Searching

By Brian Eggert |

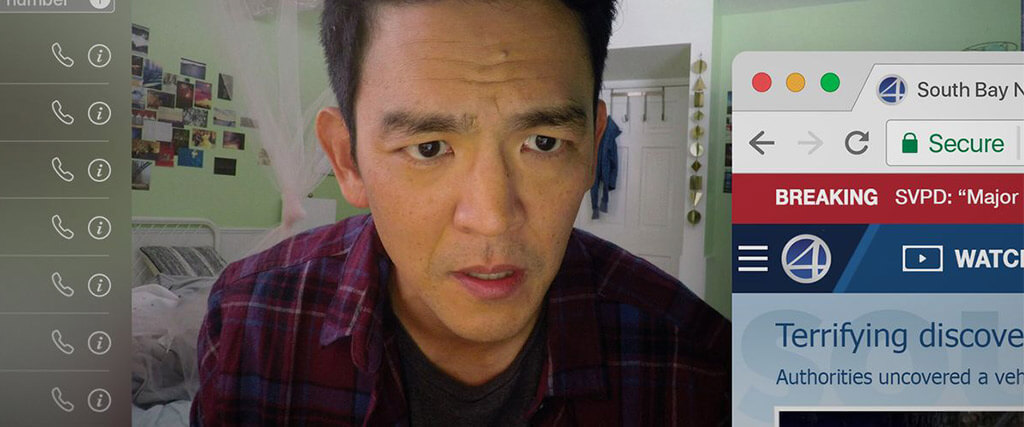

Searching assumes a first-person perspective for a cleverly conceived thriller, seen entirely on computer screens and smartphones. A missing-persons investigation unfolds on video chat and social media, with the evidence squirreled away in private files and most frequently visited sites, as a father played by John Cho attempts to locate his daughter using modern technology. Along the way, director Aneesh Chaganty’s screenplay, co-written by Sev Ohanian, reveals a timely commentary about people using social media to mask their true selves. However full of potential, the execution of the concept proves inconsistent, while the twists and turns alternate between predictable red herrings and laughably corny dialogue. What works best about Searching are not the suspense elements, but rather, the psychological puzzle that has a surprising emotional impact and a worthwhile commentary about how technology can disconnect us from real human experiences.

The opening scenes set the emotional stage. A montage unfolds on a family computer, where we glimpse home video clips that tell us the story of David (John Cho), a proud father, and Pamela (Sara Sohn), a more intimately involved mother, as they raise their daughter Margot. We see Margot grow from an infant into a teenager, played by Michelle La, experiencing the family’s warmth and togetherness. But Pamela is diagnosed with a terminal case of lymphoma, and soon David is a widower. Now six months after their wife and mother’s passing, a gulf has developed between David and Margot. Their text and FaceTime exchanges reveal a teen keeping things from her father, and a parent unable to adequately communicate with his daughter. And then one night, after missing two calls and a video chat prompt from her the night before, David realizes that Margot is missing.

David files a missing person report, and Detective Rosemary Vick (Debra Messing) takes on the case. She asks David to search Margot’s social media profiles and talk to her friends to find evidence and paint a picture of where she was before she disappeared. He’s tech-savvy enough to figure out her passwords through some amateur online sleuthing, but he’s not exactly hip to what the kids are doing these days. (“What’s a tumbler?” he asks at one point.) Nevertheless, David learns that his daughter’s life was much more complicated than he knew. Her so-called friends on Facebook are not her friends at all, while her profiles on Instagram and a live-streaming service called YouCast reveal a teen who felt sad and alone. Along with evidence provided by Det. Vick in video chats, David uncovers proof that Margot may have run away or been kidnapped. Not-so-subtle hints point David to a mysterious user named “fish_n_chips” or even his pothead brother Peter (Joseph Lee).

Only occasionally involving, Searching aims for something like Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954), where the threats seem miles away and the protagonist is helpless to stop them. The formal presentation is similar to that of Unfriended (2015) and its sequel from this year, Unfriended: Dark Web, both produced by Timur Bekmambetov, who also produced Searching. The frame is filled with David’s cursor movements and typing. But Chaganty does more than simply show the entire screen of, say, David’s laptop or smartphone. The frame provides close-ups and moves about the various screens to direct our eyes to important information. Sometimes, a search bar might fill the entire frame, or the frame itself might move from looking at one part of David’s screen to another. However, the movements are not those of David’s eyes—they’re not natural movements; they’re cinematic, but in such a way that confuses the film’s perspective. If we’re not seeing from David’s perspective, then we’re seeing from Chaganty’s.

Indeed, Chaganty seems to be driving this investigation for the audience, and his approach becomes inconsistent around midway through the proceedings. What started as a frantic web and desktop search on David’s PC, followed by Margot’s Mac, Chaganty breaks the pattern in nonsensical ways later in the film. He cuts to security cam footage from inside a prison interrogation room or live news broadcasts that show David on the scene, begging the question: Who’s watching this video feed, besides the viewer of Searching? Beyond directing our gaze without a consistent subjectivity, Chaganty also employs a tiresome score by Torin Borrowdale, which telegraphs every emotion we’re supposed to feel. The music also becomes a distraction when the suspense implied by the bombastic notes fails to match our emotional investment. Had Chaganty fully committed to the experience of web and computer searches, he would have allowed the visuals to speak for themselves and omitted the score altogether.

What works best about Searching is the emotional wallop concerning David’s discovery of Margot’s real life, and what that says about our relationship with technology. Still, for most of the 101 minutes, the film resolves to be a hackneyed and ineffective thriller. Chaganty’s unsubtle approach broadcasts every clue, relying on a tired formula where every detail onscreen proves significant in a dull way. Attentive viewers will see the twists coming. He also tells the audience what to think and feel in a bombastic way, whether it’s by the larger-than-life score or relying on sensationalistic local news broadcasters to hammer the stakes into our eyes. As a result, the film proves exaggerated and obvious, and it assumes the viewer is incapable of putting the pieces together. Rather than involving us in a mystery, it tells us the story of a mystery, which is a comparably disconnected experience. Although screened theatrically, Searching might work better on one’s laptop, where its blatant manipulation of the audience might not seem so false.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review