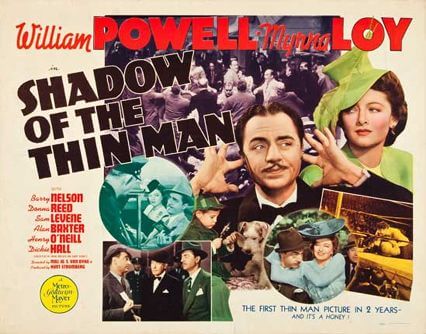

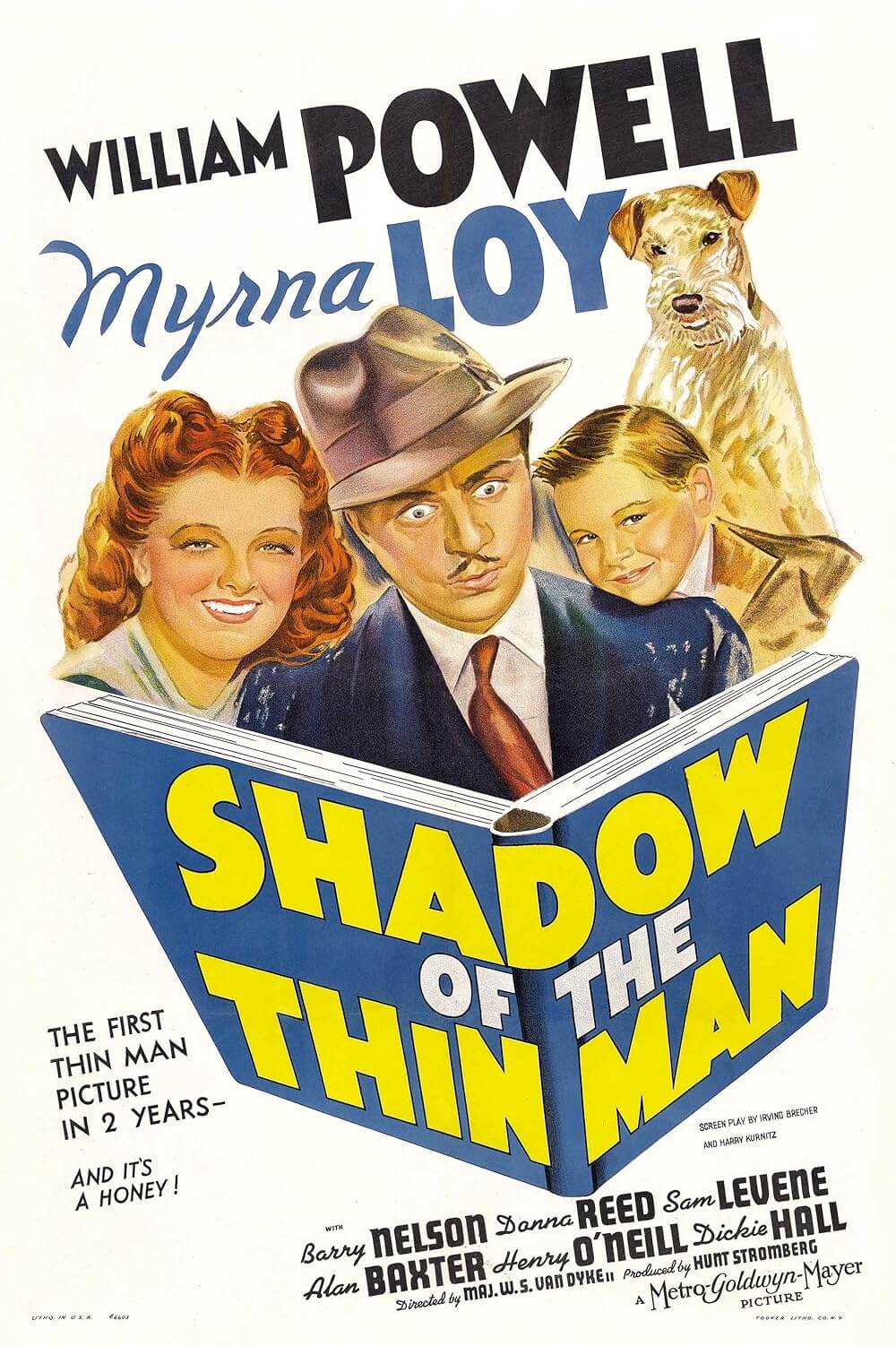

Shadow of the Thin Man

By Brian Eggert |

Trying to pinpoint the precise film on which the Thin Man series went on autopilot and became simply more of the same opens up a debate. Certainly, you could argue that the series had been on autopilot since its inception—that the same formula exists in each film, beginning with the original and continuing through both its first sequel, After the Thin Man, and second, Another Thin Man, and so on, until the last entry in 1947. After all, each of the six pictures in the franchise features the same components: witty verbal sparring between “retired” detective Nick Charles and his wife Nora, comic asides with their dog Asta or child Nicky, a labyrinthine murder mystery, and a grandstanding resolution wherein all suspects are gathered for the Big Reveal. The only difference in each is the specifics of the case at hand, whereas Nick and Nora remain their ever-charming selves, a reliable constant. Many might accuse the third sequel Shadow of the Thin Man of feeling like an obligatory continuation, but the proceedings are no less delightful, funny, or suspenseful than the sequels before it.

Author Dashiell Hammett had sold his Thin Man rights to MGM by 1937, which meant the studio could hire a writer less jealously devoted to his characters (and also less drunk) than Hammett, who provided the stories for the first three entries. Also departing from the franchise were the Hacketts, the husband-and-wife writing team responsible for the first three screenplays. In their place were Harry Kurnitz and Irving Brecher. Kurnitz, like Hammett, wrote pulp-fiction mysteries, but wasn’t nearly as successful; after arriving in Hollywood in 1938, he adapted his own stories into screenplays and also wrote I Love You, Again (1940) for a Powell and Loy programmer. In the decades to come, Kurnitz would adapt A Shot in the Dark (1964) and penned How to Steal a Million (1966), and he earned a reputation as a “court jester” among directors such as Billy Wilder and John Huston. Brecher was most famous for writing gags for big-name talent like Milton Berle, Mervyn LeRoy, the Marx Brothers, and for some comic contributions to The Wizard of Oz (1939). Working from a loose storyline by Elliot Paul, Kurnitz and Brecher were guided by producer Hunt Stromberg, and they embedded hilarious gags throughout. But not everyone was laughing.

