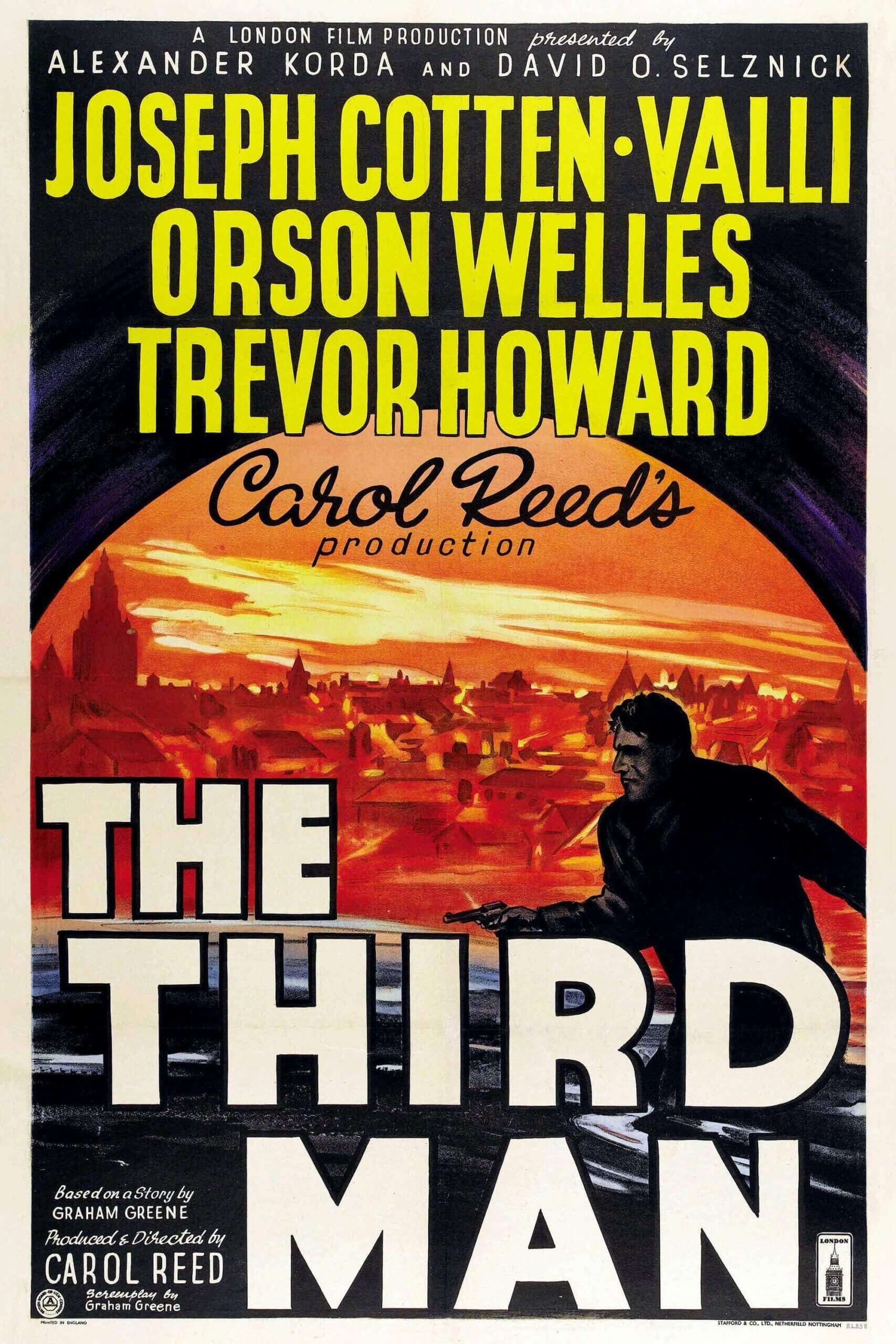

Shutter Island

By Brian Eggert |

From his earliest work onward, Martin Scorsese has always pondered the manner in which his characters contend with their guilt, personal tragedies, and sense of displacement. He’s shown us a hoodlum who holds his hand over a candle’s flame for a crude form of self-flagellation that soothes Christian guilt. He’s peered into the impenetrable psyche of a loner cabbie, finding desires to both become a hero and lash out through violence. His characters have banged their heads against the wall as they curse themselves; they’ve gone out wandering late at night only to find that the night bites back; they’ve seen the ghosts of patients they could not save; and they’ve been nailed to a cross.

From the pretext of a thrilling murder mystery, Shutter Island slowly develops into Scorsese’s first venture into the genre of psychological horror, as the film’s entire arrangement concerns the disturbing ways in which people manage their inner demons. Through maddened sociopaths and the scarred psyche of the story’s hero, Scorsese underscores his long-existing exploration of our external responses to inner stimuli. Based on the novel by author Dennis Lehane, the script by Laeta Kalogridis allows the director to delve into material that he has long contemplated; only here he’s using a more potent visual language. In doing so, Scorsese pays homage to filmmakers that he’s long admired by employing the gut-punch imagery of Samuel Fuller and the unrelenting suspense of Alfred Hitchcock.

Seemingly a police procedural set on the dynamic stage of an insane asylum, the story progresses into the director’s most virulent portrayal of a protagonist’s environment serving as a manifestation of inner conflict. Much in the way that Travis Bickle succumbed to New York City in Taxi Driver or Howard Hughes lost himself to his germaphobia in The Aviator, U.S. Marshall Tedd Daniels (Leonardo DiCaprio) becomes influenced by the atmosphere of his surroundings both in body and mind. The setting is Shutter Island, an isolated rock in Boston Harbor that houses