Sing Sing

By Brian Eggert |

Note: This review was originally posted from the 43rd Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival on April 14, 2024. It has since been edited and expanded. The film arrives in theaters via A24 on July 12, 2024, and expands to Minnesota on August 16.

After learning a person has been incarcerated, people often react with fear, judgment, and condemnation toward the individual, even after their relationship with the justice system has ended. Compassion and forgiveness are much rarer responses. Sing Sing, a profoundly sensitive portrait of humanity finding an outlet and purpose through art, draws out feelings of empathy where society usually reserves little. Greg Kwedar’s new feature showcases the Rehabilitation Through the Arts (RTA) prison program that allows those inside to express themselves creatively and, in doing so, heal. The film was based on an Esquire article from 2005 titled “The Sing Sing Follies” by John H. Richardson and follows a group of inmates staging an original play, Breakin’ the Mummy’s Code, written by RTA facilitator Brent Buell. “Hope can set you free” is the famous tagline from The Shawshank Redemption (1994). And while the RTA provides hope and escape through self-expression, Sing Sing acknowledges the dehumanizing effect of imprisonment alongside the painful yet inspiring process of healing and personal redemption. But its sense that every incarcerated person deserves consideration as a dimensional human being makes the film a powerful reminder of what such programs hope to achieve.

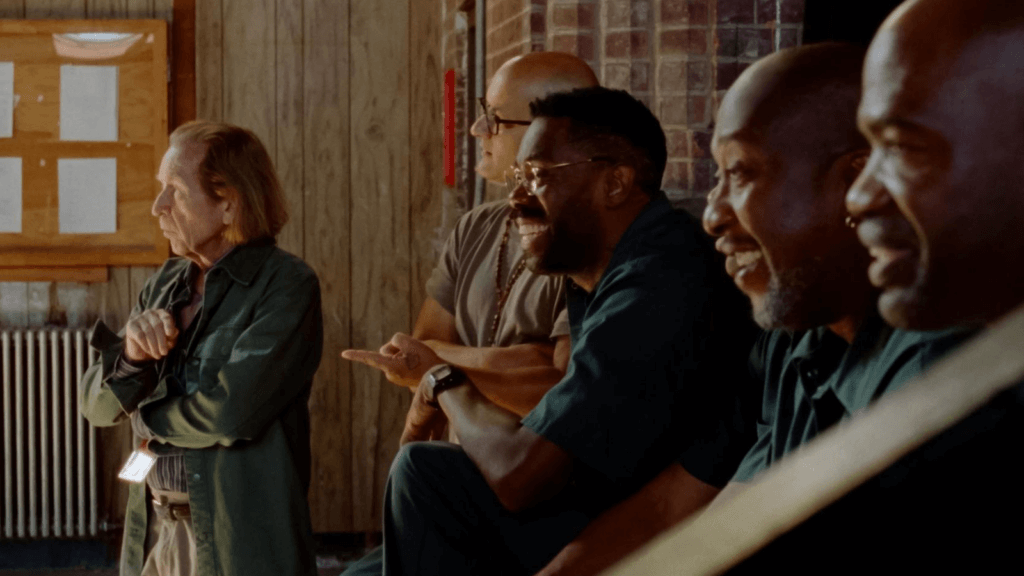

Countless films have been made about the redemptive and healing powers of art, often in the form of biographical portraits of famous artists, such as Pollock (2000), about Jackson Pollock working through his tumultuous life with abstract expressionism, or Frida (2002), about Frida Kahlo processing her psychological and physical wounds through her painting. Sing Sing offers a thicker slice of reality, served in a docu-drama style. Starring an ensemble that includes formerly incarcerated actors, some of whom were involved in Sing Sing’s RTA program, Kwedar’s film engages in what his co-writer Chris Bentley calls “community-based filmmaking” to tell the genuine stories—if slightly dramatized for effect—of those involved. Kwedar’s production took a similar approach to his last feature, 2021’s Jockey, by using actual locations and real-life contributors. Shooting in the decommissioned Downstate Correctional Facility in New York State, which closed in 2022, the director’s aesthetic, captured on celluloid with a single camera by cinematographer Pat Scolar, roams around prison spaces and intimately frames the lives on display, using a grainy, dusty-looking film stock and what appears to be natural light. The score by Bryce Dessner is so gentle and complementary that it hardly registers, even if it’s doing a lot of work to enhance the experience.

