Reader's Choice

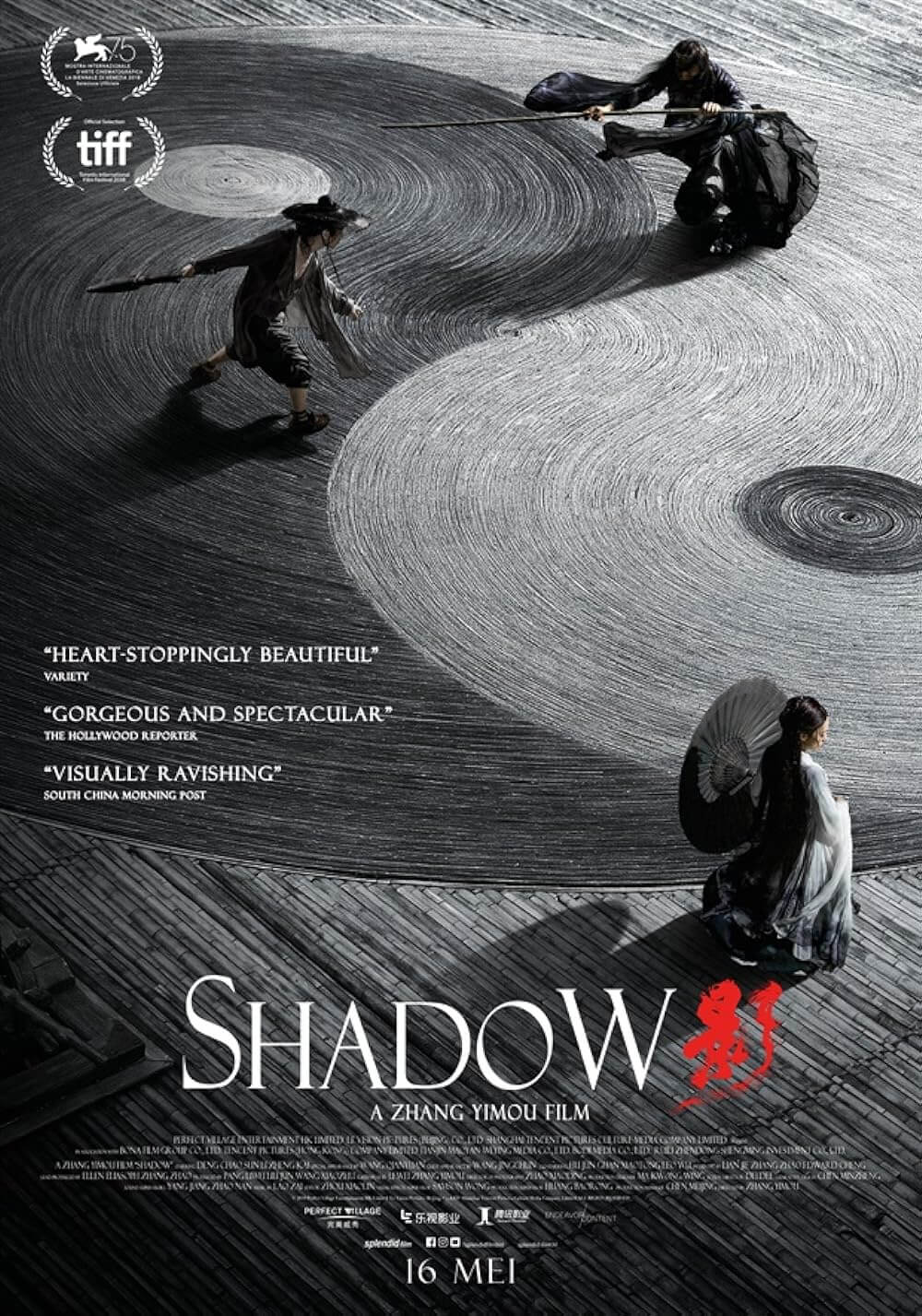

Shadow

By Brian Eggert |

Palace intrigue and ornate martial arts duels are just the surface of Shadow, Zhang Yimou’s stunning 2018 period epic of doppelgängers, zither duets, double-crosses, and monochrome colors splattered with blood. Nearly forty years have passed since China’s Fifth Generation filmmakers such as Zhang and Chen Kaige, graduates of the Beijing Film Academy, first started a modernization movement through experimental techniques and personal expression. But in all that time, there’s never been anything quite like this, a variation on wuxia stylization with an entrenched Yin-Yang symbolism that works its way into the film’s characters, themes, settings, and aesthetic. Although it follows Zhang’s disappointing would-be crossover adventure The Great Wall (2016), which awkwardly placed Hollywood talent like Matt Damon and Willem Dafoe into a Chinese blockbuster, Shadow recaptures the visual spectacle and historical source material of the director’s earlier wuxia trilogy—Hero (2002), House of Flying Daggers (2004), and Curse of the Golden Flower (2006)—and even surpasses them.

