Shaun of the Dead

By Brian Eggert |

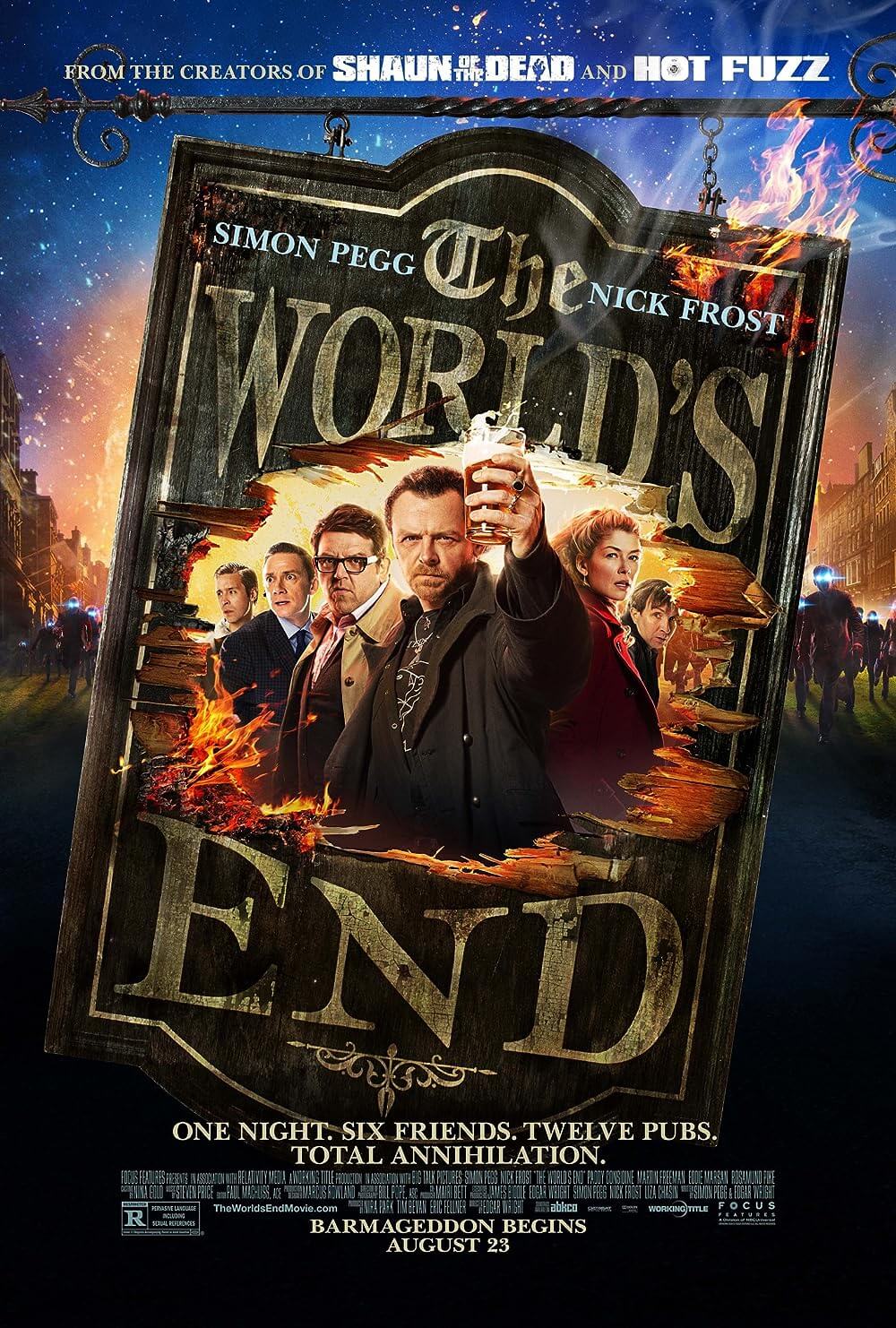

Call it the “Blood and Ice Cream trilogy” or the “Three Flavours Cornetto trilogy” or simply the “Cornetto trilogy.” Whatever name you assign, the three films by British director and co-writer Edgar Wright, co-writer and star Simon Pegg, and costar Nick Frost have developed a cult following, and for good reason. After collaborating on Britain’s Channel 4 television show Spaced (1999 to 2001), the trio of talents went on to make three features together: Shaun of the Dead (2004), Hot Fuzz (2007), and finally, The World’s End (2013). Each embraces a particular genre, and in each film, there appears a Cornetto brand frozen ice cream cone with a flavor correlating to the plot. A strawberry-flavored cone appears in the former’s bloody zombie survival story; the blue-label original flavor appears in the middle buddy-cop actioner; the latter features a mint-chocolate flavor to match the alien invasion paranoia scenario of their supposedly last film together in this style.

