Seberg

By Brian Eggert |

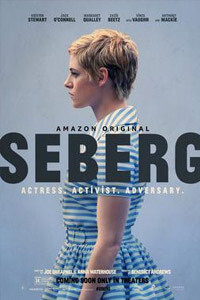

Seberg opens with a stagelike image of Kirsten Stewart tied to a wooden stake. Fire burns all around the performer, who appears in rags and with short-clipped hair. It’s a shot that may baffle the average viewer unfamiliar with the film’s subject, actress Jean Seberg. When she was discovered in late 1950s by despotic filmmaker Otto Preminger, her first role as Joan of Arc in 1957’s Saint Joan left Seberg scarred by Hollywood both physically and psychologically. She was literally burned when Preminger’s crew failed to contain the fire in Joan’s death scene, and she never recovered from the mental trauma of the director’s harsh manipulation. Even so, Seberg went on to a promising career, bouncing between the French film industry and Hollywood throughout the 1960s and 1970s. She was rendered iconic by Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless (1960), but she also appeared in Paint Your Wagon (1969) and Airport (1970). The events of Seberg, however, focus on the FBI’s counterintelligence program, called COINTELPRO, that under the direction of J. Edgar Hoover targeted progressive political activists and civil rights figureheads—everyone from Malcolm X to Muhammad Ali, and of course Jean Seberg.

The screenplay by Joe Shrapnel and Anna Waterhouse renders both Seberg’s life and the political issues in a shorthand that leaves them airless. Similar to last year’s Judy, the film takes a late segment from its subject’s life and uses that period as a method to understand the whole. But the ineffectual script hardly gets inside of Seberg’s head, and the film relies instead on the larger-than-life central performance to drive the picture. Fortunately, Stewart’s turn is more impressive than Renée Zellweger’s overwrought performance, and the actor has not poised herself for Oscar consideration in a vanity project. Stewart seems genuinely invested in Seberg’s story as a socially minded star whose image supported political causes. However, as signaled by the opening shot of Seberg as Joan of Arc, the film has reduced its titular character to a martyr whose life was torn apart by an unruly FBI investigation.

Seberg opens during the May 1968 riots in Paris, where the performer lives with her French husband, Romain Gary (Yvan Attal), whom she leaves behind for an audition in Hollywood. On the plane to America, she meets Hakim Jamal (Anthony Mackie), a leader in the Black Power movement. She genuinely wants to help, and she’s willing to use her celebrity to bring attention to the cause. She has also written sizable checks to various civil rights organizations in the past, including the Black Panthers and NAACP, but it’s her affair with Jamal that makes her a target of the FBI. Orders from Hoover demand that a “fuckwire” be planted in her bedroom to capture all the salacious details, which the agency then uses to ruin her life in the public eye. The FBI damages both marriages when they play the carnal audio for Jamal’s wife (Zazie Beetz), contextualizing the governments “war against black people in America” not so long ago. All these shady tactics lead to Seberg’s descent into alcohol and pills, but the outcomes prove even more tragic as the film proceeds.

Apart from the opening shot, director Benedict Andrews isn’t subtle in his use of symbolism that presents Seberg as a tragic figure. During a party scene at Seberg’s house, there’s a shot that lingers on sock and buskin masks, and the camera slowly zooms on the tragedy mask, behind which FBI agent Jack Solomon (Jack O’Connell) has hidden a wire. In a curious secondary storyline, Seberg follows Jack’s homelife with his spouse Linette (Margaret Qualley). He’s an idealistic sort, evidenced by his affinity for Captain America comic books, and so he finds himself at moral odds when his partner (Vince Vaughn) and boss (Colm Meany), both Hoover flunkies, delight in tormenting Seberg with a smear campaign that resorts to grotesque cartoons and media slander. The time spent on the one-note Jack only distracts from Seberg, leaving both characters to feel underrepresented.

Andrews, whose background in opera and stage productions is evident throughout Seberg, delivers a film whose symbolism and high dramatics seem ill-suited for such a simple-minded script. The film consists of provocative sex scenes, heated arguments, and dialogue that unsubtly telegraphs every interior emotion or political situation. Formally, the director doesn’t stray from the standard look of Hollywood biopics. The lensing by cinematographer Rachel Morrison captures the pastel colors of 1960s, as do the fashions compiled by costume designer Michael Wilkinson. But in terms of history, the film ends before the true impact of Seberg’s situation took its toll with her mysterious disappearance and “probable suicide” in 1979. Instead, Seberg ends with a note of inappropriate and baffling optimism that attempts to keep the memory of her alive. Despite an impressive ensemble and a stirring lead performance by Stewart, it’s a film that could only matter to cinephiles familiar with this obscure figure. And yet, it neither serves mainstream audiences nor those versed in Seberg’s life and legacy

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review