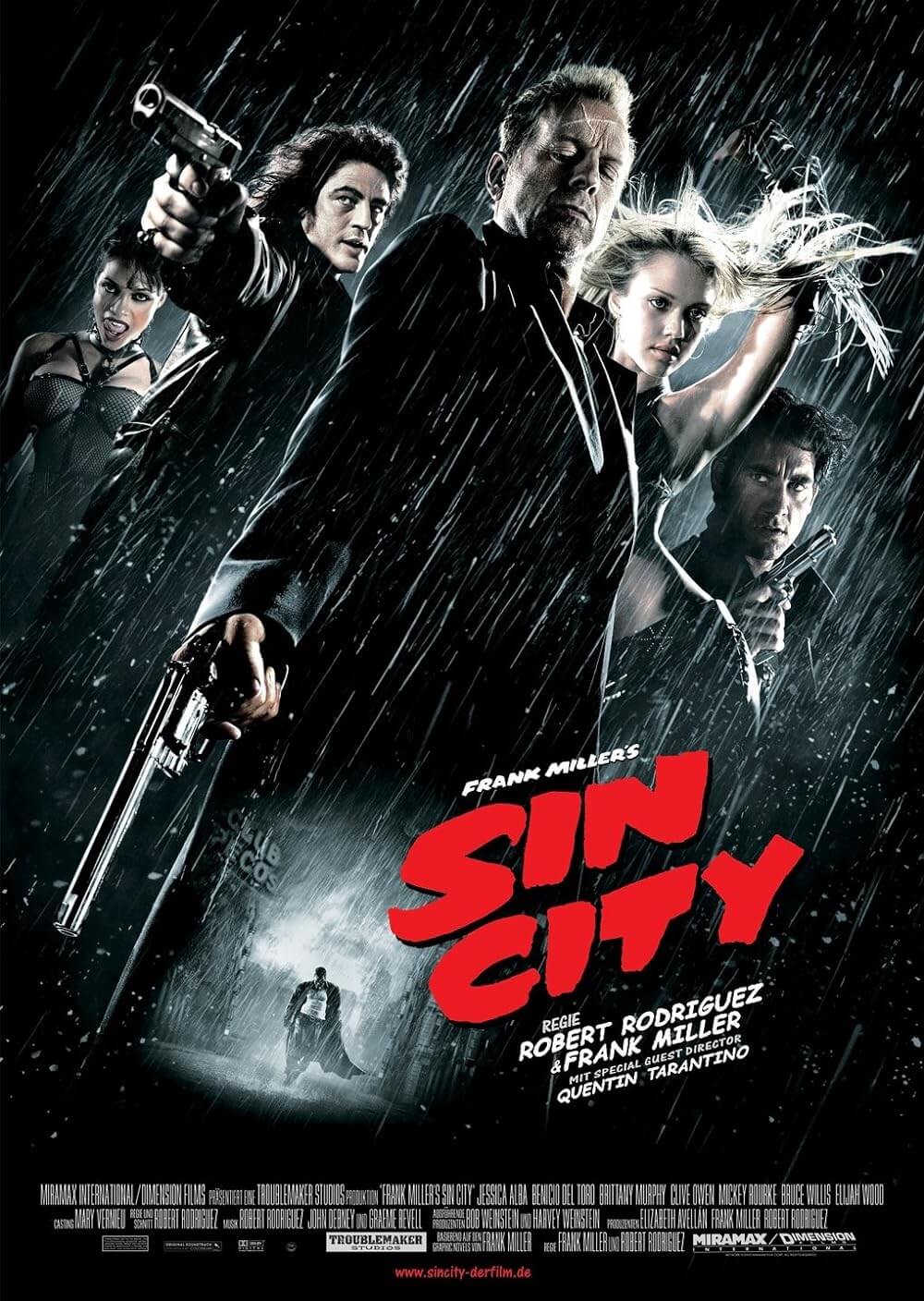

Sin City

By Brian Eggert |

A motion picture of smoky film noir aesthetics and comic book unrealities, Sin City proceeds with a boozy score, ultra-violence, and rampant sexuality. Such are elements that—when combined with black-and-white photography, splashes of vibrant color, men in long trenchcoats with guns, sleazy dames with attitude, and moody narration—emit a primal, visceral atmosphere saturated into every scene. At once seductive and abhorrent, it’s an experience that cannot be ignored, whether you’re offended or disgusted by it, or rapt by its unrelenting style. Robert Rodriguez’s 2005 hit adapts stories from Frank Miller’s Sin City graphic novels published throughout the 1990s, and in them, he finds a unique kind of cinema where style reigns supreme. And not just the obvious visual luster achieved in the film’s fantastically shadowy presentation, where hard-boiled tales of Mike Hammer and Phillip Marlowe from the 1940s and 1950s are influences. In a most Tarantino-esque flourish, Rodriguez takes inspiration from various genres in film and literature and exaggerates them, amplifying them to comic book extremes until he compiles them into something so innovative it can only be described as new.