Shaun of the Dead launches the trilogy with a “zombie rom-com,” an ambitious label achieved by its prevailing hilarity, scares, romantic sentiments, and graphic doses of gore. Not since An American Werewolf in London (1981) has there been a film that so carefully balances its dark comedy, three-dimensional characters, and genuine chills. Although their American celebrity (followed by Paul, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, and the third and fourth Mission: Impossible entries) didn’t begin until Shaun of the Dead debuted in theaters, Wright, Pegg, and Frost laid the groundwork for their future efforts together on Spaced. And their first film closely relates to the structure of the show, which centers on a group of young underachievers who live together in a north London flat and seem ever unable to decide what to do with their lives. The show offered cultish movie, comic book, and television references ranging from Star Wars to Evil Dead II. And Wright, who directed every episode of the show’s two-season, fourteen-episode run, developed his distinctive visual style behind the camera. But since its release, Shaun of the Dead and the other Cornetto films have been inaccurately called “spoof” or “parody” titles, though they deserve to be considered far more in terms of their originality within the comedy genre.

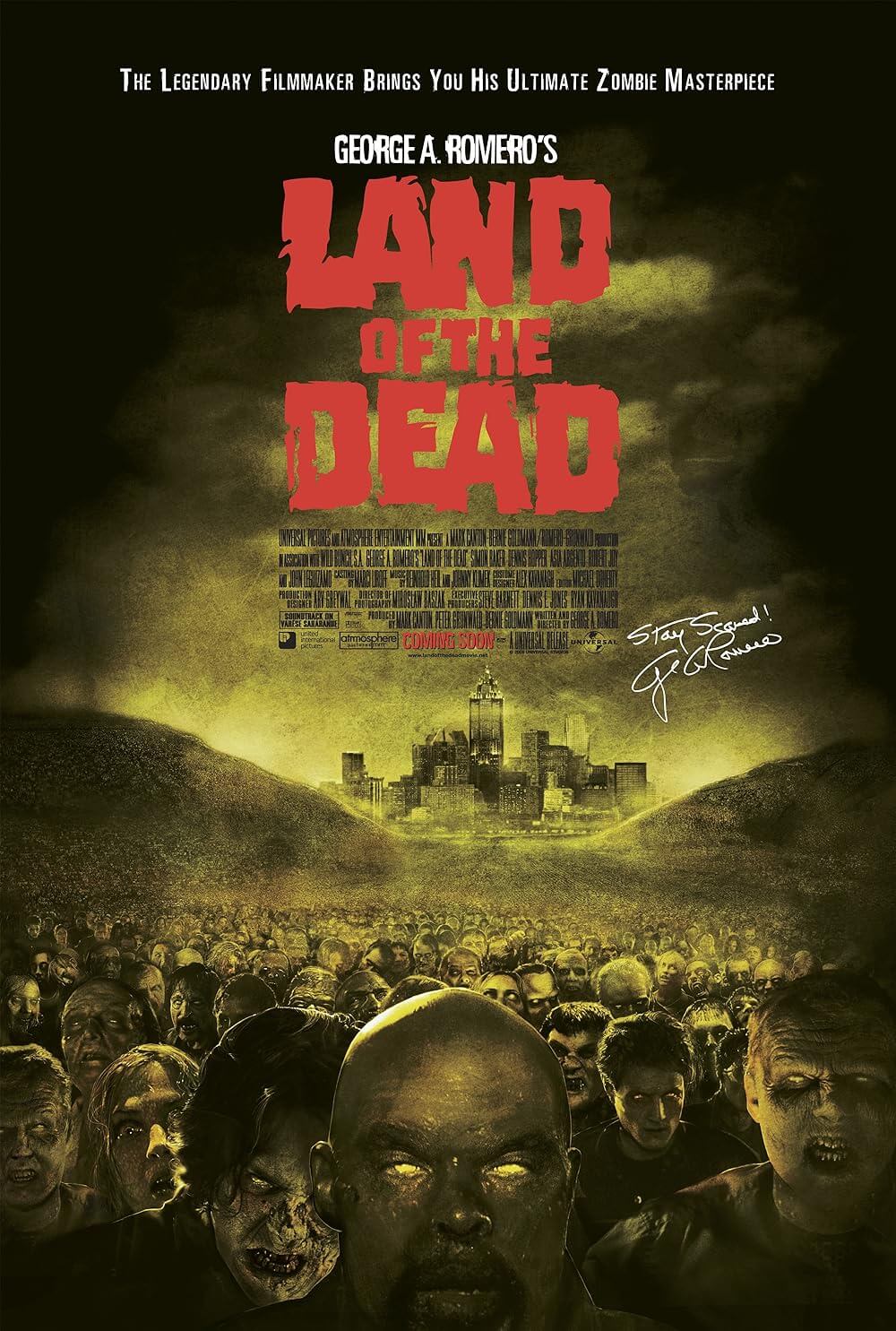

Upon its arrival in 2004, Shaun of the Dead would be a major component in the re-emergence of zombies in pop culture in the early 2000s, a movement that has continued over the last decade and developed (a word chosen with some hesitation) from a cult genre into widespread popularity (and perhaps oversaturation) with AMC’s hugely popular televisions series The Walking Dead. Although zombies have been around since the 1930s and standard zombie iconography began with George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968) and Dawn of the Dead (1978), the source of this reemergence began with another British film, Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later (2002), which reinvented the zombie structure. Boyle’s unexpected hit brought about Zack Snyder’s remake of Dawn of the Dead (2004) and Romero’s own continuation with Land of the Dead (2005). Once a midnight movie staple, zombies are everywhere today —in video games, books, and even blockbusters such as World War Z. In America, gun ranges offer zombie targets, and most cities feature their own version of a “zombie pub crawl” around Halloween. When it was released, Shaun of the Dead was greeted as an original kind of parody of cult zombie favorites by Romero, Sam Raimi (The Evil Dead trilogy), and Peter Jackson (Dead Alive). Although generally well-reviewed, few critics saw Shaun of the Dead as more a parody than the post-modern masterwork it happens to be.

