Sin City: A Dame to Kill For

By Brian Eggert |

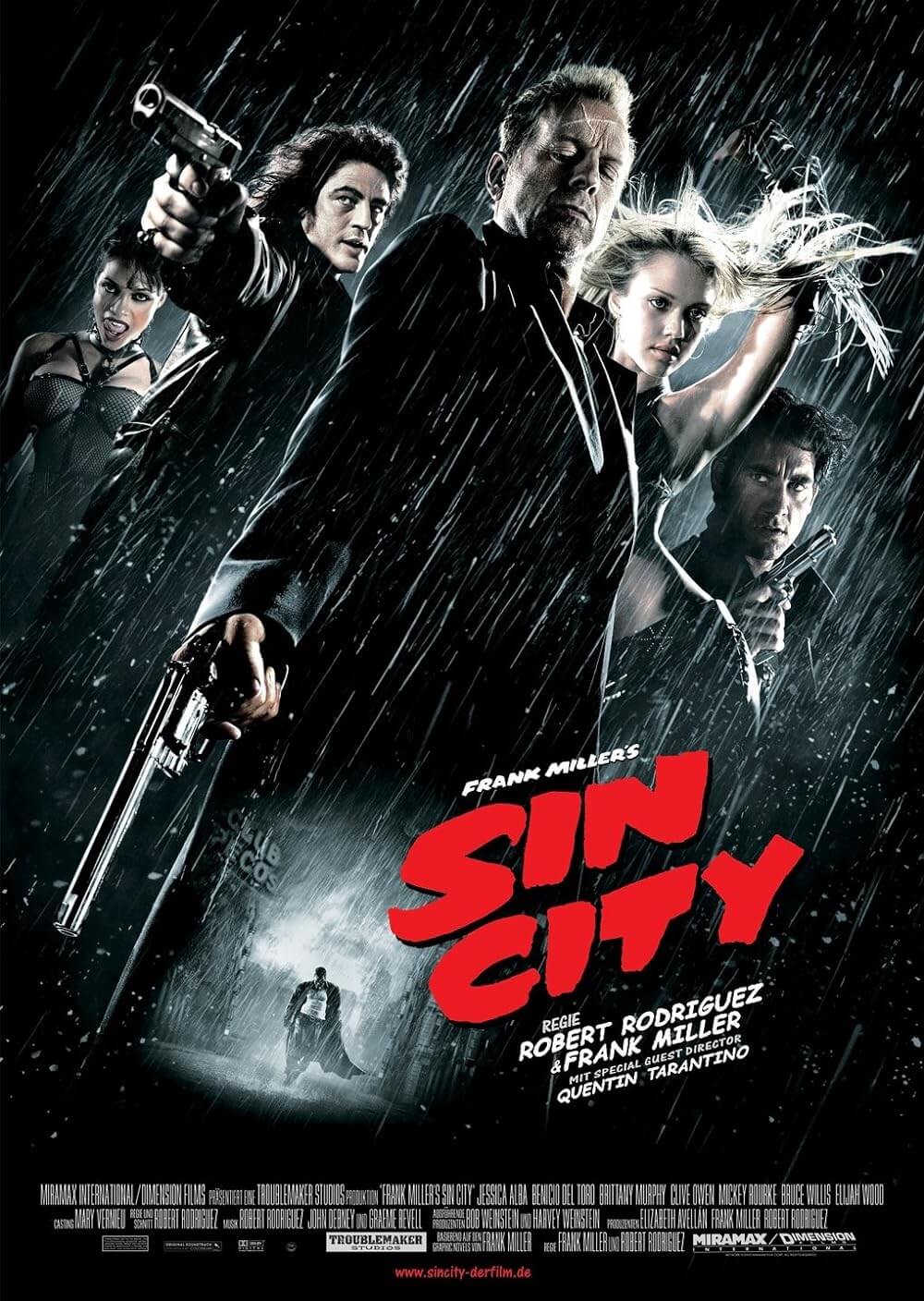

Arriving with an electricity that was at once shockingly violent, beautifully stylized, and questionable in its rather exploitative treatment of its female characters, Sin City was a freight train whose engine was an unstoppable force of energy that could have just kept going and going. The sequel to Frank Miller and Robert Rodriguez’s 2005 outing, Sin City: A Dame to Kill For, returns to that black-and-white world of film noir, which has been filtered through the expressive methods of comic book exaggeration and cinematic showmanship, nine years after the fact. Rodriquez’s original proved what others (like Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow) failed to—that a green-screen environment could be every bit as atmospheric as actual sets. And he used the tech to create backdrops that could only exist in a realm where pulp fiction and film noirs of the 1940s and 1950 were emphasized through comic book style. But whether it’s the long break between films or simply the tonal sameness of the stories themselves this time around, the sequel, while an entertaining return to this unique stylistic blend, lacks many of the qualities that made the original such a breakthrough.

