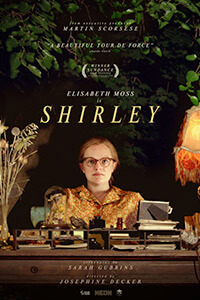

Shirley

By Brian Eggert |

Shirley was adapted from Susan Scarf Merrell’s 2014 novel of the same name, and screenwriter Sarah Gubbins employs a narrative structure that makes good use of director Josephine Decker’s style. The screen story might be viewed as somewhat conventional stuff, reminiscent of many other biopics about famous authors as seen through the eyes of a younger admirer. Its subject, beleaguered author Shirley Jackson, is played to incredible effect by Elisabeth Moss, in a performance that captures the troubled headspace of her character. Decker’s film takes place, most of the time anyway, from the perspective of the eponymous author whose delirium stems from bouts of severe depression, alcoholism, and pill-popping. Shirley doesn’t so much encapsulate Jackson’s life as give it definition through the process of writing Hangsaman, her second novel, published in 1951 and based on the real-life disappearance of a student named Paula Jean Welden, who never returned from a woodland walk. What follows is a blend of fact and fiction that allows the viewer to understand the author’s sometimes warped perspective; however, her behavior may be the only rational response given her surroundings.

The film takes place in a small Vermont town adjacent to Bennington College, where Shirley’s husband, professor Stanley Edgar Hyman (Michael Stuhlbarg), lectures about literary theory. With just one novel and several short stories to her name, most recently “The Lottery” in the pages of The New Yorker, Shirley has been relegated to the status of a so-called faculty wife. Stanley also oversees her work; he stewards her productivity and critiques her output, arguing about whether she has the energy to take on a new project when she can barely will herself out of bed. When we first meet them at a cocktail party at their home, both are properly soused and exchanging not-so-loving barbs before an audience of entertained colleagues. Our entry point into their world is Stanley’s newly arrived teaching assistant, Fred (Logan Lerman), and his wife, Rose (Odessa Young), who will stay with Stanley and Shirley until they find a place of their own. Fred spends his days trying to build a career in academia, while Stanley volunteers Rose to become their new housekeeper—a job that requires her to oversee Shirley, who doesn’t leave the house, and ensure that she doesn’t interfere with his ongoing affairs.

What begins with two couples writhing in each other’s company—the superior academics joke that their new “simpleton” guest will deliver nothing but dull conversation, while the younger couple finds the older two intolerably eccentric—shifts into a new dynamic. Fred settles into his role on campus as an instructor and budding lecturer, while Rose begins an uneasy friendship with Shirley. The author soon sees Rose as a stand-in for the subject of her new book, the missing Paula Jean Welde. The dutiful Rose comes to recognize that she has been sidelined and forgotten, while her husband’s behavior begins to mirror Stanley’s suspicious late-night faculty conferences and sexual disinterest. Shirley even suggests a vague romantic connection between the two women. Decker portrays their connection in a subtle materialization, even if their sameness is overstated in their final moment together. David Barker’s abrupt edits suggest their fragmentation, complete with extreme close-ups and unfocused shots. Several uses of mirrors also capture their fractured states as women in a male-dominated academic community, while Tamar-kali’s discordant piano and strings add to the effect.

Decker follows her meta-infused breakout Madeline’s Madeline (2018) with a film that, in terms of the story alone, is familiar. Formally, there’s a hodgepodge quality to the execution. Sturla Brandth Gróvlen’s off-kilter cinematography makes us feel as though we’re under Shirley’s spell, employing extreme close-ups and seasick camera movements from her perspective. Shirley speaks in intermittent voiceover from her text; she seems to view the world in shallow focus; and she visualizes her book in a series of recurring, fuzzy waking dreams. But Decker also places the viewer in Rose’s head with a couple of surreal dream sequences. It’s not always certain whose perspective Shirley hopes to identify with, and Decker alternates between Shirley and Rose freely, drawing connections between them that lead to a climactic moment where they seem to converge and finally understand one another. Through Rose’s arc, we come to realize what Shirley has been through, and thus what, perhaps, Paula Jean Welde avoided (“Maybe disappearing was the only way anyone would notice her,” Rose observes).

Decker follows her meta-infused breakout Madeline’s Madeline (2018) with a film that, in terms of the story alone, is familiar. Formally, there’s a hodgepodge quality to the execution. Sturla Brandth Gróvlen’s off-kilter cinematography makes us feel as though we’re under Shirley’s spell, employing extreme close-ups and seasick camera movements from her perspective. Shirley speaks in intermittent voiceover from her text; she seems to view the world in shallow focus; and she visualizes her book in a series of recurring, fuzzy waking dreams. But Decker also places the viewer in Rose’s head with a couple of surreal dream sequences. It’s not always certain whose perspective Shirley hopes to identify with, and Decker alternates between Shirley and Rose freely, drawing connections between them that lead to a climactic moment where they seem to converge and finally understand one another. Through Rose’s arc, we come to realize what Shirley has been through, and thus what, perhaps, Paula Jean Welde avoided (“Maybe disappearing was the only way anyone would notice her,” Rose observes).

Those familiar with Jackson’s writing will see the birthplace of her themes, ranging from madness to isolation to claustrophobia. Even the central location, a vine-covered bohemian house with musty air, feels like a textured and earth-toned place surrounded by the ever-present sound of birds chirping by day and frogs croaking by night. One suspects that, in different light, it could be the quintessential haunted house, complete with creaky wood staircases and a dinner table setting that breeds nasty confrontations. Jackson’s written work has received renewed interest in recent years thanks to Mike Flanagan’s superb Netflix limited series, The Haunting of Hill House, from 2018, based on the 1959 book that also inspired Robert Wise’s The Haunting (1963) and Jan de Bont’s abysmal 1999 version. To a lesser extent, the adaptation of Jackson’s 1962 novel We Have Always Lived in the Castle in 2018 also sparked some interest in the writer. And there always seems to be another version of her “thrillingly horrible” short story “The Lottery” coming to television. For most of us of a certain age, “The Lottery” was required reading in grammar school. For me, it was the start of a deep mistrust and cynicism toward humanity.

Shirley might be seen as a crystallization of Shirley Jackson’s worldview and writerly preoccupations. When being unseen and betrayed drives Rose to madness, she follows the trajectory of both the author and the author’s protagonist in Hangsaman, giving us some insight into the titular character. All at once, what seemed like a biopic from an outsider’s perspective becomes a sly deconstruction of Shirley’s psychology from the outside in. Even though some of the visual techniques seem obvious (there’s a distracting number of establishing shots of birds and Nature), the story structure is decidedly effective. And then there are the performances. Young and Lerman barely keep up with Moss and Stuhlbarg, who are terrific in each of their manic scenes together. Though it’s a tale of women empowering themselves, Shirley is messy and uneasy, as perhaps it should be. Both Shirley and Rose must be torn to shreds before they can piece themselves back together again, and even then, the result contains a tinge of madness. Then again, going a little crazy might be the sanest response of all.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review