Ashcliffe, an asylum for the criminally insane. Teddy and his new partner, Chuck Aule (Mark Ruffalo), are sent there to investigate a missing inmate, a mother (Emily Mortimer) who murdered her children. Upon their arrival, both men find the scenery menacing and the hospital’s staff peculiar. There’s a strange mannerism about everyone they speak to as if they’re all privy to the same frightful secret that no one will speak of. But just as the doctors seem to be harboring this mystery, so too are the prisoners.

Teddy and Chuck conduct interviews with doctors and patients and their sense that something is wrong within Ashcliffe grows with every encounter. Take the hospital’s creepy and elusive administrator, Dr. Cawley (Ben Kingsley), who always seems to circumvent Teddy’s probing. Another of the staff, Dr. Naehring (Max von Sydow), is more direct in his ability to outwit and therefore provoke Teddy. Outside the hospital’s walls, an immense storm builds and promises to trap the Marshalls there for some time. Meanwhile, the situation and conditions force Teddy to recall tragic events from his past, his time as a soldier at the liberation of Dachau, and the death of his wife (Michelle Williams) at the hands of an arsonist. Represented through surreal dream imagery, these flashbacks are gorgeous and haunting, more so even than the warped inmates on display in Ashcliffe.

How much we’re drawn in is contingent on DiCaprio’s astonishingly good performance. This is the fourth collaboration between him and Scorsese, and the director has done wonders to mature him into more than just a pretty face. With The Aviator and The Departed, DiCaprio has displayed incredible versatility. Here, the actor begins as a film noir cop, but as Ashcliffe works Teddy over it strips down layers of the character, thus adding layers to the performance. Also wonderful are Kingsley and Von Sydow as the sinister doctors, as well as Jackie Earl Haley and Mortimer who play disturbed patients. Scorsese has brought together an incredible cast, and watching this group of actors bring life to this scenery is surely something to behold.