After the original, Rodriguez developed the sequel in-between his other projects and tried to reorganize his original cast, as well as add some new players (among those mentioned and never signed were Angelina Jolie and Johnny Depp). In the meantime, some of the original cast passed away (Michael Clarke Duncan, Brittany Murphy), and others became too busy, and the years went by until production began in 2012. Credited with the screenplay, Miller’s masculine protagonists in Sin City: A Dame to Kill For still growl lines through coated throats of booze and cigarettes, narrating their ultra-violent tales about troubled women and murderous, corrupt villains. As before, Miller has been credited as co-director alongside Rodriguez (who also serves as editor and cinematographer), since Miller’s original graphic novels, which have been closely followed, inform the film’s visual structure. And save for a new story written especially for this film, the agreeable end result feels like we’re back in Basin City among those dark heroes, power-hungry officials, and desirable women.

Like the 2005 film, A Dame to Kill For is comprised of several overlapping stories, but these seem more related to the original’s tales than to each other. In fact, only about one-third of the film could qualify as a sequel; the other two-thirds occur before the events in Sin City. Most obvious is how the filmmakers have gone out of their way to inject the fan-favorite character Marv, that square-headed savage played by Mickey Rourke, into more than half of the film, whereas he appeared in only a third of the original. It all opens with a segment from Miller’s book Just Another Saturday Night, a trifle prologue about Marv giving some sadistic college brats what-for after they torture a few innocents. Next up is Miller’s written-for-the-screen original, The Long Bad Night, where a young hotshot gambler, Johnny (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), clears the table of the wrong backroom poker game, hosted by the dastardly Senator Rourke (Powers Boothe). Rourke teaches the kid a lesson, not that it stops Johnny from returning to do it again.

The film’s centerpiece is the titular A Dame to Kill For, featuring Josh Brolin as Dwight (originally played by Clive Owen). Reluctantly lured back to an old flame, the irresistibly sexy Ava (Eva Green), Dwight is manipulated by the calculating femme fatale into murdering her tycoon husband (Martin Costos). When he does, she double-crosses him, backed by her inhuman bodyguard Manute (Dennis Haysbert), her newfound cop-lover Mort (Christopher Meloni), and her mob ties. Meanwhile, Dwight teams with the savage whores of Old Town, their leader Gail (Rosario Dawson) and assassin Miho (Jamie Chung), to deliver Ava’s comeuppance. And the final story is Nancy’s Last Dance, which picks up years after That Yellow Bastard from the original film. The story finds stripper Nancy (Jessica Alba, generally terrible) heartbroken over the death of her savior, Det. Hartigan (Bruce Willis), who watches over her as a ghost. Vowing revenge on Senator Rourke for his effective cover-up of Nancy’s earlier kidnapping by his son, Nancy and Marv team up to dispose of Rourke once and for all.

Perhaps desensitization is to blame, or perhaps Rodriguez doesn’t approach this material with the same energy he once did, but the stories in this sequel proceed in a baseline fashion, without the euphoric heights found in the original. Rodriguez still manages some gorgeous black-and-white compositions, however—often inflected with primary reds, blues, and yellows, and often relying on silhouettes or painterly flourishes that border on pure art. Many of those compositions involve his adornment of Green (including a kaleidoscopic sequence in a pool), whose fascinating noir character belongs on a list with Barbara Stanwyck and Jane Greer as an archetypal femme fatale actress. Green’s sultry-eyed presence as a “goddess”, much as in the recent 300: Rise of an Empire, another Miller property, becomes the saving grace of the film. Also excellent are Gordon-Levitt’s cocky card-sharp and a campy appearance by Christopher Lloyd as a back-alley doctor. Elsewhere, the cameo-laden cast keeps us involved in a game of spot-the-celebrity (amid the names are Ray Liotta, Stacy Keach, Jeremy Piven, Juno Temple, and Lady Gaga).

Overall, the inventiveness of the filmmaking demonstrated in Sin City goes into auto-pilot here, resulting in more of the same. No new ground is broken, and the possibilities of a superior 3D presentation enhanced by the CG-assembled environments aren’t realized. The ever-forward narrative thrust of the stories in Sin City made that film an intense pleasure from which a person could not look away, whereas Sin City: A Dame to Kill For seems muted by comparison. These are similar types of yarns to be sure, and all the pulpy and comic elements are in place, but there’s an almost intangible, elusive emptiness to the production that lingers throughout. It’s not enough to sour the experience completely, but it’s a quality that cannot be ignored, and likely results from the lacking sense of discovery here that otherwise impelled the original film. Nevertheless, moments of greatness do occur, and the audience is rapt throughout, just with less unbridled enthusiasm than when we last visited Miller’s world nine years ago.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review