Sicario: Day of the Soldado

By Brian Eggert |

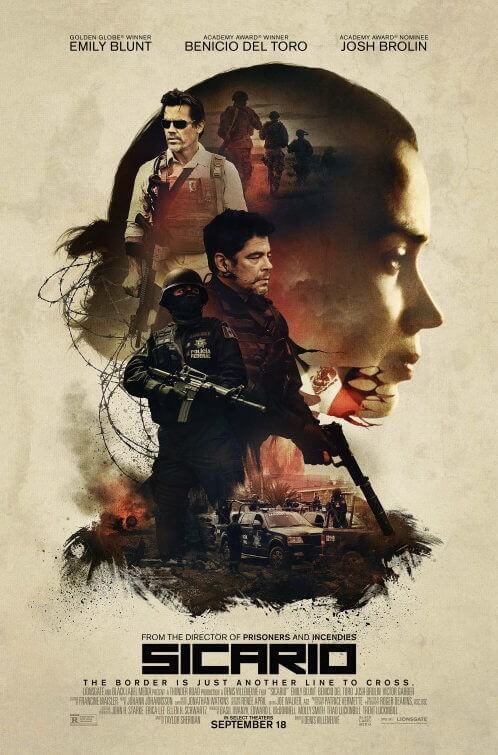

Director Denis Villeneuve’s thriller Sicario (2015), a film that requires additional viewings to grow, explored the ruthlessness of drug trafficking by exposing Emily Blunt’s green FBI agent to the blood-soaked reality of the Mexican cartels. Government spooks Matt Graver (Josh Brolin), complete with flip-flops and shorts, and the mysterious lawyer-turned-vengeful-assassin Alejandro (Benicio Del Toro), exposed Blunt’s character to an underworld that chews her up and spits her out. For the curious sequel, Sicario: Day of the Soldado, Blunt is nowhere to be found, as the protagonist took a cue from the title (which means “hitman”) and shifted to Alejandro by the end of the first film. But returning is screenwriter Taylor Sheridan, who, in addition to writing the original, also penned Hell and High Water (2016) and made his directorial debut on Wind River last year. Sheridan brings his same measured, cold-blooded quality, tapping into relevant themes of immigration on the border between the U.S. and Mexico with a thorny moral ambivalence.

Unfortunately, after Donald Trump enforced his “zero-tolerance” policy on anyone who enters the U.S. illegally, landing thousands in detention centers and “tender age” facilities for the young, Sicario: Day of the Soldado puts forth some distressing ideas. The opening titles suggest an alarmist fantasy world in which the Mexican cartels find it more profitable to smuggle people across the border than their annual $13 billion drug industry—an absurd notion, to be sure. Among the immigrants are Muslim terrorists who suicide bomb American stores, inciting the Secretary of Defense (Matthew Modine) to unleash Matt Graver on the Mexican cartels in a “no rules this time” CIA war. The very setup of Sheridan’s script at this point (perhaps unintentionally) fuels the hysteria of Trump supporters who fear that all immigrants are criminals, if not terrorists, as opposed to people just looking for a better life. And while the impetus for the entire film proves unfounded and xenophobic, as the inciting terrorists were American citizens, the border paranoia remains an ingrained part of the film.

After Washington, D.C. conveniently re-labels the drug cartels as terrorist organizations, Matt uses his unconventional black-ops methods to entice the cartels to destroy each other. With Alejandro serving as a precision scalpel, Matt’s task force carries out a false flag operation by kidnapping Isabela Reyes (Isabela Moner), the daughter of the most powerful cartel in Mexico, and makes a rival cartel look responsible. Then they stage a rescue, pretending to be the DEA, and plan to return Isabela to her family in a dangerous exchange. But during their transport of Isabela, Mexican police attack in a rousing mid-film shootout involving several military Humvees on a desert road, leading to some unwanted press. As it turns out, “POTUS doesn’t have the stomach for this,” and Matt’s icy superior (Catherine Keener) orders him to wipe out any trace of the operation—including Alejandro and Isabela. As one might expect, Alejandro is not pleased, and he takes a journey for which John Ford’s The Searchers (1956) was an apparent influence.

Sheridan’s story clips along at a steady pace, though he’s writing from a might-means-right ideology that lends the film a certain bland and familiar machismo. Marked by Brolin’s tough guy dialogue and Del Toro’s inscrutable expression, Sheridan ultimately has fewer dimensions to his characters. Whereas, say, Alejandro’s human motivations in Sicario came in surprising waves, there’s little growth or revelation in this sequel. And there’s no character, like Blunt’s, who stands outside it all, looking on with horror as the U.S. breaks countless laws to stop the lawless. Still, a shocking turn in the final third of the film has the possibility to go somewhere entirely unexpected, but instead, it turns into a conventional twist that feels beneath the material’s gravitas. In each of his screenplays, Sheridan’s writing has a way of using predictable genre tropes and disguising them with hardened dialogue and grave situations.

Italian director Stefano Sollima—whose experience in Mafioso dramas (the TV series Gomorrah) and gritty cop yarns (ACAB: All Cops Are Bastards, 2012) primed him to replace Villeneuve at the helm—makes his Hollywood debut here. Although, Sollima goes for a Villeneuve-lite style throughout, and he’s not supported by the beauty of Roger Deakins’ cinematography. Dariusz Wolski replaced Deakins, and though confidently shot, he hardly achieves the same stunningly empty vistas as the original. Meanwhile, the very concept of a sequel to Sicario seems strange, since the 2015 film made only a modest $50 million domestically and ended without the promise of more to come. Regardless, it’s refreshing to see something like Sicario: Day of the Soldado happen, as the sequel is neither part of an established intellectual property or particularly hot on viewers’ minds. Nevertheless, the Powers That Be believed in the material enough to take a chance on an unlikely follow-up, which could set a new precedent for Hollywood sequels—even a trilogy, which seems to be on the horizon.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review