin; however, it’s bogged down by unfortunate genre clichés where characters go searching for Things That Go Bump In The Night and find little else except cheap “boo!” moments. Marketed as “from the producers of Paranormal Activity and Insidious,” the movie’s advertisements condense its setup well, being about found footage and an other-worldly clown-faced monster bent on taking children. But the protagonist, played by Ethan Hawke, spends too much time bumbling around in the dark to discover the origin of mysterious sounds, and not enough time heeding the obvious warning signs that foretell his doom. All the while, the filmmakers conjure up no end of false scares and marginal thrills, and in the end, the whole experience feels like a desperate effort to establish a memorable movie monster, if for no other reason than to ensure future sequels.

Hawke, best when he’s involved in indie productions, puts much into his paycheck role as Ellison Oswalt, a self-absorbed true crime author whose last major success was a decade ago. He’s desperate for another bestseller, so he moves his family—wife Tracy (Juliet Rylance) and their two youngsters, Trevor (Michael Hall D’Addario) and Ashley (Clare Foley)—into the small-town home where a family was murdered just months before. Hung from a tree in their backyard by an unknown killer, the victims’ daughter disappeared after the unsolved crime, and Ellison wants to find her and, in turn, become famous once more. Of course, Ellison doesn’t tell his wife they’ve moved into a murder site, providing the ammunition for a domestic blow up (and a fine scene of acting between Hawke and stage actress Rylance, who’s otherwise reduced to a cloyingly supportive wife role) later on. At any rate, things get scary when Ellison finds a box of old Super 8 films in their attic. On each, five in all, he finds whole families being murdered in various appalling ways (fire, drowning, lawnmower, etc.) by an unseen camera operator lurking outside the frame.

Who put these home movies in the attic? Well, the killer, obviously, but why? Ellison investigates further and, assisted by a quirkily quaint local deputy (James Ransone), he learns the families in the home movies are connected in ways he doesn’t fully understand, and his analysis shifts from the search for a missing girl to the discovery of a serial killer possibly active since the 1960s. Moreover, a curious occult symbol appears in each of these snuff films, and a local professor (Vincent D’Onofrio, appearing on webcam only) informs Ellison the symbol is linked with “Bagul” (pronounced “baa-ghoul”), an ancient pagan deity known for possessing and stealing children. We’re also told that Bagul is fed by the power of the images representing him, so whenever Ellison looks at another (not always inert) image of this demon-thing, he unintentionally sets into motion Bagul’s scheme. (Note: Given that Bagul is powered by visual reproductions, we can’t help but wonder which came first, the chicken or the egg?)

Scott Derrickson, director of The Exorcism of Emily Rose and the disastrous remake The Day the Earth Stood Still, employs an expert sound design team to layer the movie with cultish music and scratchy effects, most of which are non-diegetic and used unsparingly to unnerve the audience. There’s a spooky, grainy hum underneath suspenseful scenes that derives from a similar effect used in The Shining. Also borrowed from Kubrick’s film is Derrickson’s use of weird little children, the past victims of Bagul, who appear decayed and wraithlike with index fingers pressed against their lips, hushing about their predictable secrets. But as the movie progresses, the screenplay by Derrickson and C. Robert Cargill doesn’t follow its own rules, which becomes frustrating into the finale when everything goes south for Ellison and his family, yet in ways that leave us questioning the movie’s own logic given what happened earlier.

Sinister is at its best, and creepiest, in the scenes where Hawke’s character uncovers the mysteries of the family murders; once the story devolves into supernatural territory, all interest is lost. Since most of the story involves Ellison alone, in his office nervously watching and editing together scary snuff reels left by some supernatural demon, or wandering around his house at night chasing aural phantoms, the success of Sinister falls largely on Hawke. This actor is incredibly unnerved and reactive in his role, jolting and screaming in a tense, believable, surprisingly involved performance that’s contagious enough to make his audience jolt along with him. But he’s also playing a horror movie dope who doesn’t know when to pack up and leave the haunted house before it’s too late. (If you want to see Hawke in a better film like this, try this year’s The Woman in the Fifth.) And then there’s Bagul, a silly creature that looks like a rejected concept for the doll in Saw. However strong Hawke’s presence may be, the movie is best summed up by the titles referenced in its own marketing: Like the flaws of Paranormal Activity and Insidious, Sinister is left undone by its embrace of clichés, and an unsatisfying, rushed ending that cheapens everything good which came before.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review