Much will be made of the ending. Some will leave scratching their heads, questioning if it makes any sense. Some will understand that it doesn’t necessarily have to make sense. After seeing the film and soaking up the events in the story, Shutter Island will improve if watched again and absorbed as a whole, with the viewer aware of how it ends. There are details throughout that build to and hint at the big reveal coming in the end, and knowing what happens will help involve the viewer on another level. But the film isn’t about how the story leads to the twist, the moment that will inevitably lose some viewers incapable of suspending their disbelief. This work of genius is about Scorsese’s creation of mood, the incredible swell of suspense of which he’s only channeled before in his superb remake of Cape Fear.

Scorsese has remarked that with Shutter Island he wanted to make the kind of film that he likes to watch. With that, evident are influences ranging from film noir to Samuel Fuller. High contrast lighting and the 1950s production design capture the noirish tone of the feature, placing the film not in a realistic world, but a world that with its fedoras and stylish dialogue will feel familiar to those versed in the 1950s era of cinema. But Fuller’s influence is more specific. In terms of both narrative and setting, Scorsese’s film recalls Fuller’s Shock Corridor, a picture about a reporter who checks himself into an insane asylum to find a murderer but then goes mad himself. Moreover, Scorsese has taken a concept that would normally be reserved for Fuller’s brand of B-movie and elevated it to the level of art.

Every setpiece in the film is expertly used as a device through which Scorsese builds punishing suspense and furthers the psychological elements of his thriller. Ashcliffe mutates from a massive psych-ward into a living expression of the monsters scratching away inside Teddy’s post-traumatic stress-infused head. Suddenly the bars, inmates, doctor, and hurricane all have double meanings that apply to Teddy. Throughout, the director maintains an unbelievable tension, as if around every dark corner there’s something terrible waiting for Teddy. Sometimes the terrible things are the deranged inmates of Ashcliffe, but mostly they inhabit the horrible memories recalled in Teddy’s mind. And with that feeling of uncertainty both in the setting and the protagonist, Scorsese sends his audience reeling in discomfort, fear, and anxiety. It’s staggeringly effective.

The ending is something in the way of Hitchcock’s Psycho, in that what happened isn’t as important as the skill with which it’s presented. No one thinks of those Hitchcock thrillers and remembers only the ending. Rather, they remember bravado passages such as the shower scene, or the way Anthony Perkins strangely turns his neck when he leans over the counter to examine the registry. Shutter Island is all about those incredible “pure cinema” details. It’s about the setting, the ever-present sense that something is dreadfully off, the ghastly and intriguing dream imagery, and the madhouse presence of the asylum. It’s about a mise-en-scène driven by emotion and paranoia and the perpetuation of unknown horrors—the method more than the nature of the madness.

The film summons Hitchcock in another way, in that this is Scorsese’s Vertigo. Both films contain dream imagery, damaged protagonists plagued by their traumatic past, and propel uncertainty in the viewer about the events therein. In both, what we see doesn’t always make logical sense if talked out scene for scene. In a way, each sequence is its own whole. Hitchcock’s Vertigo was dismissed as nonsense upon its initial release, much like how the majority of critics are at present shrugging off Shutter Island as merely an ample thriller. But Hitchcock’s film is now considered one of the Master of Suspense’s very best. With time, perhaps Scorsese’s film will be revisited and appreciated for the atmospheric psychological mind-bender it is.

Shutter Island won’t be perfect on your first viewing. So see it twice, and the second time around watch it from a distance. Forget about the story and how it manipulates the audience throughout, imperfectly or not. Though the scenario dwells on that recurrent Scorsese theme of guilt management, aligning perfectly within the director’s body of work, themes aren’t really the purpose of a film like this. Instead, lose yourself in the details—the wicked splendor of the production, the stark power of the visuals, and cinematographer Robert Richardson’s shot compositions that are so beautiful they could be framed. Scorsese has conjured up a nightmarish cinematic display of his talents, quite unlike anything he’s shown us before. That he’s still surprising us with his mastery of the craft after so many years makes it easy to pronounce this film as some kind of masterpiece.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review