Shame

By Brian Eggert |

Steve McQueen’s Shame takes a nonjudgmental and uncompromising view on sex addiction, a disease just as incapacitating as dependencies on alcohol, gambling, or narcotics. Sufferers pursue an all-consuming need for an orgasm, but the release brings no pleasure; after reaching a climax, they seek out another, and another, following a compulsive drive that can never be satisfied. The act itself no longer has meaning. A British visual artist and now two-time filmmaker, McQueen approaches his subject unflinchingly. Sexual acts are shown as emotionless experiences, merely another in a long series of fixes, and nudity comes into view without stimulation. The topic itself may cause viewers to shut out their potential empathy, but McQueen’s film challenges an audience to find his subject’s soul. As a result of the film’s challenging nature, this review will discuss the film in full detail and hopefully provide a few answers. Those seeking a spoiler-free review should look elsewhere. Then again, Shame is not a plot-driven film, and seeing the film unspoiled will hardly impact its effect.

Immersed in his character’s perspective, McQueen’s study follows Brandon, played by Michael Fassbender, an attractive thirtysomething office worker who lives in a sterile apartment in New York City. The city itself reflects the character; it’s a grim view of the metropolis, filthy and littered with graffiti, and refreshingly realistic. Brandon is successful in his unspecified job and has a seemingly exciting nightlife, but he secretly guards his affliction of satyriasis. When he ventures to singles bars with his talky boss David (James Badge Dale), his boss strikes out with corny pick-up lines, whereas Brandon’s long, penetrative glances at beautiful women lead to casual encounters. He’s responsive and attentive to women; therefore, they’re drawn to him. But Brandon’s entire day follows a routine of stimulation: he masturbates in the morning in the shower; again in the men’s room at his office; pornography fills his computer at home and at the office; he elicits the service of call girls; he’s never had a relationship last for more than a few months.

Though, Brandon isn’t looking to make a love connection; he has no more devotion to his conquests than a smoker has to a single cigarette. The sex itself proceeds mechanically. He may appear charismatic and passionate at first, but as the act carries on, Brandon’s face bares all. With his nameless partner reeling in ecstasy, Brandon displays desperation and pain. He no longer enjoys the experience; he needs it, and he hates himself for that. An early scene shows Brandon on a subway, where he spies an attractive woman (Lucy Walters) sitting across from him. The two exchange smiles, and as her stop approaches, she rises and takes hold of the pole near him, displaying her wedding ring. Brandon stands and takes hold of the pole as well, placing his hand just under hers, touching it, unconcerned about her commitments when a potential fix is in the making. As the subway comes to a stop, Brandon loses the woman in the crowd. In Brandon’s frantic searches like this one, composer Harry Escott’s solemn score crescendos until the peak moment or until disappointment, allowing us to sense the slow-brooding anguish tearing away at the character. He’s reminded of his guilt when his work suddenly takes his computer to clean a virus from the hard drive. When they find an excess of pornography, even David doesn’t believe it could be Brandon’s—whoever looked at that stuff must be a real sicko, David remarks.

Brandon’s lifestyle comes into question with the sudden arrival of his younger sister. A lounge singer with a damaged history, Sissy (Carey Mulligan) crashes on his couch and is determined to cling to her brother. Her presence disrupts Brandon’s routine, particularly when she beds David one night. Suddenly his sister becomes one of those anonymous encounters he and David search for, putting a face on the prey of Brandon’s predatory disease. Mulligan’s performance, in addition to realizing a tender rendition of “New York, New York,” is unlike anything we’ve seen from the usually innocent, charming actress from An Education and Drive. She’s secondary to Fassbender, as Sissy’s presence prompts a devastating degree of self-reflection for Brandon. As a result, he attempts to change by engaging in a “normal” date with a coworker, Marianne (Nicole Beharie), yet finds that when he actually feels something toward a sexual partner, he’s unable to perform. Sex has become something that requires emotional distance to fulfill, and his realization of this is devastating.

Brandon’s lifestyle comes into question with the sudden arrival of his younger sister. A lounge singer with a damaged history, Sissy (Carey Mulligan) crashes on his couch and is determined to cling to her brother. Her presence disrupts Brandon’s routine, particularly when she beds David one night. Suddenly his sister becomes one of those anonymous encounters he and David search for, putting a face on the prey of Brandon’s predatory disease. Mulligan’s performance, in addition to realizing a tender rendition of “New York, New York,” is unlike anything we’ve seen from the usually innocent, charming actress from An Education and Drive. She’s secondary to Fassbender, as Sissy’s presence prompts a devastating degree of self-reflection for Brandon. As a result, he attempts to change by engaging in a “normal” date with a coworker, Marianne (Nicole Beharie), yet finds that when he actually feels something toward a sexual partner, he’s unable to perform. Sex has become something that requires emotional distance to fulfill, and his realization of this is devastating.