Of course, the novelty of both the film and its presentation has tapered with an insurgence of post-Sin City rip-offs, send-ups, and stylistic copycats. The film has been taken for granted as a result. Shooting entirely in green screen environments, Rodriguez was free to create expressive black-and-white environments by way of computer technology, breaking the high-contrast monochrome palette for the occasional (often) flush of red, green, and a particularly nasty use of yellow. Rodriguez shot fast on digital and edited on a computer, as he had done before, but he finally put that technology to good use here. Rodriguez is an impatient filmmaker. He doesn’t want to take all day to set up the lights and erect a stage to capture a shot that might last a few seconds. He’s a pioneer of digital cinema. Take that how you will; the mixed artistic results with Once Upon a Time in Mexico and three Spy Kids features speak for themselves. But Rodriguez’s usually slapdash visual sense is enhanced by his devotion to Miller’s source material, which he used like storyboards and, because of it, he generously gave Miller co-director credit.

Sin City’s greatness resides in how well Rodriguez cuts into Miller’s books, severs a vein, and then plugs it into his own film, where its pulse is instrumental. Indeed, it’s a disservice to Miller’s books and the lurid nature of the storytelling to suggest Sin City is about visuals alone. With just visuals and not the forward-moving stories at its center, one gets something more akin to The Spirit, an abysmal project from 2009, directed by Miller on his own. The power of the simple, interconnected narratives on display here is undeniable. Each one hosts a similar trajectory and monolithic characters: Violent, gruff-voiced, scar-faced, masculine heroes launch a bloody, hell-bent mission to protect a younger, vulnerable woman who’s become the prey of an even more violent, sexually deviant male villain. The stories take place in an unknown era, where one character claims the latest vehicle is an old classic, which suggests the stories take place in the past, but a later scene shows a character on a cell phone. The effect recalls a pointedly comic style, perhaps best sampled from the small screen’s Batman: The Animated Series—a combination past-future world that doesn’t exist in any known place or time, and could only exist on the comic’s page or in film.

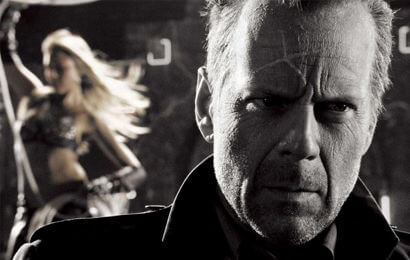

Rodriguez makes the best imaginable use of his impressive cast by typecasting them in a good way, especially the leads. Bruce Willis evokes a Robert Mitchum-in-Out of the Past-type as Hartigan, the last good cop in Basin City, a standard role for the actor. From Miller’s story That Yellow Bastard, Hartigan’s days are numbered with a nasty heart condition, and so he resolves to no longer ignore the city’s crooked senator (Powers Boothe) and his pedophile son (Nick Stahl). Hartigan winds up framed and in jail for all his heroism, but years later, after his release, he once again comes to the rescue of the now-grown victim, stripper Nancy (Jessica Alba). But after Hartigan’s last, castrationy encounter with the senator’s son, the creep has become a warped monstrosity known as Yellow Bastard. Another frame-job drives the second story, from Miller’s The Hard Goodbye, which follows Mickey Rourke’s Marv, a brutal thug with mental issues. Marv’s malformed, Frankenstein’s Monster-face reminds us that Rourke used to be a looker until he became a boxer, and then opted himself into lousy plastic surgery to fix his boxing scars. Marv goes on a kill-crazy rampage when, after a night of blissful sex with prostitute Goldie (Jamie King), he awakens to find her dead and himself framed for her murder. Pummeling his way through the underworld leads him straight to the top—to a farm where shrilly calm Kevin (Elijah Wood) cannibalizes women, among them his scantily clad parole officer (Carla Gugino).

Rodriguez makes the best imaginable use of his impressive cast by typecasting them in a good way, especially the leads. Bruce Willis evokes a Robert Mitchum-in-Out of the Past-type as Hartigan, the last good cop in Basin City, a standard role for the actor. From Miller’s story That Yellow Bastard, Hartigan’s days are numbered with a nasty heart condition, and so he resolves to no longer ignore the city’s crooked senator (Powers Boothe) and his pedophile son (Nick Stahl). Hartigan winds up framed and in jail for all his heroism, but years later, after his release, he once again comes to the rescue of the now-grown victim, stripper Nancy (Jessica Alba). But after Hartigan’s last, castrationy encounter with the senator’s son, the creep has become a warped monstrosity known as Yellow Bastard. Another frame-job drives the second story, from Miller’s The Hard Goodbye, which follows Mickey Rourke’s Marv, a brutal thug with mental issues. Marv’s malformed, Frankenstein’s Monster-face reminds us that Rourke used to be a looker until he became a boxer, and then opted himself into lousy plastic surgery to fix his boxing scars. Marv goes on a kill-crazy rampage when, after a night of blissful sex with prostitute Goldie (Jamie King), he awakens to find her dead and himself framed for her murder. Pummeling his way through the underworld leads him straight to the top—to a farm where shrilly calm Kevin (Elijah Wood) cannibalizes women, among them his scantily clad parole officer (Carla Gugino).