Central to the film is Colman Domingo, who plays John “Divine G” Whitfield, a creative who was wrongly convicted of a crime in the 1980s (the real Divine G has since been released). Divine G helps coordinate RTA productions at Sing Sing Correctional Facility in New York, alongside Buell (Paul Raci, in a role similar to his Oscar-nominated part in 2020’s Sound of Metal). Much of the narrative involves them mounting a production. The arrival of a new face complicates their plans. Clarence “Divine Eye” Maclin (playing himself), a former drug dealer, must acclimate to his new surroundings in the theater group, often challenging and questioning their methods. Apart from Domingo, Raci, and the memorable role of Mike Mike by Sean San José (Domingo’s longtime friend enlisted for the part), the performances throughout have a raw quality that loses none of their emotional power despite the occasional unpolished presence. Each of these men is earnest and often draws from actual experiences. The characters grapple with their situation and engage in drama therapy to work through their internal issues, some spilling out during rehearsals while also, extratextually, mingling with reality.

Though they often stick to the classics or something originated by Divine G, Buell writes their new production and weaves in imagery and ideas supplied by those in the program. It’s a bizarre blend of time travel, Shakespeare, and various genres in which cowboys, pharaohs, and gladiators share the stage with Hamlet and Freddy Krueger. By folding everyone’s influences into the play, each member has a personal stake and interest in contributing to the show’s success. And while it’s difficult to understand what Breakin’ the Mummy’s Code is about, the few details presented look outlandish and random, and it’s all the funnier and more entertaining as a result. Still, Divine G loses some of his much-needed control and ownership over the RTA production when Buell takes over writing duties and Divine Eye earns a more prominent role during the audition process—featured in a delightful montage that, like much of the film, was unscripted and dependent on improvisation and spontaneity.

Though they often stick to the classics or something originated by Divine G, Buell writes their new production and weaves in imagery and ideas supplied by those in the program. It’s a bizarre blend of time travel, Shakespeare, and various genres in which cowboys, pharaohs, and gladiators share the stage with Hamlet and Freddy Krueger. By folding everyone’s influences into the play, each member has a personal stake and interest in contributing to the show’s success. And while it’s difficult to understand what Breakin’ the Mummy’s Code is about, the few details presented look outlandish and random, and it’s all the funnier and more entertaining as a result. Still, Divine G loses some of his much-needed control and ownership over the RTA production when Buell takes over writing duties and Divine Eye earns a more prominent role during the audition process—featured in a delightful montage that, like much of the film, was unscripted and dependent on improvisation and spontaneity.

Regardless, Kwedar focuses on how Divine G and his colleagues maneuver their everyday reality in prison against their creative outlet. Group therapy sessions feature ruminations on their lives, happy memories, regrets, and preoccupations. The interpersonal dynamics among the members supply inherently dramatic external and internal conflict. Divine G is not immune to these concerns, even though he presents as a composed group member on the surface. His ongoing parole reviews remain a source of hope and crushing disappointment; he also helps Divine Eye prepare for his meeting with the parole board, which often leads to the most affecting moments of friendship and bonding between the two. But as Divine G admits in an aching confession, “Sometimes, it’s all a little too much on the heart,” which just about sums up the film. Above all, Domingo is marvelous here, proving he’s a capable leading man, if too often limited to supporting roles.

Although it never becomes preachy nor overstates a political agenda, Sing Sing conveys the underlying importance of such programs, emphasizing how they provide a mental reprieve from the harshness of prison and a reminder to those involved of their humanity. I saw the film at the Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival, where representatives from the Minnesota political community spoke about its local relevance before the screening. Attorney General Keith Ellison praised Minnesota’s RTA programs as part of humanist prison reform that emphasizes the “correctional” and rehabilitative aspect of correctional facilities. These programs reinforce both “accountability and creativity,” in Ellison’s words, reminding those persons convicted of a crime that they’re more than a mere “convict” or “criminal.” They’re members of society who can be reintegrated and, hopefully, return to a normal life. The speakers also highlighted the Minnesota Rehabilitation and Reinvestment Act, which helps reduce sentences by as much as half for incarcerated persons participating in the RTA program and demonstrates they can contribute to the culture at large, specifically through the arts.

As one character in the film describes it: “We’re here to become human again.” From that seemingly simple ambition, Sing Sing explores what it means to be human and the value of seeing oneself as human instead of something less-than. Watching the film through that lens imbued Sing Sing with even more social significance; however, some of how Kwedar and Bentley’s screenplay handles the dramaturgy and narrative structure proves maudlin instead of natural. There’s a leap in time in the end that registers as though Kwedar felt compelled to end Sing Sing on a crowd-pleasing note. And while undeniably effective (I was in tears), the moment felt somewhat disingenuous compared to the rest of the story, at least given how Kwedar presented it. In this, the compression of time for dramatic impact feels like a manipulative flourish in a film otherwise distinguished by its authenticity. But that shouldn’t diminish the film’s overwhelming emotional power, incredible performances, or moving human drama.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review