Just as Romero has used zombies as an allegory for racism, consumerism, and sociopolitical apathy, Wright uses zombies as a metaphor. Stuck in arrested development, Shaun (Pegg) spends every night at his local watering hole, the Winchester Pub, with his best friend and flat-mate Ed (Frost). His girlfriend Liz (Kate Ashfield) almost seems like a third wheel, and she tries to reach Shaun by explaining that their present, routine-based situation isn’t how she wants to spend her life. Rutted and unable to break his dull routine, Shaun is a social zombie. In an early sequence after a night of drinking, he slogs along on his normal routine down to the local convenient store, passes stagnant traffic and the usual smattering of blank-faced pedestrians caught in their own routines; he buys a soda and Cornetto for Ed and returns to play Xbox with his friend before work. The next day, after another night of heavy drinking when Liz breaks up with him, Shaun goes through the same routine, not noticing how this time, everyone outside has been zombified. The downbeat daily grind of the dreary living and the lifeless creep of the undead are virtually identical. Progressing through the film to this point, an astonishing thirty minutes in, were half-noticed signs of the looming zombie apocalypse, which has now arrived in full force, but Shaun is still trapped in his routine and fails to notice.

Despite the blend of genres, the film reaches for emotional and situational realism and therein resists some of the characteristic horror traits of a zombie yarn. In place of a shadow-strewn horror world, much of Shaun of the Dead’s action takes place on a bright day in a London suburb. When they become aware of the zombie threat, the film’s characters react by calling for emergency services; and when that’s busy, Shaun and Ed plop onto the couch and watch the news for answers. Even after they dispose of two zombies in their backyard, Shaun and Ed return to the news to assess the situation, as we all might do. These characters are relatable and behave in ways that make sense emotionally, as opposed to the dramatic, survival-minded decision-makers of most zombie movies. After arming himself with a cricket bat, Shaun’s first instinct is to rescue his now ex-girlfriend Liz and his mother Barbara (Penelope Wilton). In a hilarious sequence, he and Ed mull over the best attempt at rescue, and then set out to gather Shaun’s loved ones and hole up at the Winchester.

In a standard three-act structure, Shaun of the Dead follows a setup, journey, and resolution, the journey segment involving Shaun and Ed making their way to Barbara and Shaun’s stepdad, the zombie-bitten Philip (Bill Nighy), and then to Liz’s where they also gather her mates David (Dylan Moran) and Dianne (Lucy Davis). None of these characters feel anonymous to the story, and each has a significant emotional connection to either Shaun or one of the others. Consider how the first to die, Philip, finally arrives at a teary understanding with his estranged stepson before turning. Or how David’s unrequited love for Liz becomes a source of embarrassment so extreme he turns a gun on Shaun. Of course, the most heightened relationships exist between Shaun, Ed, and Liz. By the end, Ed has been bitten, and in turn, Shaun is forced to accept that his life must move onward by setting aside his “boy time” with Ed in place of a mature relationship with Liz. In essence, Shaun is de-zombified through the course of the film. And so, these are not inconsequential “body count” characters designed to perpetuate onscreen death, but rather characters in a tightly structured plot wherein almost nothing feels unnecessary to its larger meaning.