Shame is not a sexy film, but the MPAA has stricken it with an NC-17 rating due to a preponderance of nakedness and sexual acts onscreen. When Brandon walks about his apartment exposed in the morning, Fassbender is on full-frontal display, and then he makes his way to the toilet to urinate. During scenes of intercourse, McQueen doesn’t supply a voyeuristic thrill; rather, the camera retains a view of Brandon’s tormented expression, all but unconcerned about what his lower half is up to. It’s difficult to imagine anyone describing Shame as erotic or enticing, as the emotions associated with the film’s sexuality are almost never enjoyable on any level other than artistic appreciation for what McQueen and Fassbender have accomplished. McQueen’s frankness allows us into the character’s head without reservation, and Fassbender’s portrayal gives it incredible dimension. His Brandon is not a self-satisfied addict blissfully content in his behavior, such as the characters in Downloading Nancy, for example. He is suffering, and for that, his story becomes a compelling one; his character is someone we want to see overcome his disease.

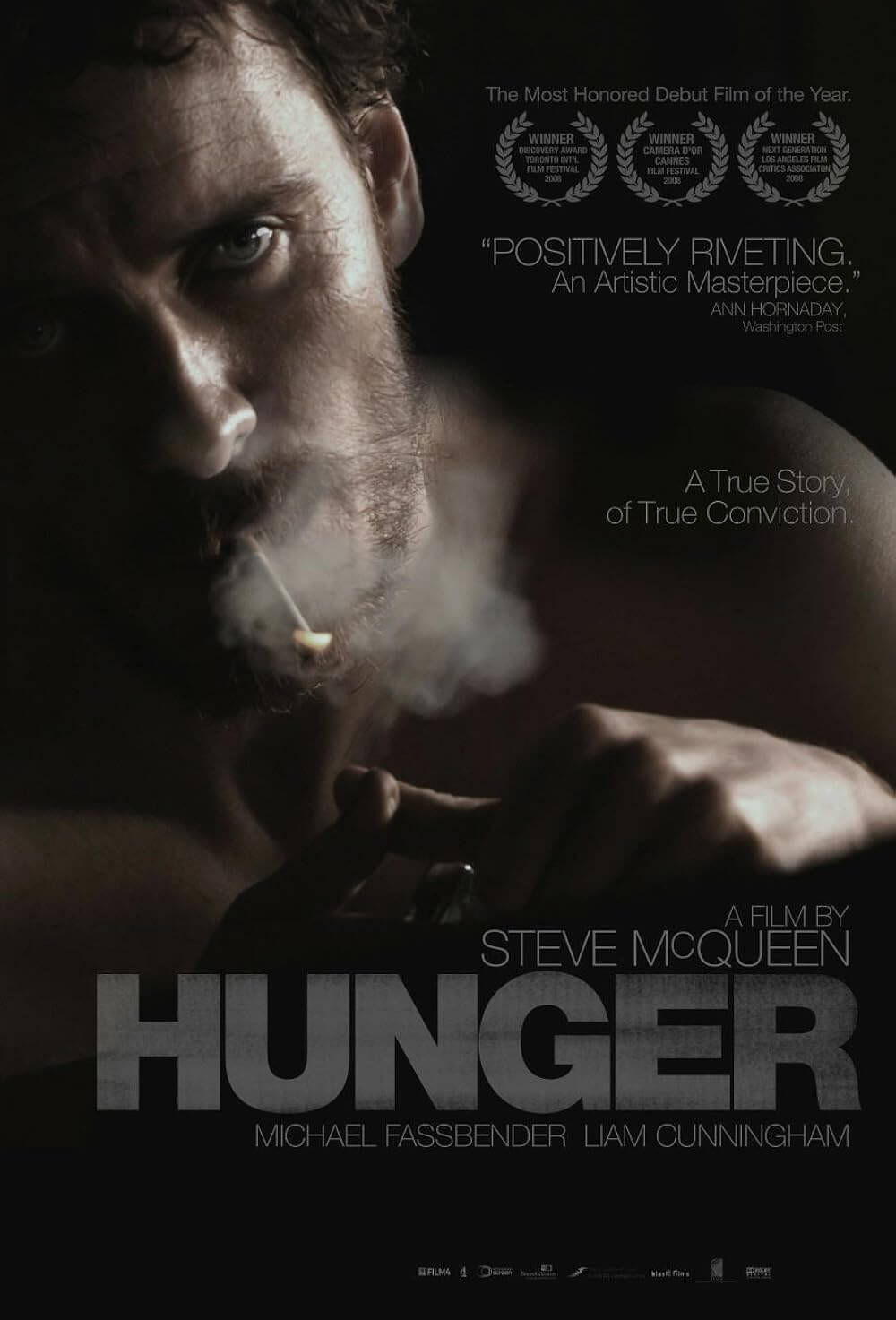

Given the film’s rating and subject matter, Fassbender’s Brandon will undoubtedly be another in the actor’s long line of underseen performances, but it’s also one of his very best. The actor reteams with McQueen, who directed him in Hunger, which starred Fassbender as IRA hunger striker Bobby Sands in an all-committing, staggeringly good performance. After that film, Quentin Tarantino cast him as a rigidly British film buff that goes undercover behind enemy lines in Inglorious Basterds. Fassbender remained largely on the indie film circuit, appearing in gems like Andrea Arnold’s Fish Tank. But 2011 has been his breakout year. This year he gave shattering intensity to Mr. Rochester in Cary Joji Fukunaga’s version of Jane Eyre. He followed that commanding performance with another in a box-office hit, playing an intense Magneto in X-Men: First Class, a role that, incredibly, surpassed Ian McKellen’s take. For another film in limited distribution, A Dangerous Method, David Cronenberg’s period piece about psychoanalysis, Fassbender portrays Carl Jung alongside Viggo Mortensen’s Sigmund Freud. But the actor shows little signs of slowing in both the number and quality of projects he’s attached himself to. Next year, he’s appearing in Steven Soderbergh’s spy actioner Haywire and Ridley Scott’s pseudo-Alien-prequel called Prometheus.

A few detracting critics have noted that McQueen’s film doesn’t say anything about sex addiction and that Fassbender’s character doesn’t grow within the story. Did they see a different film? This critic saw a character plagued not just by sexual addiction, but by a larger disease: solitude. Brandon is a singular beast, alone in the world, until his sister forces him to reflect on his behavior. After Sissy catches him masturbating and then shortly after