Shadow of the Thin Man was released in late November 1941, just two weeks before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Although the film would still earn a profit, its box-office numbers were no doubt impacted by Americans’ call to action. Critics argued the series was beginning to slow and saw evidence that the Charleses, too, were “settling down”. The reviewer for the San Francisco Chronicle wrote that the Charleses “are beginning to rely a bit too emphatically on their rare delightful charm.” Moreover, Loy and Powell each had their share of hardships off-screen between the release of Another Thin Man and after Shadow of the Thin Man’s debut. Loy, ever the humanitarian, gave up her Hollywood persona for the next three years to volunteer with the Red Cross and raise money for the war effort, earning a spot for herself on Adolf Hitler’s “hate list”. She also divorced her first of four ex-husbands, risking her image as the “perfect wife”—established by the Thin Man series—in the process. Meanwhile, Powell’s life was beset by tragedy when his two ex-wives, Carol Lombard and Eileen Wilson (mother of his only child), both died unexpectedly. His previous fiancé, Jean Harlow, had also died in 1937. Fortunately, the actor married his third wife Diana Lewis in 1940, and the two would stay together for Powell’s remaining years.

Shadow of the Thin Man was released in late November 1941, just two weeks before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Although the film would still earn a profit, its box-office numbers were no doubt impacted by Americans’ call to action. Critics argued the series was beginning to slow and saw evidence that the Charleses, too, were “settling down”. The reviewer for the San Francisco Chronicle wrote that the Charleses “are beginning to rely a bit too emphatically on their rare delightful charm.” Moreover, Loy and Powell each had their share of hardships off-screen between the release of Another Thin Man and after Shadow of the Thin Man’s debut. Loy, ever the humanitarian, gave up her Hollywood persona for the next three years to volunteer with the Red Cross and raise money for the war effort, earning a spot for herself on Adolf Hitler’s “hate list”. She also divorced her first of four ex-husbands, risking her image as the “perfect wife”—established by the Thin Man series—in the process. Meanwhile, Powell’s life was beset by tragedy when his two ex-wives, Carol Lombard and Eileen Wilson (mother of his only child), both died unexpectedly. His previous fiancé, Jean Harlow, had also died in 1937. Fortunately, the actor married his third wife Diana Lewis in 1940, and the two would stay together for Powell’s remaining years.