Likewise, the humor in Shaun of the Dead is multi-layered—base, endearing, and pointedly referential without sacrificing the integrity of the characters or dramatic tension. One of the film’s most touching, ironic moments comes near the end when Ed, rekindling an earlier gag about flatulence, apologizes to Shaun in a teary moment marked by laughter and the line, “I’ll stop doing it when you stop laughing.” Any comedy that somehow makes a fart joke heartfelt is operating on a higher level than most. Wright and Pegg have also incorporated countless nods to their favorite zombie movies, each reference and homage disguised by the strength of their own story. Shaun works as a “sales adviser” at Foree Electronics (named after Ken Foree, star of Romero’s Dawn of the Dead) and attempts to make a dinner reservation at Fulci’s (tipping the hat to Italian horror maestro Lucio Fulci). Lines of dialogue such as “Join us” and “We’re coming to get you Barbara” are derived from Raimi and Romero films, but they’re delivered in such a way that the reference doesn’t feel out of place or forced within Shaun of the Dead’s context.

Likewise, the humor in Shaun of the Dead is multi-layered—base, endearing, and pointedly referential without sacrificing the integrity of the characters or dramatic tension. One of the film’s most touching, ironic moments comes near the end when Ed, rekindling an earlier gag about flatulence, apologizes to Shaun in a teary moment marked by laughter and the line, “I’ll stop doing it when you stop laughing.” Any comedy that somehow makes a fart joke heartfelt is operating on a higher level than most. Wright and Pegg have also incorporated countless nods to their favorite zombie movies, each reference and homage disguised by the strength of their own story. Shaun works as a “sales adviser” at Foree Electronics (named after Ken Foree, star of Romero’s Dawn of the Dead) and attempts to make a dinner reservation at Fulci’s (tipping the hat to Italian horror maestro Lucio Fulci). Lines of dialogue such as “Join us” and “We’re coming to get you Barbara” are derived from Raimi and Romero films, but they’re delivered in such a way that the reference doesn’t feel out of place or forced within Shaun of the Dead’s context.

Just as the referential humor fuses with the strength of the story, Wright and Pegg’s screenplay focuses on the same types of characters they explored together in Spaced. But the director also demonstrates his ability to incorporate genuinely scary horror elements into his already versed slacker comedy. The threat of death is very real in Shaun of the Dead, and when these characters die, they die grimly. In particular, David is torn apart by a frenzied horde that pulls out his insides even as he’s still screaming. Zombie bites are rendered with stringy, fleshy gobs and chunks, and there’s no short supply of fake blood onscreen. Such graphic moments are counter-acted by slapstick, like the synchronized pool cue beating to Queen’s “Don’t Stop Me Now.” More than just pure horror, however, Wright balances each frightening moment with a laugh or emotional turn to diffuse the situation. There’s a scene of extraordinary suspense and humor when the survivors make their way through a crowd of the undead by acting like zombies in half-hearted imitations. Or, when everyone has piled into Philip’s cramped car after Shaun has rescued Liz and her friends, Wright puts us through the wringer as, a moment after Shaun and Philip’s emotional breakthrough, Philip turns into a pale-eyed flesh-eater.

The balancing act in Shaun of the Dead is transcendent, ever playing with its genre, sense of humor, and style throughout. Somehow, Wright and his cast have the audience laughing and gasping and recognizing some obscure reference from start to finish. Our reactions are always multifaceted, shared equally in laughter, terror, and fond affection for lovable characters. Those who might describe the picture as a spoof—thus condemning it to the same category as parodic nonsense such as Airplane!, The Naked Gun, or Scary Movie —fail to see the postmodern originality of what’s before us. Shaun of the Dead, Hot Fuzz, and The World’s End: each film exists both inside and separate from their chosen genre, aware of and yet entirely independent from its sources. The titles in Wright’s “Cornetto Trilogy” rise above their genres into a unique plane inhabited by the likes of cineaste-savvy filmmakers such as Quentin Tarantino and Paul Thomas Anderson, a status where the words “spoof” and “parody” have no place.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review