sees pornography on his laptop, she pokes fun at him and calls him a weirdo. She doesn’t know the extent of it, of course, but Brandon does. Being exposed sends him on an outburst fuelled by humiliation and anger; first, he attacks Sissy, but later he empties his apartment of pornography and tosses it on the street. The larger problem is Brandon’s aloneness in life that allows his addiction to persist. With emotional connections like family or relationships, his addiction could not maintain in privacy, and so he avoids them, not because he wants to but because he must. Yet, his undeniable love for his sibling leaves him shaken by his indignity; he goes on a self-destructive path until, in the end, Sissy shakes him out of it.

A few detracting critics have noted that McQueen’s film doesn’t say anything about sex addiction and that Fassbender’s character doesn’t grow within the story. Did they see a different film? This critic saw a character plagued not just by sexual addiction, but by a larger disease: solitude. Brandon is a singular beast, alone in the world, until his sister forces him to reflect on his behavior. After Sissy catches him masturbating and then shortly after sees pornography on his laptop, she pokes fun at him and calls him a weirdo. She doesn’t know the extent of it, of course, but Brandon does. Being exposed sends him on an outburst fuelled by humiliation and anger; first, he attacks Sissy, but later he empties his apartment of pornography and tosses it on the street. The larger problem is Brandon’s aloneness in life that allows his addiction to persist. With emotional connections like family or relationships, his addiction could not maintain in privacy, and so he avoids them, not because he wants to but because he must. Yet, his undeniable love for his sibling leaves him shaken by his indignity; he goes on a self-destructive path until, in the end, Sissy shakes him out of it.

In a way, Shame becomes a film not only about sex addiction but about a culture of self-containment and a distancing between people. As technology and such “advances” like social networking prevail, human contact becomes unnecessary and perhaps Brandon is the result. There are others in the film enduring the same disease, although Brandon is an extreme case, imprisoned by his impulses. And no matter how troubled Sissy may be, she represents his freedom. Still, the film does not present a happy ending with Brandon altogether healed of his disease; the last scene suggests he no longer objectifies his conquests—a first step—but refuses to elaborate, and offers an open-ended conclusion, demanding an audience make their own conclusions. Beautifully shot in clean, long takes that immerse the viewer into Brandon’s world, the film doesn’t soon let us escape that world. Following Hunger, McQueen and Fassbender have accomplished another difficult film whose rewards are contained in its implacable truth.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review