Based on an earlier screenplay by Zhu Sujin but rewritten by Li Wei and Zhang, the story draws from the legend of ancient China’s Three Kingdoms. In a repeated visual motif, the opening titles and set decorations in Shadow employ the image of black ink calligraphy, as though the whole film was sourced from the pages of the 14th century novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms by Luo Guanzhong, a veritable ur-text for many Chinese stories in literature and film. China’s rich and storied history has supplied no end of period pieces over the years, and Zhang’s treatment of this era has often been accompanied by fantasies that blend history and imagination with eye-popping colors—from the fallen leaves duel in Hero to the pastel gowns in House of Flying Daggers. By contrast, Shadow feels like a stagebound political drama penned by the Bard and drained of its color to render every character emblematic of their part in the prevailing Yin-Yang theme. It’s at times small scale and limited to the royal court, but it’s also not devoid of spectacle (a massive city invasion sequence late in the film is a stunner).

The story opens in the court of the Pei Kingdom, home to a young and arrogant King (Zheng Kai) whose city of Jingzhou is occupied by the Yang kingdom, headed by the fearsome General Yang Cang (Hu Jun) and his son Yang Ping (Leo Wu). The Pei Kingdom wants to regain control of Jingzhou, but they cannot afford war—the King has even written an “Ode to Peace” on dozens of semi-transparent panels that fill his court. In the opening scenes, Pei Kingdom’s brave Commander Yu (Deng Chao) returns from Jingzhou, having negotiated a one-on-one duel between himself and General Yang to determine the city’s fate. The King worries that Yu’s actions may lead to war, and to make things right, he offers his sister, Princess Qingping (Guan Xiaotong), to Yang Ping as a wife. But then Yang Ping offends the Pei Kingdom with a counteroffer: the Princess can be his concubine. It’s an offer that insults everyone involved, yet the King accepts it to maintain peace. The King also demotes Yu to a citizen class as punishment for causing this fissure between the Pei and Yang kingdoms.

The story opens in the court of the Pei Kingdom, home to a young and arrogant King (Zheng Kai) whose city of Jingzhou is occupied by the Yang kingdom, headed by the fearsome General Yang Cang (Hu Jun) and his son Yang Ping (Leo Wu). The Pei Kingdom wants to regain control of Jingzhou, but they cannot afford war—the King has even written an “Ode to Peace” on dozens of semi-transparent panels that fill his court. In the opening scenes, Pei Kingdom’s brave Commander Yu (Deng Chao) returns from Jingzhou, having negotiated a one-on-one duel between himself and General Yang to determine the city’s fate. The King worries that Yu’s actions may lead to war, and to make things right, he offers his sister, Princess Qingping (Guan Xiaotong), to Yang Ping as a wife. But then Yang Ping offends the Pei Kingdom with a counteroffer: the Princess can be his concubine. It’s an offer that insults everyone involved, yet the King accepts it to maintain peace. The King also demotes Yu to a citizen class as punishment for causing this fissure between the Pei and Yang kingdoms.

Yu’s motivations don’t immediately reveal themselves, requiring more than a half-hour to pass before the plot mechanics become clear. Yu isn’t the noble warrior he appears to be; rather, he is Jing, a peasant taken from the streets of Jingzhou long ago because he resembles the real Yu (also played by Deng Chao). Trained to be Yu’s “shadow,” Jing served as a decoy until Yu suffered a crippling wound from Yang Cang. Now, Jing, who trains under Yu and his clever wife Madam (Sun Li), has completely replaced Yu at court, fooling everyone in a scheme reminiscent of Akira Kurosawa’s Kagemusha (1980). These details are not revealed until after the King has demanded that Yu and the Madam play one of their famous zither duets, but the shadow awkwardly refuses the King, claiming he’s “not in the mood.” Only upon a second viewing of Shadow does the full weight and tension of these early scenes come into focus. Similarly, Yu’s bloodthirsty ambition is not apparent from the start. He seems bent on retaking Jingzhou and defeating Yang Cang at first; however, his master plan also involves a coup d’état.