Already there are two stories with heroes and whores, and eyebrow-raising gender roles to be sure. The questionable content continues in Rodriguez’s take on Miller’s The Big Fat Kill, in which Clive Owen plays Dwight, an ultra-cool nice-guy-killer on the lam. He’s shacked up with dippy waitress Shellie (Brittany Murphy), whose cop boyfriend Jackie Boy (Benicio del Toro) soon disturbs the unwritten agreement between the powers of the mob and police, and Basin City’s red light district, known as Old Town, where prostitutes control their own. Dwight tries to cover up Jackie Boy’s inevitable death to save his dominatrix-lover Gail (Rosario Dawson), but soon pimps and cops led by gold-eyed enforcer Manute (Michael Clarke Duncan) come into Old Town looking to settle old scores. By now, the viewer inevitably questions why almost every female onscreen is either a prostitute, a stripper, none-too-bright, or half-naked. Any serious defense of Sin City‘s treatment of women is impossible, but it’s also missing the point. Feminism and equal rights gender politics have no place here. Look to film noir and crime fiction, where women were often represented as either sex objects or femme fatales; and now exaggerate those gender roles to comic book extremes, and remove any semblance of the censorship that hindered Miller’s inspirations. What you’re left with is Sin City.

Surely Miller’s male-exceptionalism, chauvinism, and pure sexism have saturated his printed works from Hard Boiled to 300, and elsewhere these qualities seem out of place or uncharacteristic for the material, but in Sin City, they seem suitable, if not appropriate. After all, this is a film noir comic book come-to-life, and Rodriguez reminds us of this when his heroes are shot several times and get up for more, or when villains are shot and they’re propelled twenty yards into the air. Because the backdrop of every scene has been animated with CGI and inserted in post-production, there’s a separation between the characters and their environment that suggests these brutal, larger-than-life figures have leaped from the page onto the screen. And while Rodriguez does much to underline the comic-embellished nature of Miller’s source through the cartoonish, sometimes humorously over-the-top violence, he channels Miller’s imagery through iconic compositions. Wet city streets, silhouettes of solid black or sometimes solid white profiles, figurative actors performing in singular roles, and enough atmosphere to lose yourself in—Rodriguez has doused his picture in visual and thematic styles, and it’s undeniably an achievement.

Surely Miller’s male-exceptionalism, chauvinism, and pure sexism have saturated his printed works from Hard Boiled to 300, and elsewhere these qualities seem out of place or uncharacteristic for the material, but in Sin City, they seem suitable, if not appropriate. After all, this is a film noir comic book come-to-life, and Rodriguez reminds us of this when his heroes are shot several times and get up for more, or when villains are shot and they’re propelled twenty yards into the air. Because the backdrop of every scene has been animated with CGI and inserted in post-production, there’s a separation between the characters and their environment that suggests these brutal, larger-than-life figures have leaped from the page onto the screen. And while Rodriguez does much to underline the comic-embellished nature of Miller’s source through the cartoonish, sometimes humorously over-the-top violence, he channels Miller’s imagery through iconic compositions. Wet city streets, silhouettes of solid black or sometimes solid white profiles, figurative actors performing in singular roles, and enough atmosphere to lose yourself in—Rodriguez has doused his picture in visual and thematic styles, and it’s undeniably an achievement.

Structurally, Sin City works best in its theatrical format; subsequent cuts on home video offer an extended version or the different “episodes” segmented for individual viewing. But the initial version’s momentum is unmatched in the way it transitions between stories and loops back around to finish them. Rodriguez, who “shot and cut” the film, seemed to get so much right the first time around in terms of pacing and structure. But given its content and the reactions to its style-over-substance approach, enjoying the film depends less on structure than the viewer’s ability to accept this is not a real world, but an orgy of styles wrapped in intentionally outlandish embraces and overstatements. Even after nearly a decade since its release, this is still bold filmmaking, risky and brave, uncompromising and superlative. The content begs you to be shocked, yet beckons you into this harsh, extreme world with every touch of imagination and sensory effect embedded into the production. Rodriguez was never so energetic or creative behind the camera, and he hasn’t come close to achieving something so inspired since.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review