Shadow of the Thin Man begins with the murder of a jockey at the racetrack, his death revealing an organized crime racket to rig the races. Nick finds himself thrust into the investigation by starstruck cops and journalists, specifically investigative reporter Paul Clark (Barry Nelson) and Lt. Abrams (Sam Levine, returning from After the Thin Man). This time, Nick doesn’t put up too much protest before conceding to the investigation, which involves a racketeer (Loring Smith), his innocent secretary (Donna Reed, before her big break on It’s a Wonderful Life in 1946), and a duplicitous dame (Stella Adler). Adler has some juicy scenes, the short-lived actress having adopted the method style in just three film roles before she retired and went on to become an acting coach and teacher for other method performers such as Marlon Brando and Robert De Niro. Adler smolders in her role, containing all the mystery and danger of a film noir femme fatale; and though her part is resigned to a few good scenes, it remains Adler’s most significant screen role—shocking, considering her input to the craft.

Much of the film humor occurs early in the picture and involves Nick struggling to acclimate to his seemingly still-new position as a father. Now about 4 years old, Nick Jr. (Dickie Hall) sports a military school uniform and he’s just as bright as his parents. In the opening scene, Nick takes his boy and Asta for a walk in the park (both of them on a leash). They sit on a bench so Nick can read Nicky a story, but our hero proceeds to read the racing form in a storybook format, “Once upon a time” and all. Without warning, Nick stands up and announces, “Something tells me that something important is happening somewhere, and I think we should be there.” Cut to Nora shaking Nick a martini. Parenthood hasn’t dried up Nick’s appreciation for the drink, as we see later during dinner when Nicky insists his father drink milk instead of a cocktail, and Nick begrudgingly agrees as if swallowing strychnine. Nick also grumbles about getting on a carousel with his son, but to save Nicky face in front of the other boys, he does it, with kaleidoscopic results. Elsewhere, Loy has one of her funniest moments in the series, at a wrestling match of all places. Nick learns that his wife has an affinity for the sport when she’s climbing all over him during the match, her face and body contorting as she watches the wrestlers—or performers, as Nora learns on the way out when she remarks to one of the wrestlers “I hope it comes out okay for you.” The wrestler, struggling in pain under his larger opponent, looks up, breaks character, and says with a smile, “Thanks lady!”

Much of the film humor occurs early in the picture and involves Nick struggling to acclimate to his seemingly still-new position as a father. Now about 4 years old, Nick Jr. (Dickie Hall) sports a military school uniform and he’s just as bright as his parents. In the opening scene, Nick takes his boy and Asta for a walk in the park (both of them on a leash). They sit on a bench so Nick can read Nicky a story, but our hero proceeds to read the racing form in a storybook format, “Once upon a time” and all. Without warning, Nick stands up and announces, “Something tells me that something important is happening somewhere, and I think we should be there.” Cut to Nora shaking Nick a martini. Parenthood hasn’t dried up Nick’s appreciation for the drink, as we see later during dinner when Nicky insists his father drink milk instead of a cocktail, and Nick begrudgingly agrees as if swallowing strychnine. Nick also grumbles about getting on a carousel with his son, but to save Nicky face in front of the other boys, he does it, with kaleidoscopic results. Elsewhere, Loy has one of her funniest moments in the series, at a wrestling match of all places. Nick learns that his wife has an affinity for the sport when she’s climbing all over him during the match, her face and body contorting as she watches the wrestlers—or performers, as Nora learns on the way out when she remarks to one of the wrestlers “I hope it comes out okay for you.” The wrestler, struggling in pain under his larger opponent, looks up, breaks character, and says with a smile, “Thanks lady!”

After three entries, each following the same basic formula as the fourth, with just a change of venue and shuffling of character, surely Shadow of the Thin Man doesn’t feel like the freshest of sequels. Contemporary critics noticed that the film relied heavily on Nick and Nora’s signature dash of cute—but how cute it is. Here, director W.S. Van Dyke (whose name is credited as “Major W. S. Van Dyke II” with increasing absurdity) capably delivers the Thin Man formula with every flourish of sophistication, liquor-frenzied antics, surprising mystery, and romantic delight that audiences expected from the series. It would be Van Dyke’s last entry in the franchise, having died in 1943. Loy later called him “one of Hollywood’s best, most versatile directors.” With Van Dyke’s sense of spontaneity intact, plenty of comic gags, and the inimitable screen presences of stars William Powell and Myrna Loy, Shadow of the Thin Man reminds us that, despite six films in the Thin Man series, it’s the consistency and enduring quality of these elements that kept contemporary audiences coming back for more, and retains the franchise’s place in film history.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review