The action plays out in two modes: The first involves duel sequences filmed in Shadow’s ever-present rainfall. Jing endures a punishing regiment under Yu and the Madam’s tutelage, preparing him for the upcoming duel with Yang Cang with “feminine” moves to counteract the fiercely masculine fighting style of the General. The duel sequences often appear in slow-motion, with raindrops and sprays of water moving along with the elegant, dancelike action. The second mode comes when Yu’s contingent of soldiers, led by Captain Tian (Wang Qianyuan), secretly invades Jingzhou as Jung and Yang Cang duel. These larger battle scenes feature dazzling imagery of soldiers donning makeshift scuba gear to breach the city’s borders and then sliding down the city’s streets on weaponized umbrellas, flinging daggers and arrows along the way.

But Shadow isn’t all about stylized martial arts and never-seen-anything-like-it-before battles. The drama resonates in a forbidden romance between Jing and the Madam, who might prefer the shadow to the real thing. Yu watches from a peephole as his wife and double make love, containing his mad jealousy and scheming his revenge. A subplot about Jing’s mother, too, not only resonates but leads to the film’s bloodiest display of violence when assassins corner Jing, impaling him with swords. Jing slices their throats and takes them down, and the audible spraying of blood from their jugulars recalls the sound from the final duel in Kurosawa’s Sanjuro (1963). Although somewhat neglected by the screenplay, Princess Qingping’s arc leads to a fateful confrontation with Yang Ping, the man who insulted her honor. However, Guan Xiaotong crafts a memorable character as the Princess, and her final smirk feels like a cheer-worthy victory.

But Shadow isn’t all about stylized martial arts and never-seen-anything-like-it-before battles. The drama resonates in a forbidden romance between Jing and the Madam, who might prefer the shadow to the real thing. Yu watches from a peephole as his wife and double make love, containing his mad jealousy and scheming his revenge. A subplot about Jing’s mother, too, not only resonates but leads to the film’s bloodiest display of violence when assassins corner Jing, impaling him with swords. Jing slices their throats and takes them down, and the audible spraying of blood from their jugulars recalls the sound from the final duel in Kurosawa’s Sanjuro (1963). Although somewhat neglected by the screenplay, Princess Qingping’s arc leads to a fateful confrontation with Yang Ping, the man who insulted her honor. However, Guan Xiaotong crafts a memorable character as the Princess, and her final smirk feels like a cheer-worthy victory.

Every moment in Shadow has added meaning, given how Zhang and production designer Ma Kwong Wing have turned the film into a black-and-white reflection of Yin-Yang philosophy. This dynamic of dark and light, feminine and masculine, passive and active, nobility and peasantry—and in this case, the real and shadow—works its way into the film’s design and story. Note how costumer Chen Minzheng creates stark black armor for Yang Cang and white robes for Jing, while Yu’s robes appear tattered and gray. Each character is marked by a predominant color that shares visual similarities with their opposite, acknowledging the dual relationship of Yin-Yang. As the title suggests, Shadow is an entire film in grayscale. With Zhao Xiaoding’s gorgeous cinematography accompanied by Samson Wong’s visual effects that render the backdrops with an artificial note, it’s as though the viewer was watching a modern play performed on a CGI stage. At court, the scenery looks more grounded; the court interiors have a diverse array of decorative panels, painted in an inkbrush style, that give modest scenes an intricate visual dimension and texture. The most stunning set must be Yu’s rain-slicked cave dwelling, complete with a Yin-Yang fighting area, which sets the stage for the film’s duels and romantic conflict.

Indeed, Shadow’s elaborate interplay of complementary forces in the film’s color scheme, martial arts duels, relationships between men and women, opposing kingdoms, and fighting styles has been beautifully rendered. Fans of purely actionized wuxia may feel underserviced by the political gamesmanship at the film’s center, but Zhang’s overall treatment from the mise-en-scène to the narrative meditates on the reciprocal nature of the universe, making every scene inseparable from its greater meaning. There are other pleasures, such as the intense zither performances and flute music, composed by Lao Zai (aka Loudboy). Or the dual performances by Deng Chao, who inhabits Yu and Jing so fully that you might second-guess your eyes. Shadow’s blend of theatricality and wuxia-inspired violence remains unique in Zhang’s career, delivering a film that feels bound by characteristics of the Chinese stage and cinema. For a filmmaker who constantly reinvents himself and tests the boundaries of his output, here’s a film that belongs on a list of his greatest achievements.

(Note: This essay was originally suggested and posted on Patreon.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review